This repository provides the codes used to reproduce the results shown in the following paper: Generating Upper-Body Motion for Real-Time Characters Making their Way through Dynamic Environments. Eduardo Alvarado, Damien Rohmer, Marie-Paule Cani.

This system takes as input a character model, ie. a mesh geometry with a rigged skeleton being animated by an arbitrary kinematic animations (e.g., keyframed clip, MoCap data) in order to build a responsive, partial physically-based version of the input skeleton. This real-time model allows to genereate plausible upper-body interactions from single motion clips, regardless of the nature of the environment, including non-rigid obstacles such as vegetation.

In order to reproduce two-ways interactions between the upper-body and the environment, we rely on a hybrid method for character animation that couples a keyframed sequence with kinematic constraints (IK) and lightweight physics for each limb independently. The dynamic response of the character’s upper-limbs leverages antagonistic controllers, allowing us to tune tension/relaxation in the upper-body without diverging from the reference keyframe motion. A new sight model, controlled by procedural rules, enables high-level authoring of the way the character generates interactions by adapting its stiffness and reaction time. As results show, our real-time method offers precise and explicit control over the character’s behavior and style, while seamlessly adapting to new situations. Our model is therefore well suited for gaming applications.

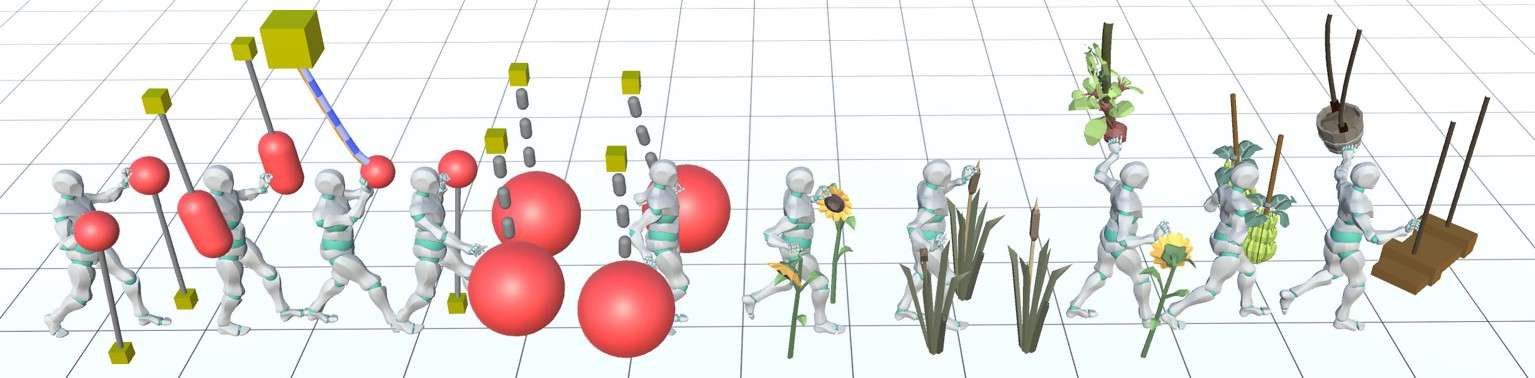

Figure 1: Examples of anticipation and two-ways interactions with different obstacles. Left: Baseline animation. Right: Ours.

We propose a hybrid character model for upper-body interactions that merges both, a kinematic input animation and lightweight physics. Our anchor system aims to blend both, in a way that is simple for the user to define which limbs are affected by physics during the animation. For example, you can decide that your torso follows the kinematic animation, while the head, or one arm, is fully driven by physics. The decision on which limbs are simulated is driven by the anchor a and remains fully dynamic, and can be activated or deactivated at run-time for each body part.

Figure 2: Different anchor configurations of our hybrid model.

Figure 3: Results of using our hybrid model on an arbitrary animation.

Then, our goal is to not only having a passive physical version of the chosen limb, but actuated based. PD controllers are able to convert an angular error to a spring-like force with certain stiffness to do this. However, setting a fixed value of tension though its gains do not allow the skeleton to reach preciselly a target orientation while external torques are applied, such as the effect of weight. On the other hand, changing the gains over time to minimize the error do also change the stiffness, and therefore the style of the motion. For this purpose, we rely on antagonistic controllers. This controllers guarantee to reach an equilibrium at any arbitrary target orientation, while preserving the motion style by decoupling stiffness and position control.

Figure 4: Actuated physical limb using antagonistric controllers. The target orientation remains unchanged while we modify the amount of muscular tension.

In a final step, we need to make the character aware of its surroundings. To leverage our antagonisic control, we now use an anticipation approach based on ray-casting and a set of procedural rules to modify the kinematic skeleton, and consequently driving the active ragdoll skeleton, resulting therefore in a responsive skeleton version of the original key-framed animation.

Figure 5: Our anticipation system detects the obstacles in front of the character and collects the metadata from the environment.

The anticipation system can be as well use to model a linear relationship between the mass information of the objects coming from the metadata of the environment and the amount of stiffness in our antagonistic control, making gestures stiffer when the character anticipates to act against heavier obstacles, or more relaxed when it acts against elements that it anticipates to be lighter. The set of procedural rules allows us to adapt the reaction time of the character too, based on the object's velocity.

Figure 6: Left: The character adapts its muscular rigidity to interact with heavier obstacles. Right: Effect of changing the reaction time.

For more information about the method and mathematical background behind the approach, please refer to the paper.

The repository contains all the necessary assets to run the project without additional material. The last version has been tested on the Unity version 2020.3.21f1. Inside the Assets, the following structure is introduced:

.

├── ...

├── Assets

│ ├── ...

│ ├── Materials # Materials used for models/grounds

│ ├── Models # Character models containing animation clips, state-machines or rigs

│ ├── Scenes # Scenes ready-to-use

│ ├── Scripts # .cs scripts for terrain deformation

│ ├── Terrain Data # Data files corresponding to terrain heightmaps

│ ├── Textures # Textures used for models/grounds

│ └── ...

├── Docs

├── ...

├── README.md

└── LICENSE

Go to Assets > Scenes and open the Terrain Deformation scene. Click in the play button, and after that, select the Game Object Terrain in the Hierarchy to trigger on the deformation system. In the Game window, you will find an environment where you can move your character, along with an interface to modify the terrain deformation parameters.

Figure 3: Demo interface for terrain deformation.

In order to start deforming the terrain while you move, make sure that the option Deformation in the upper-left corner is active. If you want to activate the lateral dispacement, select the opcion Bump. To activate the post-processing step using Gaussian Blur, activate Post-processing. The options are:

- Terrain Options:

- Young's Modulus E: Defines the elastic constant of the terrain, measured in [Pa]. It has a direct impact on the terrain compressibility. Smaller values lead to more compressible terrains, and therefore deeper deformations.

- Contact Time τ: Defines the characteristic time of the terrain, measure in [s]. It is the time needed for the character to be fully stopped by a given type of terrain, during which the ground exerts a reaction force. Larger values lead to smaller force values during a larger period of time, while smaller values lead to stronger reaction forces during a short period of time.

- Poisson Ratio ν: Defines the amount of volume preserved at the end of the deformation, and is adimensional. An ideal incompressible material has a Poisson ratio of 0.5. This will cause a larger bump while the option is active, as the volume during the deformation is totally preserved. As the value of ν gets smaller, the material compresses and the amount of volume displaced on the outline of the footprint will be lower.

- Gaussian Iteratons: Number of iterations for the Gaussian Blur filter. Larger values lead to smoother footprint results.

- Show:

- Raycast Grid: Displays raycast method to estimate the contact area between the ground and the feet.

- Bump: Displays contour of the footprint.

- Wireframe: Switches to wireframe mode to show the 3D terrain mesh and the deformations.

- Forces: Displays force model from the kinematic animation in real-time.

- Forces: Prints the values for weight, momentum forces and ground reaction forces per foot. Measured in [N].

- Deformation: Prints the values for the feet positions, number of ray hits used to calculate the contact area, pressure per foot measured in [N/m²] and compressive displacement per foot measured in [mm].

In order to reset the terrain, just select Terrain in the Hierarchy and use the Set Height brush in the Terrain Component in the Inspector. Then, set the Height value to 1 and paint the terrain to reset it (while the application is not playing).

In the folder Scenes, you can find the scene Terrain Deformation - Showcases. This scene contains three types of grounds (snow, sand and mud), defined by different parametrization. When the character moves though these terrains, the system will switch automatically based on the material where the character is stepping in, changing the deformation appearance.

For more information about the values for each type of material, please refer to the paper.

@article{10.3389/frvir.2022.801856,

title = {Real-Time Locomotion on Soft Grounds With Dynamic Footprints},

author = {Alvarado, Eduardo and Paliard, Chloé and Rohmer, Damien and Cani, Marie-Paule},

doi = {10.3389/FRVIR.2022.801856},

journal = {Frontiers in Virtual Reality},

volume = {3},

pages = {3},

year = {2022},

month = {mar},

copyright = {All rights reserved},

issn = {2673-4192},

url = {https://hal.inria.fr/hal-03630136},

urldate = {2022-04-05}

}The code is released under MIT License. See LICENSE for details.