Popular operating systems allow isolating different programs by executing them in separate processes. A :term:`socket` is a tool provided by the operating system that enables two separated processes to communicate with each other. A socket takes the form of a file descriptor and can be seen as a communication pipe through which the communicating processes can exchange arbitrary information. In order to receive a message, a process must be attached to a specific :term:`address` that the peer can use to reach it.

.. tikz:: Connecting two processes communicating on the same computer

:libs: calc

% processes

\begin{scope}[local bounding box=processes]

% process A

\draw (1,1) rectangle (3.5,4) node[midway] {\texttt{Process A}};

% process B

\draw (10,1) rectangle (12.5,4) node[midway] {\texttt{Process B}};

\draw[fill=gray] (3.25, 1.75) rectangle (3.75, 3.25) node[midway, rotate=90] {socket}; % socket 1

\draw[fill=gray] (9.75, 1.75) rectangle (10.25, 3.25) node[midway, rotate=270] {socket}; % socket 2

% pipe 1

\draw (3.75, 2) -- (9.75, 2);

\draw (3.75, 2.15) -- (9.75, 2.15);

% arrow of pipe 1

\draw[->, thick] (6, 1.8) -- (7.5, 1.8);

% pipe 2

\draw (3.75, 3) -- (9.75, 3);

\draw (3.75, 2.85) -- (9.75, 2.85);

% arrow of pipe 2

\draw[<-, thick] (6, 3.2) -- (7.5, 3.2);

\end{scope}

\draw (0,0) rectangle (13.5, 5) node[midway] {};

\node[anchor=south west] at (0.1, 0.1) {\texttt{Computer 1}};

\draw ($(processes.south west) + (-1,-1)$) rectangle ($(processes.north east) + (1,1)$);

The socket is a powerful abstraction as it allows processes to communicate even if they are located on different computers. In this specific cases, the inter-processes communication will go through a network.

.. tikz:: Connecting two processes communicating on different computers

:libs: calc

% processes

\begin{scope}[local bounding box=processes]

% process A

\draw (1,1) rectangle (3.5,4) node[midway] {\texttt{Process A}};

% process B

\draw (10,1) rectangle (12.5,4) node[midway] {\texttt{Process B}};

\draw[fill=gray] (3.25, 1.75) rectangle (3.75, 3.25) node[midway, rotate=90] {socket}; % socket 1

\draw[fill=gray] (9.75, 1.75) rectangle (10.25, 3.25) node[midway, rotate=270] {socket}; % socket 2

% pipe 1

\draw (3.75, 2) -- (9.75, 2);

\draw (3.75, 2.15) -- (9.75, 2.15);

% arrow of pipe 1

\draw[->, thick] (6, 1.8) -- (7.5, 1.8);

% pipe 2

\draw (3.75, 3) -- (9.75, 3);

\draw (3.75, 2.85) -- (9.75, 2.85);

% arrow of pipe 2

\draw[<-, thick] (6, 3.2) -- (7.5, 3.2);

\end{scope}

% computer 1

\draw (0,0) rectangle (4.5, 5) node[midway] {};

\node[anchor=south west] at (0.1, 0.1) {\texttt{Computer 1}};

% computer 2

\draw (9,0) rectangle (13.5, 5) node[midway] {};

\node[anchor=south east] at (13.4, 0.1) {\texttt{Computer 2}};

Networked applications were usually implemented by using the :term:`socket` :term:`API`. This API was designed when TCP/IP was first implemented in the `Unix BSD`_ operating system [Sechrest]_ [LFJLMT]_, and has served as the model for many APIs between applications and the networking stack in an operating system. Although the socket API is very popular, other APIs have also been developed. For example, the STREAMS API has been added to several Unix System V variants [Rago1993]_. The socket API is supported by most programming languages and several textbooks have been devoted to it. Users of the C language can consult [DC2009]_, [Stevens1998]_, [SFR2004]_ or [Kerrisk2010]_. The Java implementation of the socket API is described in [CD2008]_ and in the Java tutorial. In this section, we will use the C socket API to illustrate the key concepts.

The socket API is quite low-level and should be used only when you need a complete control of the network access. If your application simply needs, for instance, to retrieve data from a web server, there are much simpler and higher-level APIs.

A detailed discussion of the socket API is outside the scope of this section and the references cited above provide a detailed discussion of all the details of the socket API. As a starting point, it is interesting to compare the socket API with the service primitives that we have discussed in the previous chapter. Let us first consider the connectionless service that consists of the following two primitives :

- DATA.request(destination,message) is used to send a message to a specified destination. In this socket API, this corresponds to the

sendmethod.- DATA.indication(message) is issued by the transport service to deliver a message to the application. In the socket API, this corresponds to the return of the

recvmethod that is called by the application.

The DATA primitives are exchanged through a service access point. In the socket API, the equivalent to the service access point is the socket. A socket is a data structure which is maintained by the networking stack and is used by the application every time it needs to send or receive data through the networking stack.

In order to reach a peer, a process must know its :term:`address`. An address is a value that identifies a peer in a given network. There exists many different kinds of address families. For example, some of them allow reaching a peer using the file system on the computer. Some others enable communicating with a remote peer through a network. The socket API provides generic functions: the peer address is taken as a struct sockaddr *, which can point to any family of address. This is partly why sockets are a powerful abstraction.

The sendto system call allows to send data to a peer identified by its socket address through a given socket.

ssize_t sendto(int sockfd, const void *buf, size_t len, int flags, const struct sockaddr *dest_addr, socklen_t addrlen);The first argument is the file descriptor of the socket that we use to perform the communication. buf is a buffer of length len containing the bytes to send to the peer. The usage of flags argument is out of the scope of this section and can be set to 0. dest_addr is the socket address of the destination to which we want to send the bytes, its length is passed using the addrlen argument.

In the following example, a C program is sending the bytes 'h', 'e', 'l', 'l' and 'o' to a remote process located at address peer_addr, using the already created socket sock.

int send_hello_to_peer(int sock, struct sockaddr *peer_addr, size_t peer_addr_len) {

ssize_t sent = sendto(sock, "hello", strlen("hello"), 0, peer_addr, peer_addr_len);

if (sent == -1) {

printf("could not send the message, error: %s\n", strerror(errno));

return errno;

}

return 0;

}As the sendto function is generic, this function will work correctly independently from the fact that the peer's address is defined as a path on the computer filesystem or a network address.

Operating systems allow assigning an address to a socket using the bind system call. This is useful when you want to receive messages from another program to which you announced your socket address.

Once the address is assigned to the socket, the program can receive data from others using system calls such as recv and read. Note that we can use the read system call as the operating system provides a socket as a file descriptor.

The following program binds its socket to a given socket address and then waits for receiving new bytes, using the already created socket sock.

#define MAX_MESSAGE_SIZE 2500

int bind_and_receive_from_peer(int sock, struct sockaddr *local_addr, socklen_t local_addr_len) {

int err = bind(sock, local_addr, local_addr_len); // assign our address to the socket

if (err == -1) {

printf("could not bind on the socket, error: %s\n", strerror(errno));

return errno;

}

char buffer[MAX_MESSAGE_SIZE]; // allocate a buffer of MAX_MESSAGE_SIZE bytes on the stack

ssize_t n_received = recv(sock, buffer, MAX_MESSAGE_SIZE, 0); // equivalent to do: read(sock, buffer, MAX_MESSAGE_SIZE);

if (n_received == -1) {

printf("could not receive the message, error: %s\n", strerror(errno));

return errno;

}

// let's print what we received !

printf("received %ld bytes:\n", n_received);

for (int i = 0 ; i < n_received ; i++) {

printf("0x%hhx ('%c') ", buffer[i], buffer[i]);

}

printf("\n");

return 0;

}Note

Depending on the socket address family, the operating system might implicitly assign an address to an unbound socket upon a call to write, send or sendto. While this is a useful behavior, describing it precisely is out of the scope of this section.

Warning

While the provided examples show the usage of a char array as the data buffer, implementers should never assume that it contains a string. C programs rely on the char type to refer to a 8-bit long value, and arbitrary binary values can be exchanged over the network (i.e., the \0 value does not delimit the end of the data).

Using this code, the program will read and print an arbitrary message received from an arbitrary peer who knows the program's socket address. If we want to know the address of the peer that sent us the message, we can use the recvfrom system call. This is what a modified version of bind_and_receive_from_peer is doing below.

#define MAX_MESSAGE_SIZE 2500

int bind_and_receive_from_peer_with_addr(int sock) {

int err = bind(sock, local_addr, local_addr_len); // assign our address to the socket

if (err == -1) {

printf("could not bind on the socket, error: %s\n", strerror(errno));

return errno;

}

struct sockaddr_storage peer_addr; // allocate the peer's address on the stack. It will be initialized when we receive a message

socklen_t peer_addr_len = sizeof(struct sockaddr_storage); // variable that will contain the length of the peer's address

char buffer[MAX_MESSAGE_SIZE]; // allocate a buffer of MAX_MESSAGE_SIZE bytes on the stack

ssize_t n_received = recvfrom(sock, buffer, MAX_MESSAGE_SIZE, 0, (struct sockaddr *) &peer_addr, &peer_addr_len);

if (n_received == -1) {

printf("could not receive the message, error: %s\n", strerror(errno));

return errno;

}

// let's print what we received !

printf("received %ld bytes:\n", n_received);

for (int i = 0 ; i < n_received ; i++) {

printf("0x%hhx ('%c') ", buffer[i], buffer[i]);

}

printf("\n");

// let's now print the address of the peer

uint8_t *peer_addr_bytes = (uint8_t *) &peer_addr;

printf("the socket address of the peer is (%ld bytes):\n", peer_addr_len);

for (int i = 0 ; i < peer_addr_len ; i++) {

printf("0x%hhx ", peer_addr_bytes[i]);

}

printf("\n");

return 0;

}This function is now using the recvfrom system call that will also provide the address of the peer who sent the message. As addresses are generic and can have different sizes, recvfrom also tells us the size of the address that it has written.

Operating systems enable linking a socket to a remote address so that every information sent through the socket will only be sent to this remote address, and the socket will only receive messages sent by this remote address. This can be done using the connect system call shown below.

int connect(int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen);This system call will assign the socket sockfd to the addr remote socket address. The process can then use the send and write system calls that do not to specify the destination socket address.

Furthermore, the calls to recv and read will only deliver messages sent by this remote address. This is useful when we only care about the other peer messages.

The following program connects a socket to a remote address, sends a message and waits for a reply.

#define MAX_MESSAGE_SIZE 2500

int send_hello_to_and_read_reply_from_connected_peer(int sock, struct sockaddr *peer_addr, size_t peer_addr_len) {

int err = connect(sock, peer_addr, peer_addr_len); // connect the socket to the peer

if (err == -1) {

printf("cound not connect the socket: %s\n", strerror(errno));

return errno;

}

ssize_t written = write(sock, "hello", strlen("hello")); // we can use the generic write(2) system call: we do not need to specify the destination socket address

if (written == -1) {

printf("could not send the message, error: %s\n", strerror(errno));

return errno;

}

uint8_t buffer[MAX_MESSAGE_SIZE]; // allocate the receive buffer on the stack

ssize_t amount_read = read(sock, buffer, MAX_MESSAGE_SIZE);

if (amount_read == -1) {

printf("could not read on the socket, error: %s\n", strerror(errno));

return errno;

}

// let's print what we received !

printf("received %ld bytes:\n", amount_read);

for (int i = 0 ; i < amount_read ; i++) {

printf("0x%hhx ('%c') ", buffer[i], buffer[i]);

}

return 0;

}Until now, we learned how to use sockets that were already created. When writing a whole program, you will have to create you own sockets and choose the concrete technology that it will use to communicate with others. In this section, we will create new sockets and allow a program to communicate with processes located on another computer using a network. The most recent standardized technology used to communicate through a network is the :term:`IPv6` network protocol. In the IPv6 protocol, hosts are identified using IPv6 addresses. Modern operating systems allow IPv6 network communications between programs to be done using the socket API, just as we did in the previous sections.

A program can use the socket system call to create a new socket.

int socket(int domain, int type, int protocol)The domain parameter specifies the address family that we will use to concretely perform the communication. For an IPv6 socket, the domain parameter will be set to the value AF_INET6, telling the operating system that we plan to communicate using IPv6 addresses.

The type parameter specifies the communication guarantees that we need. For now, we will use the type SOCK_DGRAM which allows us to send unreliable messages. This means that each data that we send at each call of sendto will either be completely received or not received at all. The last parameter will be set to 0. The following line creates a socket, telling the operating system that we want to communicate using IPv6 addresses and that we want to send unreliable messages.

int sock = socket(AF_INET6, SOCK_DGRAM, 0);- Now that we created an IPv6 socket, we can use it to reach another program if we know its IPv6 address. IPv6 addresses have a human-readable format that can be represented as a string of characters. The details of IPv6 addresses are out of scope of this section but here are some examples :

- The

::1IPv6 address identifies the computer on which the current program is running. - The

2001:6a8:308f:9:0:82ff:fe68:e520IPv6 address identifies the computer serving thehttps://beta.computer-networking.infowebsite.

- The

- An IPv6 address often identifies a computer and not a program running on the computer. In order to identify a specific program running on a specific computer, we use a port number in addition to the IPv6 address. A program using an IPv6 socket is this identified using :

- The IPv6 address of the computer

- The port number identifying the program running on the computer

A program can use the struct sockaddr_in6 to represent IPv6 socket addresses. The following program creates a struct sockaddr_in6 that identifies the program that reserved the port number 55555 on the computer identified by the ::1 IPv6 address.

struct sockaddr_in6 peer_addr; // allocate the address on the stack

memset(&peer_addr, 0, sizeof(peer_addr)); // fill the address with 0-bytes to avoid garbage-values

peer_addr.sin6_family = AF_INET6; // indicate that the address is an IPv6 address

peer_addr.sin6_port = htons(55555); // indicate that the programm is running on port 55555

inet_pton(AF_INET6, "::1", &peer_addr.sin6_addr); // indicate that the program is running on the computer identified by the ::1 IPv6 addressNow, we have built everything we need to send a message to the remote program. The create_socket_and_send_message function below assembles all the building blocks we created until now in order to send the message "hello" to the program running on port 55555 on the computer identified by the ::1 IPv6 address.

int create_socket_and_send_message() {

int sock = socket(AF_INET6, SOCK_DGRAM, 0); // create a socket using IPv6 addresses

if (sock == -1) {

printf("could not create the IPv6 SOCK_DGRAM socket, error: %s\n", strerror(errno));

return errno;

}

struct sockaddr_in6 peer_addr; // allocate the address on the stack

memset(&peer_addr, 0, sizeof(peer_addr)); // fill the address with 0-bytes to avoid garbage-values

peer_addr.sin6_family = AF_INET6; // indicate that the address is an IPv6 address

peer_addr.sin6_port = htons(55555); // indicate that the programm is running on port 55555

inet_pton(AF_INET6, "::1", &peer_addr.sin6_addr); // indicate that the program is running on the computer identified by the ::1 IPv6 address

send_hello_to_peer(sock, (struct sockaddr *) &peer_addr, sizeof(peer_addr)); // use the send_hello_to_peer function that we defined previously

close(sock); // release the resources used by the socket

return 0;

}Note that we can reuse our send_hello_to_peer function without any modification as we wrote it to handle any kind of sockets, including sockets using the IPv6 network protocol.

Besides character strings, some applications also need to exchange 16 bits and 32 bits fields such as integers. A naive solution would have been to send the 16- or 32-bits field as it is encoded in the host's memory. Unfortunately, there are different methods to store 16- or 32-bits fields in memory. Some CPUs store the most significant byte of a 16-bits field in the first address of the field while others store the least significant byte at this location. When networked applications running on different CPUs exchange 16 bits fields, there are two possibilities to transfer them over the transport service :

- send the most significant byte followed by the least significant byte

- send the least significant byte followed by the most significant byte

The first possibility was named big-endian in a note written by Cohen [Cohen1980]_ while the second was named little-endian. Vendors of CPUs that used big-endian in memory insisted on using big-endian encoding in networked applications while vendors of CPUs that used little-endian recommended the opposite. Several studies were written on the relative merits of each type of encoding, but the discussion became almost a religious issue [Cohen1980]_. Eventually, the Internet chose the big-endian encoding, i.e. multi-byte fields are always transmitted by sending the most significant byte first, RFC 791 refers to this encoding as the :term:`network-byte order`. Most libraries [1] used to write networked applications contain functions to convert multi-byte fields from memory to the network byte order and the reverse.

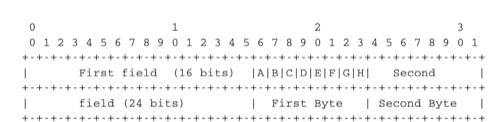

Besides 16 and 32 bit words, some applications need to exchange data structures containing bit fields of various lengths. For example, a message may be composed of a 16 bits field followed by eight, one bit flags, a 24 bits field and two 8 bits bytes. Internet protocol specifications will define such a message by using a representation such as the one below. In this representation, each line corresponds to 32 bits and the vertical lines are used to delineate fields. The numbers above the lines indicate the bit positions in the 32-bits word, with the high order bit at position 0.

The message mentioned above will be transmitted starting from the upper 32-bits word in network byte order. The first field is encoded in 16 bits. It is followed by eight one bit flags (A-H), a 24 bits field whose high order byte is shown in the first line and the two low order bytes appear in the second line followed by two one byte fields. This ASCII representation is frequently used when defining binary protocols. We will use it for all the binary protocols that are discussed in this book.

Here are some exercises that will help you to learn how to use sockets.

.. inginious:: sockets-creating-a-socket

.. inginious:: sockets-creating-a-listening-socket

.. inginious:: sockets-sending-strings

.. inginious:: sockets-client-application

.. inginious:: sockets-server-application

During this course, you will be asked to implement a transport protocol running on Linux devices. To prepare yourself, try to implement the protocol described in the above tasks on your Linux personal machine. If you did these exercises correctly, most of your answers can be used as it (do not forget to include the required header files). In addition to the previously produced code, you will need

- to wrap the

create_and_send_messagein aclientexecutable that can parse user arguments (thegetopt(3)function might help) and appropriately call the wrapped function;- to wrap the

recv_and_handle_messageserver function in aserverexecutable, similarly to what you have done with theclientexecutable.

As an example, here is what you could have to invoke your programs.

# Let put the server on port 10000 (small port numbers are priviledged) and run it as a daemon)

$ ./server :: 10000 &

# Let us call the client and request an addition result, as an int

$ ./client -op + ::1 10000 1 3 5 7 9

Result: 25

# Request now a multiplication, but returned as a string

$ ./client -op * -s ::1 10000 1 3 5 7 9

Result: 945If you want to observe the packets exchanged over the network, use a packet dissector such as `wireshark`_ or `tcpdump`_, listen the loopback interface (lo) and filter UDP packets using port 10000 (udp.port==10000 in `wireshark`_, udp port 10000 with `tcpdump`_).

Footnotes

| [1] | For example, the htonl(3) (resp. ntohl(3)) function the standard C library converts a 32-bits unsigned integer from the byte order used by the CPU to the network byte order (resp. from the network byte order to the CPU byte order). Similar functions exist in other programming languages. |