The moment-to-moment health of the XRP Ledger network depends on the health and connectivity of a small number of computers (nodes). The most important nodes are validators, specifically ones listed on the unique node list (UNL). Ripple publishes a recommended UNL that most network nodes use to determine which peers in the network are trusted. Although most validators use the same list, they are not required to. The XRP Ledger network progresses to the next ledger when enough validators reach agreement (above the minimum quorum of 80%) about what transactions to include in the next ledger.

As an example, if there are 10 validators on the UNL, at least 8 validators have to agree with the latest ledger for it to become validated. But what if enough of those validators are offline to drop the network below the 80% quorum? The XRP Ledger network favors safety/correctness over advancing the ledger. Which means if enough validators are offline, the network will not be able to validate ledgers.

Unfortunately validators can go offline at any time for many different reasons. Power outages, network connectivity issues, and hardware failures are just a few scenarios where a validator would appear "offline". Given that most of these events are temporary, it would make sense to temporarily remove that validator from the UNL. But the UNL is updated infrequently and not every node uses the same UNL. So instead of removing the unreliable validator from the Ripple recommended UNL, we can create a second negative UNL which is stored directly on the ledger (so the entire network has the same view). This will help the network see which validators are currently unreliable, and adjust their quorum calculation accordingly.

Improving the liveness of the network is the main motivation for the negative UNL.

In order to determine which validators are unreliable, we need clearly define what kind of faults to measure and analyze. We want to deal with the faults we frequently observe in the production network. Hence we will only monitor for validators that do not reliably respond to network messages or send out validations disagreeing with the locally generated validations. We will not target other byzantine faults.

To track whether or not a validator is responding to the network, we could monitor them with a “heartbeat” protocol. Instead of creating a new heartbeat protocol, we can leverage some existing protocol messages to mimic the heartbeat. We picked validation messages because validators should send one and only one validation message per ledger. In addition, we only count the validation messages that agree with the local node's validations.

With the negative UNL, the network could keep making forward progress safely even if the number of remaining validators gets to 60%. Say we have a network with 10 validators on the UNL and everything is operating correctly. The quorum required for this network would be 8 (80% of 10). When validators fail, the quorum required would be as low as 6 (60% of 10), which is the absolute minimum quorum. We need the absolute minimum quorum to be strictly greater than 50% of the original UNL so that there cannot be two partitions of well-behaved nodes headed in different directions. We arbitrarily choose 60% as the minimum quorum to give a margin of safety.

Consider these events in the absence of negative UNL:

- 1:00pm - validator1 fails, votes vs. quorum: 9 >= 8, we have quorum

- 3:00pm - validator2 fails, votes vs. quorum: 8 >= 8, we have quorum

- 5:00pm - validator3 fails, votes vs. quorum: 7 < 8, we don’t have quorum

- network cannot validate new ledgers with 3 failed validators

We're below 80% agreement, so new ledgers cannot be validated. This is how the XRP Ledger operates today, but if the negative UNL was enabled, the events would happen as follows. (Please note that the events below are from a simplified version of our protocol.)

- 1:00pm - validator1 fails, votes vs. quorum: 9 >= 8, we have quorum

- 1:40pm - network adds validator1 to negative UNL, quorum changes to ceil(9 * 0.8), or 8

- 3:00pm - validator2 fails, votes vs. quorum: 8 >= 8, we have quorum

- 3:40pm - network adds validator2 to negative UNL, quorum changes to ceil(8 * 0.8), or 7

- 5:00pm - validator3 fails, votes vs. quorum: 7 >= 7, we have quorum

- 5:40pm - network adds validator3 to negative UNL, quorum changes to ceil(7 * 0.8), or 6

- 7:00pm - validator4 fails, votes vs. quorum: 6 >= 6, we have quorum

- network can still validate new ledgers with 4 failed validators

This proposal will:

- add a new pseudo-transaction type

- add the negative UNL to the ledger data structure.

Any tools or systems that rely on the format of this data will have to be updated.

This feature will need an amendment to activate.

This section discusses the following topics about the Negative UNL design:

- Negative UNL protocol overview

- Validator reliability measurement

- Format Changes

- Negative UNL maintenance

- Quorum size calculation

- Filter validation messages

- High level sequence diagram of code changes

Every ledger stores a list of zero or more unreliable validators. Updates to the list must be approved by the validators using the consensus mechanism that validators use to agree on the set of transactions. The list is used only when checking if a ledger is fully validated. If a validator V is in the list, nodes with V in their UNL adjust the quorum and V’s validation message is not counted when verifying if a ledger is fully validated. V’s flow of messages and network interactions, however, will remain the same.

We define the effective UNL = original UNL - negative UNL, and the effective quorum as the quorum of the effective UNL. And we set effective quorum = Ceiling(80% * effective UNL).

A node only measures the reliability of validators on its own UNL, and only proposes based on local observations. There are many metrics that a node can measure about its validators, but we have chosen ledger validation messages. This is because every validator shall send one and only one signed validation message per ledger. This keeps the measurement simple and removes timing/clock-sync issues. A node will measure the percentage of agreeing validation messages (PAV) received from each validator on the node's UNL. Note that the node will only count the validation messages that agree with its own validations.

We define the PAV as the Percentage of Agreed Validation messages received for the last N ledgers, where N = 256 by default.

When the PAV drops below the low-water mark, the validator is considered unreliable, and is a candidate to be disabled by being added to the negative UNL. A validator must have a PAV higher than the high-water mark to be re-enabled. The validator is re-enabled by removing it from the negative UNL. In the implementation, we plan to set the low-water mark as 50% and the high-water mark as 80%.

The negative UNL component in a ledger contains three fields.

- NegativeUNL: The current negative UNL, a list of unreliable validators.

- ToDisable: The validator to be added to the negative UNL on the next flag ledger.

- ToReEnable: The validator to be removed from the negative UNL on the next flag ledger.

All three fields are optional. When the ToReEnable field exists, the NegativeUNL field cannot be empty.

A new pseudo-transaction, UNLModify, is added. It has three fields

- Disabling: A flag indicating whether the modification is to disable or to re-enable a validator.

- Seq: The ledger sequence number.

- Validator: The validator to be disabled or re-enabled.

There would be at most one disable UNLModify and one re-enable UNLModify

transaction per flag ledger. The full machinery is described further on.

The negative UNL can only be modified on the flag ledgers. If a validator's reliability status changes, it takes two flag ledgers to modify the negative UNL. Let's see an example of the algorithm:

- Ledger seq = 100: A validator V goes offline.

- Ledger seq = 256: This is a flag ledger, and V's reliability measurement PAV

is lower than the low-water mark. Other validators add

UNLModifypseudo-transactions{true, 256, V}to the transaction set which goes through the consensus. Then the pseudo-transaction is applied to the negative UNL ledger component by settingToDisable = V. - Ledger seq = 257 ~ 511: The negative UNL ledger component is copied from the parent ledger.

- Ledger seq=512: This is a flag ledger, and the negative UNL is updated

NegativeUNL = NegativeUNL + ToDisable.

The negative UNL may have up to MaxNegativeListed = floor(original UNL * 25%)

validators. The 25% is because of 75% * 80% = 60%, where 75% = 100% - 25%, 80%

is the quorum of the effective UNL, and 60% is the absolute minimum quorum of

the original UNL. Adding more than 25% validators to the negative UNL does not

improve the liveness of the network, because adding more validators to the

negative UNL cannot lower the effective quorum.

The following is the detailed algorithm:

-

If the ledger seq = x is a flag ledger

-

Compute

NegativeUNL = NegativeUNL + ToDisable - ToReEnableif they exist in the parent ledger-

Try to find a candidate to disable if

sizeof NegativeUNL < MaxNegativeListed -

Find a validator V that has a PAV lower than the low-water mark, but is not in

NegativeUNL. -

If two or more are found, their public keys are XORed with the hash of the parent ledger and the one with the lowest XOR result is chosen.

-

If V is found, create a

UNLModifypseudo-transactionTxDisableValidator = {true, x, V}

-

-

Try to find a candidate to re-enable if

sizeof NegativeUNL > 0:-

Find a validator U that is in

NegativeUNLand has a PAV higher than the high-water mark. -

If U is not found, try to find one in

NegativeUNLbut not in the local UNL. -

If two or more are found, their public keys are XORed with the hash of the parent ledger and the one with the lowest XOR result is chosen.

-

If U is found, create a

UNLModifypseudo-transactionTxReEnableValidator = {false, x, U}

-

-

If any

UNLModifypseudo-transactions are created, add them to the transaction set. The transaction set goes through the consensus algorithm. -

If have enough support, the

UNLModifypseudo-transactions remain in the transaction set agreed by the validators. Then the pseudo-transactions are applied to the ledger:-

If have

TxDisableValidator, setToDisable=TxDisableValidator.V. Else clearToDisable. -

If have

TxReEnableValidator, setToReEnable=TxReEnableValidator.U. Else clearToReEnable.

-

-

-

Else (not a flag ledger)

- Copy the negative UNL ledger component from the parent ledger

The negative UNL is stored on each ledger because we don't know when a validator may reconnect to the network. If the negative UNL was stored only on every flag ledger, then a new validator would have to wait until it acquires the latest flag ledger to know the negative UNL. So any new ledgers created that are not flag ledgers copy the negative UNL from the parent ledger.

Note that when we have a validator to disable and a validator to re-enable at

the same flag ledger, we create two separate UNLModify pseudo-transactions. We

want either one or the other or both to make it into the ledger on their own

merits.

Readers may have noticed that we defined several rules of creating the

UNLModify pseudo-transactions but did not describe how to enforce the rules.

The rules are actually enforced by the existing consensus algorithm. Unless

enough validators propose the same pseudo-transaction it will not be included in

the transaction set of the ledger.

The effective quorum is 80% of the effective UNL. Note that because at most 25%

of the original UNL can be on the negative UNL, the quorum should not be lower

than the absolute minimum quorum (i.e. 60%) of the original UNL. However,

considering that different nodes may have different UNLs, to be safe we compute

quorum = Ceiling(max(60% * original UNL, 80% * effective UNL)).

If a validator V is in the negative UNL, it still participates in consensus sessions in the same way, i.e. V still follows the protocol and publishes proposal and validation messages. The messages from V are still stored the same way by everyone, used to calculate the new PAV for V, and could be used in future consensus sessions if needed. However V's ledger validation message is not counted when checking if the ledger is fully validated.

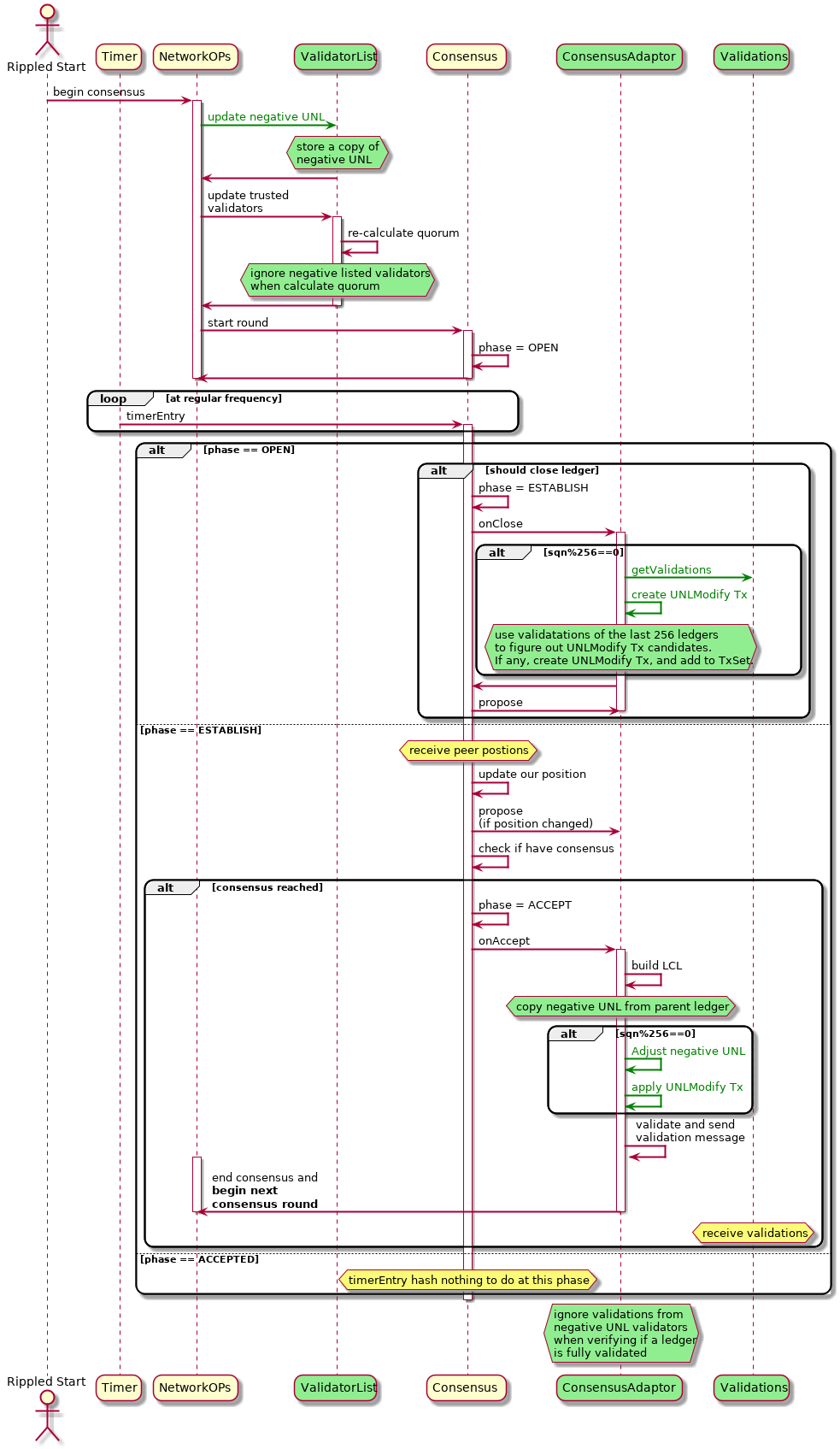

The diagram below is the sequence of one round of consensus. Classes and components with non-trivial changes are colored green.

-

The

ValidatorListclass is modified to compute the quorum of the effective UNL. -

The

Validationsclass provides an interface for querying the validation messages from trusted validators. -

The

ConsensusAdaptorcomponent:-

The

RCLConsensus::Adaptorclass is modified for creatingUNLModifyPseudo-Transactions. -

The

Changeclass is modified for applyingUNLModifyPseudo-Transactions. -

The

Ledgerclass is modified for creating and adjusting the negative UNL ledger component. -

The

LedgerMasterclass is modified for filtering out validation messages from negative UNL validators when verifying if a ledger is fully validated.

-

The previous version of the negative UNL specification used the same mechanism as the fee voting for creating the negative UNL, and used the negative UNL as soon as the ledger was fully validated. However the timing of fully validation can differ among nodes, so different negative UNLs could be used, resulting in different effective UNLs and different quorums for the same ledger. As a result, the network's safety is impacted.

This updated version does not impact safety though operates a bit more slowly. The negative UNL modifications in the UNLModify pseudo-transaction approved by the consensus will take effect at the next flag ledger. The extra time of the 256 ledgers should be enough for nodes to be in sync of the negative UNL modifications.

After a validator disabled by the negative UNL becomes reliable, other validators explicitly vote for re-enabling it. An alternative approach to re-enable a validator is the expiration approach, which was considered in the previous version of the specification. In the expiration approach, every entry in the negative UNL has a fixed expiration time. One flag ledger interval was chosen as the expiration interval. Once expired, the other validators must continue voting to keep the unreliable validator on the negative UNL. The advantage of this approach is its simplicity. But it has a requirement. The negative UNL protocol must be able to vote multiple unreliable validators to be disabled at the same flag ledger. In this version of the specification, however, only one unreliable validator can be disabled at a flag ledger. So the expiration approach cannot be simply applied.

If the ledger time is about 4.5 seconds and the low-water mark is 50%, then in the worst case, it takes 48 minutes ((0.5 * 256 + 256 + 256) * 4.5 / 60 = 48) to put an offline validator on the negative UNL. We considered lowering the flag ledger frequency so that the negative UNL can be more responsive. We also considered decoupling the reliability measurement and flag ledger frequency to be more flexible. In practice, however, their benefits are not clear.

A group of malicious validators may try to frame a reliable validator and put it on the negative UNL. But they cannot succeed. Because:

-

A reliable validator sends a signed validation message every ledger. A sufficient peer-to-peer network will propagate the validation messages to other validators. The validators will decide if another validator is reliable or not only by its local observation of the validation messages received. So an honest validator’s vote on another validator’s reliability is accurate.

-

Given the votes are accurate, and one vote per validator, an honest validator will not create a UNLModify transaction of a reliable validator.

-

A validator can be added to a negative UNL only through a UNLModify transaction.

Assuming the group of malicious validators is less than the quorum, they cannot frame a reliable validator.

The bullet points below briefly summarize the current proposal:

-

The motivation of the negative UNL is to improve the liveness of the network.

-

The targeted faults are the ones frequently observed in the production network.

-

Validators propose negative UNL candidates based on their local measurements.

-

The absolute minimum quorum is 60% of the original UNL.

-

The format of the ledger is changed, and a new UNLModify pseudo-transaction is added. Any tools or systems that rely on the format of these data will have to be updated.

-

The negative UNL can only be modified on the flag ledgers.

-

At most one validator can be added to the negative UNL at a flag ledger.

-

At most one validator can be removed from the negative UNL at a flag ledger.

-

If a validator's reliability status changes, it takes two flag ledgers to modify the negative UNL.

-

The quorum is the larger of 80% of the effective UNL and 60% of the original UNL.

-

If a validator is on the negative UNL, its validation messages are ignored when the local node verifies if a ledger is fully validated.

Quote from the Technical FAQ: "They are the lists of transaction validators a given participant believes will not conspire to defraud them."

The network can make forward progress when more than a quorum of the trusted validators agree with the progress. The lower the quorum size is, the easier for the network to progress. If the quorum is too low, however, the network is not safe because nodes may have different results. So the quorum size used in the consensus protocol is a balance between the safety and the liveness of the network. The negative UNL reduces the size of the effective UNL, resulting in a lower quorum size while keeping the network safe.

Question: How does a validator get into the negative UNL? How is a validator removed from the negative UNL?

A validator’s reliability is measured by other validators. If a validator becomes unreliable, at a flag ledger, other validators propose UNLModify pseudo-transactions which vote the validator to add to the negative UNL during the consensus session. If agreed, the validator is added to the negative UNL at the next flag ledger. The mechanism of removing a validator from the negative UNL is the same.

Answer: Let’s consider the cases:

-

A validator is added to the UNL, and it is already in the negative UNL. This case could happen when not all the nodes have the same UNL. Note that the negative UNL on the ledger lists unreliable nodes that are not necessarily the validators for everyone.

In this case, the liveness is affected negatively. Because the minimum quorum could be larger but the usable validators are not increased.

-

A validator is removed from the UNL, and it is in the negative UNL.

In this case, the liveness is affected positively. Because the quorum could be smaller but the usable validators are not reduced.

-

A validator is added to the UNL, and it is not in the negative UNL.

-

A validator is removed from the UNL, and it is not in the negative UNL.

Case 3 and 4 are not affected by the negative UNL protocol.

Answer: No, because the negative UNL approach is safer.

First let’s compare the two approaches intuitively, (1) the negative UNL approach, and (2) lower quorum: simply lowering the quorum from 80% to 60% without the negative UNL. The negative UNL approach uses consensus to come up with a list of unreliable validators, which are then removed from the effective UNL temporarily. With this approach, the list of unreliable validators is agreed to by a quorum of validators and will be used by every node in the network to adjust its UNL. The quorum is always 80% of the effective UNL. The lower quorum approach is a tradeoff between safety and liveness and against our principle of preferring safety over liveness. Note that different validators don't have to agree on which validation sources they are ignoring.

Next we compare the two approaches quantitatively with examples, and apply Theorem 8 of Analysis of the XRP Ledger Consensus Protocol paper:

XRP LCP guarantees fork safety if Oi,j > nj / 2 + ni − qi + ti,j for every pair of nodes Pi, Pj,

where Oi,j is the overlapping requirement, nj and ni are UNL sizes, qi is the quorum size of Pi, ti,j = min(ti, tj, Oi,j), and ti and tj are the number of faults can be tolerated by Pi and Pj.

We denote UNLi as Pi's UNL, and |UNLi| as the size of Pi's UNL.

Assuming |UNLi| = |UNLj|, let's consider the following three cases:

-

With 80% quorum and 20% faults, Oi,j > 100% / 2 + 100% - 80% + 20% = 90%. I.e. fork safety requires > 90% UNL overlaps. This is one of the results in the analysis paper.

-

If the quorum is 60%, the relationship between the overlapping requirement and the faults that can be tolerated is Oi,j > 90% + ti,j. Under the same overlapping condition (i.e. 90%), to guarantee the fork safety, the network cannot tolerate any faults. So under the same overlapping condition, if the quorum is simply lowered, the network can tolerate fewer faults.

-

With the negative UNL approach, we want to argue that the inequation Oi,j > nj / 2 + ni − qi + ti,j is always true to guarantee fork safety, while the negative UNL protocol runs, i.e. the effective quorum is lowered without weakening the network's fault tolerance. To make the discussion easier, we rewrite the inequation as Oi,j > nj / 2 + (ni − qi) + min(ti, tj), where Oi,j is dropped from the definition of ti,j because Oi,j > min(ti, tj) always holds under the parameters we will use. Assuming a validator V is added to the negative UNL, now let's consider the 4 cases:

-

V is not on UNLi nor UNLj

The inequation holds because none of the variables change.

-

V is on UNLi but not on UNLj

The value of (ni − qi) is smaller. The value of min(ti, tj) could be smaller too. Other variables do not change. Overall, the left side of the inequation does not change, but the right side is smaller. So the inequation holds.

-

V is not on UNLi but on UNLj

The value of nj / 2 is smaller. The value of min(ti, tj) could be smaller too. Other variables do not change. Overall, the left side of the inequation does not change, but the right side is smaller. So the inequation holds.

-

V is on both UNLi and UNLj

The value of Oi,j is reduced by 1. The values of nj / 2, (ni − qi), and min(ti, tj) are reduced by 0.5, 0.2, and 1 respectively. The right side is reduced by 1.7. Overall, the left side of the inequation is reduced by 1, and the right side is reduced by 1.7. So the inequation holds.

The inequation holds for all the cases. So with the negative UNL approach, the network's fork safety is preserved, while the quorum is lowered that increases the network's liveness.

-

Question: We have observed that occasionally a validator wanders off on its own chain. How is this case handled by the negative UNL algorithm?

Answer: The case that a validator wanders off on its own chain can be measured with the validations agreement. Because the validations by this validator must be different from other validators' validations of the same sequence numbers. When there are enough disagreed validations, other validators will vote this validator onto the negative UNL.

In general by measuring the agreement of validations, we also measured the "sanity". If two validators have too many disagreements, one of them could be insane. When enough validators think a validator is insane, that validator is put on the negative UNL.

Question: Why would there be at most one disable UNLModify and one re-enable UNLModify transaction per flag ledger?

Answer: It is a design choice so that the effective UNL does not change too quickly. A typical targeted scenario is several validators go offline slowly during a long weekend. The current design can handle this kind of cases well without changing the effective UNL too quickly.

We will use two test networks, a single machine test network with multiple IP addresses and the QE test network with multiple machines. The single machine network will be used to test all the test cases and to debug. The QE network will be used after that. We want to see the test cases still pass with real network delay. A test case specifies:

- a UNL with different number of validators for different test cases,

- a network with zero or more non-validator nodes,

- a sequence of validator reliability change events (by killing/restarting nodes, or by running modified rippled that does not send all validation messages),

- the correct outcomes.

For all the test cases, the correct outcomes are verified by examining logs. We will grep the log to see if the correct negative UNLs are generated, and whether or not the network is making progress when it should be. The ripdtop tool will be helpful for monitoring validators' states and ledger progress. Some of the timing parameters of rippled will be changed to have faster ledger time. Most if not all test cases do not need client transactions.

For example, the test cases for the prototype:

- A 10-validator UNL.

- The network does not have other nodes.

- The validators will be started from the genesis. Once they start to produce ledgers, we kill five validators, one every flag ledger interval. Then we will restart them one by one.

- A sequence of events (or the lack of events) such as a killed validator is added to the negative UNL.

We considered testing with the current unit test framework, specifically the Consensus Simulation Framework (CSF). However, the CSF currently can only test the generic consensus algorithm as in the paper: Analysis of the XRP Ledger Consensus Protocol.