You are likely to be familiar with using a search and replace dialog (usually invoked with the Ctrl+H shortcut) to locate the occurrences of a particular string and replace it with something else. The sed command is a versatile and feature-rich version for search and replace operations, usable from the command line. An important feature that GUI applications may lack is regular expressions, a mini-programming language to precisely define a matching criteria.

This book heavily leans on examples to present features one by one. In addition to command options, regular expressions will also be discussed in detail. However, commands to manipulate data buffers and multiline techniques will be discussed only briefly and some commands are skipped entirely.

It is recommended that you manually type each example. Make an effort to understand the sample input as well as the solution presented and check if the output changes (or not!) when you alter some part of the input and the command. As an analogy, consider learning to drive a car — no matter how much you read about them or listen to explanations, you'd need practical experience to become proficient.

You should be familiar with command line usage in a Unix-like environment. You should also be comfortable with concepts like file redirection and command pipelines. Knowing the basics of the grep command will be handy in understanding the filtering features of sed.

If you are new to the world of the command line, check out my Computing from the Command Line ebook and curated resources on Linux CLI and Shell scripting before starting this book.

- The examples presented here have been tested with GNU sed version 4.9 and may include features not available in earlier versions.

- Code snippets are copy pasted from the

GNU bashshell and modified for presentation purposes. Some commands are preceded by comments to provide context and explanations. Blank lines to improve readability, onlyrealtime shown for speed comparisons, output skipped for commands likewgetand so on. - Unless otherwise noted, all examples and explanations are meant for ASCII input.

sedwould meanGNU sed,grepwould meanGNU grepand so on unless otherwise specified.- External links are provided throughout the book for you to explore certain topics in more depth.

- The learn_gnused repo has all the code snippets and files used in examples, exercises and other details related to the book. If you are not familiar with the

gitcommand, click the Code button on the webpage to get the files.

- GNU sed documentation — manual and examples

- stackoverflow and unix.stackexchange — for getting answers to pertinent questions on

sedand related commands - tex.stackexchange — for help on pandoc and

texrelated questions - /r/commandline/, /r/linux4noobs/, /r/linuxquestions/ and /r/linux/ — helpful forums

- canva — cover image

- oxipng, pngquant and svgcleaner — optimizing images

- Warning and Info icons by Amada44 under public domain

- arifmahmudrana for spotting an ambiguous explanation

Special thanks to all my friends and online acquaintances for their help, support and encouragement, especially during difficult times.

I would highly appreciate it if you'd let me know how you felt about this book. It could be anything from a simple thank you, pointing out a typo, mistakes in code snippets, which aspects of the book worked for you (or didn't!) and so on. Reader feedback is essential and especially so for self-published authors.

You can reach me via:

- Issue Manager: https://github.com/learnbyexample/learn_gnused/issues

- E-mail: [email protected]

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/learn_byexample

Sundeep Agarwal is a lazy being who prefers to work just enough to support his modest lifestyle. He accumulated vast wealth working as a Design Engineer at Analog Devices and retired from the corporate world at the ripe age of twenty-eight. Unfortunately, he squandered his savings within a few years and had to scramble trying to earn a living. Against all odds, selling programming ebooks saved his lazy self from having to look for a job again. He can now afford all the fantasy ebooks he wants to read and spends unhealthy amount of time browsing the internet.

When the creative muse strikes, he can be found working on yet another programming ebook (which invariably ends up having at least one example with regular expressions). Researching materials for his ebooks and everyday social media usage drowned his bookmarks, so he maintains curated resource lists for sanity sake. He is thankful for free learning resources and open source tools. His own contributions can be found at https://github.com/learnbyexample.

List of books: https://learnbyexample.github.io/books/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Code snippets are available under MIT License.

Resources mentioned in Acknowledgements section above are available under original licenses.

2.0

See Version_changes.md to track changes across book versions.

The command name sed is derived from stream editor. Here, stream refers to data being passed via shell pipes. Thus, the command's primary functionality is to act as a text editor for stdin data with stdout as the output target. It is now common to use sed on file inputs as well as in-place file editing.

This chapter will show how to install the latest sed version followed by details related to documentation. Then, you'll get an introduction to the substitute command, which is the most commonly used feature. The chapters to follow will add more details to the substitute command, discuss other commands and command line options. Cheatsheet, summary and exercises are also included at the end of these chapters.

If you are on a Unix-like system, you will most likely have some version of sed already installed. This book is primarily about GNU sed. As there are syntax and feature differences between various implementations, make sure to use GNU sed to follow along the examples presented in this book.

GNU sed is part of the text creation and manipulation tools and comes by default on GNU/Linux distributions. To install a particular version, visit gnu: sed software. See also release notes for an overview of changes between versions and bug list if you think some command isn't working as expected.

$ wget https://ftp.gnu.org/gnu/sed/sed-4.9.tar.xz

$ tar -Jxf sed-4.9.tar.xz

$ cd sed-4.9/

# see https://askubuntu.com/q/237576 if you get compiler not found error

$ ./configure

$ make

$ sudo make install

$ sed --version | head -n1

sed (GNU sed) 4.9If you are not using a Linux distribution, you may be able to access GNU sed using an option below:

- Git for Windows — provides a Bash emulation used to run Git from the command line

- Windows Subsystem for Linux — compatibility layer for running Linux binary executables natively on Windows

- brew — Package Manager for macOS (or Linux)

It is always good to know where to find documentation. From the command line, you can use man sed for a short manual and info sed for the full documentation. I prefer using the online gnu sed manual, which feels much easier to use and navigate.

$ man sed

SED(1) User Commands SED(1)

NAME

sed - stream editor for filtering and transforming text

SYNOPSIS

sed [-V] [--version] [--help] [-n] [--quiet] [--silent]

[-l N] [--line-length=N] [-u] [--unbuffered]

[-E] [-r] [--regexp-extended]

[-e script] [--expression=script]

[-f script-file] [--file=script-file]

[script-if-no-other-script]

[file...]

DESCRIPTION

Sed is a stream editor. A stream editor is used to perform basic

text transformations on an input stream (a file or input from a pipe‐

line). While in some ways similar to an editor which permits

scripted edits (such as ed), sed works by making only one pass over

the input(s), and is consequently more efficient. But it is sed's

ability to filter text in a pipeline which particularly distinguishes

it from other types of editors.For a quick overview of all the available options, use sed --help from the command line.

# only partial output shown here

$ sed --help

-n, --quiet, --silent

suppress automatic printing of pattern space

--debug

annotate program execution

-e script, --expression=script

add the script to the commands to be executed

-f script-file, --file=script-file

add the contents of script-file to the commands to be executed

--follow-symlinks

follow symlinks when processing in place

-i[SUFFIX], --in-place[=SUFFIX]

edit files in place (makes backup if SUFFIX supplied)

-l N, --line-length=N

specify the desired line-wrap length for the 'l' command

--posix

disable all GNU extensions.

-E, -r, --regexp-extended

use extended regular expressions in the script

(for portability use POSIX -E).

-s, --separate

consider files as separate rather than as a single,

continuous long stream.

--sandbox

operate in sandbox mode (disable e/r/w commands).

-u, --unbuffered

load minimal amounts of data from the input files and flush

the output buffers more often

-z, --null-data

separate lines by NUL characters

--help display this help and exit

--version output version information and exit

If no -e, --expression, -f, or --file option is given, then the first

non-option argument is taken as the sed script to interpret. All

remaining arguments are names of input files; if no input files are

specified, then the standard input is read.sed has various commands to manipulate text. The substitute command is the most commonly used operation, helps to replace matching text with something else. The syntax is s/REGEXP/REPLACEMENT/FLAGS where

sstands for the substitute command/is an idiomatic delimiter character to separate various portions of the commandREGEXPstands for regular expressionREPLACEMENTrefers to the replacement stringFLAGSare options to change the default behavior of the command

For now, it is enough to know that the s command is used for search and replace operations.

# input data that'll be passed to sed for editing

$ printf '1,2,3,4\na,b,c,d\n'

1,2,3,4

a,b,c,d

# for each input line, change only the first ',' to '-'

$ printf '1,2,3,4\na,b,c,d\n' | sed 's/,/-/'

1-2,3,4

a-b,c,d

# change all matches by adding the 'g' flag

$ printf '1,2,3,4\na,b,c,d\n' | sed 's/,/-/g'

1-2-3-4

a-b-c-dIn the above example, the input data is created using the printf command to showcase stream editing. By default, sed processes the input line by line. The newline character \n is the line separator by default. The first sed command replaces only the first occurrence of , with -. The second command replaces all occurrences as the g flag is also used (g stands for global).

As a good practice, always use single quotes around the script argument. Examples requiring shell interpretation will be discussed later.

If your input file has

\r\n(carriage return and newline characters) as the line ending, convert the input file to Unix-style before processing. See stackoverflow: Why does my tool output overwrite itself and how do I fix it? for a detailed discussion and mitigation methods.# Unix style $ printf '42\n' | file - /dev/stdin: ASCII text # DOS style $ printf '42\r\n' | file - /dev/stdin: ASCII text, with CRLF line terminators

Although sed derives its name from stream editing, it is common to use sed for file editing. To do so, you can pass one or more input filenames as arguments. You can use - to represent stdin as one of the input sources. By default, the modified data will go to the stdout stream and the input files are not modified. In-place file editing chapter will discuss how to apply the changes back to the source file(s).

The example_files directory has all the files used in the examples.

$ cat greeting.txt

Hi there

Have a nice day

# for each line, change the first occurrence of 'day' with 'weekend'

$ sed 's/day/weekend/' greeting.txt

Hi there

Have a nice weekend

# change all occurrences of 'e' to 'E'

# redirect modified data to another file

$ sed 's/e/E/g' greeting.txt > out.txt

$ cat out.txt

Hi thErE

HavE a nicE dayIn the previous section examples, every input line had matched the search expression. The first sed command here searched for day, which did not match the first line of greeting.txt file. By default, even if a line doesn't satisfy the search expression, it will be part of the output. You'll see how to get only the modified lines in the Print command section.

| Note | Description |

|---|---|

man sed |

brief manual |

sed --help |

brief description of all the command line options |

info sed |

comprehensive manual |

| online gnu sed manual | well formatted, easier to read and navigate |

s/REGEXP/REPLACEMENT/FLAGS |

syntax for the substitute command |

sed 's/,/-/' |

for each line, replace first , with - |

sed 's/,/-/g' |

replace all , with - |

This introductory chapter covered installation process, documentation and how to search and replace text using sed from the command line. In the coming chapters, you'll learn many more commands and features that make sed an important tool when it comes to command line text processing. One such feature is editing files in-place, which will be discussed in the next chapter.

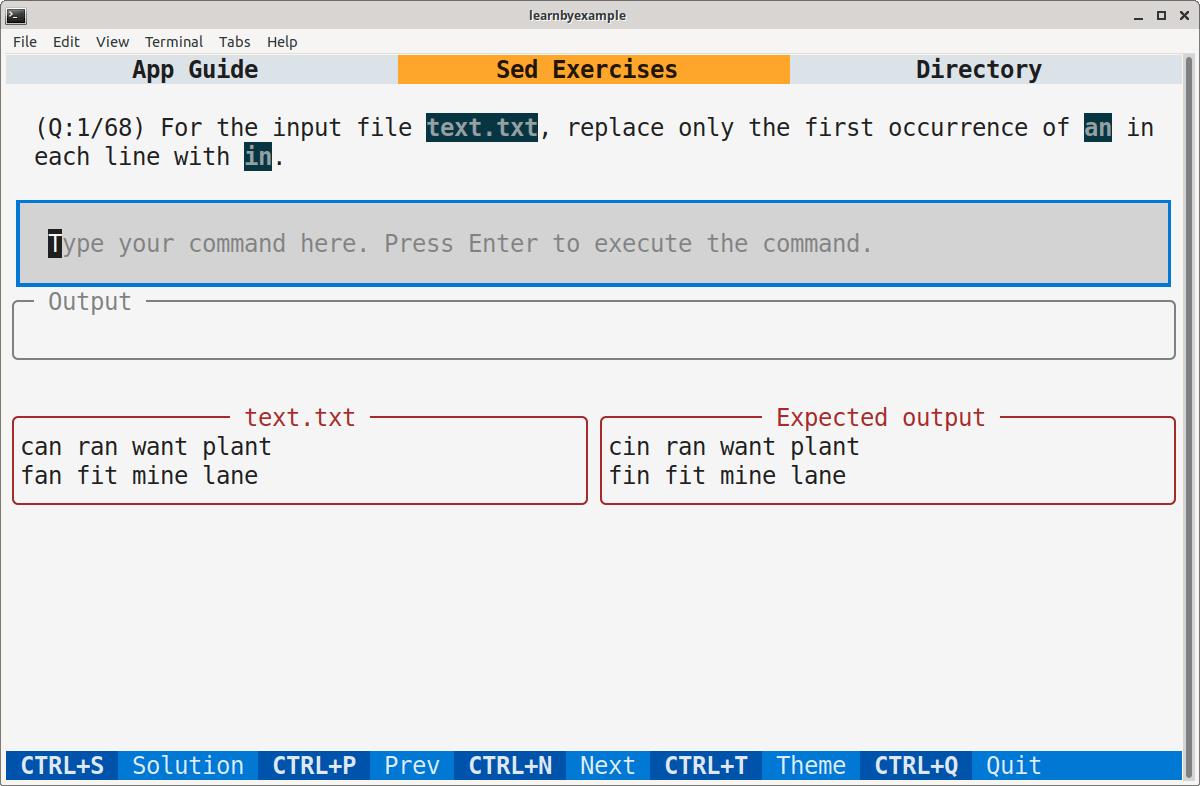

I wrote a TUI app to help you solve some of the exercises from this book interactively. See SedExercises repo for installation steps and app_guide.md for instructions on using this app.

Here's a sample screenshot:

All the exercises are also collated together in one place at Exercises.md. For solutions, see Exercise_solutions.md.

The exercises directory has all the files used in this section.

1) Replace only the first occurrence of 5 with five for the given stdin source.

$ echo 'They ate 5 apples and 5 mangoes' | sed ##### add your solution here

They ate five apples and 5 mangoes2) Replace all occurrences of 5 with five.

$ echo 'They ate 5 apples and 5 mangoes' | sed ##### add your solution here

They ate five apples and five mangoes3) Replace all occurrences of 0xA0 with 0x50 and 0xFF with 0x7F for the given input file.

$ cat hex.txt

start address: 0xA0, func1 address: 0xA0

end address: 0xFF, func2 address: 0xB0

$ sed ##### add your solution here

start address: 0x50, func1 address: 0x50

end address: 0x7F, func2 address: 0xB04) The substitute command searches and replaces sequences of characters. When you need to map one or more characters with another set of corresponding characters, you can use the y command. Quoting from the manual:

y/src/dst/ Transliterate any characters in the pattern space which match any of the source-chars with the corresponding character in dest-chars.

Use the y command to transform the given input string to get the output string as shown below.

$ echo 'goal new user sit eat dinner' | sed ##### add your solution here

gOAl nEw UsEr sIt EAt dInnEr5) Why does the following command produce an error? How'd you fix it?

$ echo 'a sunny day' | sed s/sunny day/cloudy day/

sed: -e expression #1, char 7: unterminated `s' command

# expected output

$ echo 'a sunny day' | sed ##### add your solution here

a cloudy dayIn the examples presented so far, the output from sed was displayed on the terminal or redirected to another file. This chapter will discuss how to write back the changes to the input files using the -i command line option. This option can be configured to make changes to the input files with or without creating a backup of original contents. When backups are needed, the original filename can get a prefix or a suffix or both. And the backups can be placed in the same directory or some other directory as needed.

The example_files directory has all the files used in the examples.

When an extension is provided as an argument to the -i option, the original contents of the input file gets preserved as per the extension given. For example, if the input file is ip.txt and -i.orig is used, the backup file will be named as ip.txt.orig.

$ cat colors.txt

deep blue

light orange

blue delight

# no output on terminal as -i option is used

# space is NOT allowed between -i and the extension

$ sed -i.bkp 's/blue/green/' colors.txt

# output from sed is written back to 'colors.txt'

$ cat colors.txt

deep green

light orange

green delight

# original file is preserved in 'colors.txt.bkp'

$ cat colors.txt.bkp

deep blue

light orange

blue delightSometimes backups are not desirable. In such cases, you can use the -i option without an argument. Be careful though, as changes made cannot be undone. It is recommended to test the command with sample inputs before applying the -i option on the actual file. You could also use the option with backup, compare the differences with a diff program and then delete the backup.

$ cat fruits.txt

banana

papaya

mango

$ sed -i 's/an/AN/g' fruits.txt

$ cat fruits.txt

bANANa

papaya

mANgoMultiple input files are treated individually and the changes are written back to respective files.

$ cat f1.txt

have a nice day

bad morning

what a pleasant evening

$ cat f2.txt

worse than ever

too bad

$ sed -i.bkp 's/bad/good/' f1.txt f2.txt

$ ls f?.*

f1.txt f1.txt.bkp f2.txt f2.txt.bkp

$ cat f1.txt

have a nice day

good morning

what a pleasant evening

$ cat f2.txt

worse than ever

too goodA * character in the argument to the -i option is special. It will get replaced with the input filename. This is helpful if you need to use a prefix instead of a suffix for the backup filename. Or any other combination that may be needed.

$ ls *colors*

colors.txt colors.txt.bkp

# single quotes is used here as * is a special shell character

$ sed -i'bkp.*' 's/green/yellow/' colors.txt

$ ls *colors*

bkp.colors.txt colors.txt colors.txt.bkpThe * trick can also be used to place the backups in another directory instead of the parent directory of input files. The backup directory should already exist for this to work.

$ mkdir backups

$ sed -i'backups/*' 's/good/nice/' f1.txt f2.txt

$ ls backups/

f1.txt f2.txt| Note | Description |

|---|---|

-i |

after processing, write back changes to the source file(s) |

| changes made cannot be undone, so use this option with caution | |

-i.bkp |

in addition to in-place editing, preserve original contents to a file |

whose name is derived from the input filename and .bkp as a suffix |

|

-i'bkp.*' |

* here gets replaced with the input filename |

| thus providing a way to add a prefix instead of a suffix | |

-i'backups/*' |

this will place the backup copy in a different existing directory |

| instead of source directory |

This chapter discussed about the -i option which is useful when you need to edit a file in-place. This is particularly useful in automation scripts. But, do ensure that you have tested the sed command before applying to actual files if you need to use this option without creating backups. In the next chapter, you'll learn filtering features of sed and how that helps to apply commands to only certain input lines instead of all the lines.

The exercises directory has all the files used in this section.

1) For the input file text.txt, replace all occurrences of in with an and write back the changes to text.txt itself. The original contents should get saved to text.txt.orig

$ cat text.txt

can ran want plant

tin fin fit mine line

$ sed ##### add your solution here

$ cat text.txt

can ran want plant

tan fan fit mane lane

$ cat text.txt.orig

can ran want plant

tin fin fit mine line2) For the input file text.txt, replace all occurrences of an with in and write back the changes to text.txt itself. Do not create backups for this exercise. Note that you should have solved the previous exercise before starting this one.

$ cat text.txt

can ran want plant

tan fan fit mane lane

$ sed ##### add your solution here

$ cat text.txt

cin rin wint plint

tin fin fit mine line

$ diff text.txt text.txt.orig

1c1

< cin rin wint plint

---

> can ran want plant3) For the input file copyright.txt, replace copyright: 2018 with copyright: 2019 and write back the changes to copyright.txt itself. The original contents should get saved to 2018_copyright.txt.bkp

$ cat copyright.txt

bla bla 2015 bla

blah 2018 blah

bla bla bla

copyright: 2018

$ sed ##### add your solution here

$ cat copyright.txt

bla bla 2015 bla

blah 2018 blah

bla bla bla

copyright: 2019

$ cat 2018_copyright.txt.bkp

bla bla 2015 bla

blah 2018 blah

bla bla bla

copyright: 20184) In the code sample shown below, two files are created by redirecting the output of the echo command. Then a sed command is used to edit b1.txt in-place as well as create a backup named bkp.b1.txt. Will the sed command work as expected? If not, why?

$ echo '2 apples' > b1.txt

$ echo '5 bananas' > -ibkp.txt

$ sed -ibkp.* 's/2/two/' b1.txt5) For the input file pets.txt, remove the first occurrence of I like from each line and write back the changes to pets.txt itself. The original contents should get saved with the same filename inside the bkp directory. Assume that you do not know whether bkp exists or not in the current working directory.

$ cat pets.txt

I like cats

I like parrots

I like dogs

##### add your solution here

$ cat pets.txt

cats

parrots

dogs

$ cat bkp/pets.txt

I like cats

I like parrots

I like dogsBy default, sed acts on the entire input content. Many a times, you want to act only upon specific portions of the input. To that end, sed has features to filter lines, similar to tools like grep, head and tail. sed can replicate most of grep's filtering features without too much fuss. And has additional features like line number based filtering, selecting lines between two patterns, relative addressing, etc. If you are familiar with functional programming, you would have come across the map, filter, reduce paradigm. A typical task with sed involves filtering a subset of input and then modifying (mapping) them. Sometimes, the subset is the entire input, as seen in the examples of previous chapters.

A tool optimized for a particular functionality should be preferred where possible.

grep,headandtailwould be better performance wise compared tosedfor equivalent line filtering solutions.

The example_files directory has all the files used in the examples.

As seen earlier, syntax for the substitute command is s/REGEXP/REPLACEMENT/FLAGS. The /REGEXP/FLAGS portion can be used as a conditional expression to allow commands to execute only for the lines matching the pattern.

# change commas to hyphens only if the input line contains '2'

# space between the filter and the command is optional

$ printf '1,2,3,4\na,b,c,d\n' | sed '/2/ s/,/-/g'

1-2-3-4

a,b,c,dUse /REGEXP/FLAGS! to act upon lines other than the matching ones.

# change commas to hyphens if the input line does NOT contain '2'

# space around ! is optional

$ printf '1,2,3,4\na,b,c,d\n' | sed '/2/! s/,/-/g'

1,2,3,4

a-b-c-d/REGEXP/ is one of the ways to define a filter, termed as address in the manual. Others will be covered later in this chapter.

Regular expressions will be discussed later. In this chapter, the examples with

/REGEXP/filtering will use only fixed strings (exact string comparison).

To delete the filtered lines, use the d command. Recall that all input lines are printed by default.

# same as: grep -v 'at'

$ printf 'sea\neat\ndrop\n' | sed '/at/d'

sea

dropTo get the default grep filtering, use the !d combination. Sometimes, negative logic can get confusing to use. It boils down to personal preference, similar to choosing between if and unless conditionals in programming languages.

# same as: grep 'at'

$ printf 'sea\neat\ndrop\n' | sed '/at/!d'

eat

Using an address is optional. So, for example,

sed '!d' filewould be equivalent to thecat filecommand.# same as: cat greeting.txt $ sed '!d' greeting.txt Hi there Have a nice day

To print the filtered lines, use the p command. But, recall that all input lines are printed by default. So, this command is typically used in combination with the -n option, which would turn off the default printing.

$ cat rhymes.txt

it is a warm and cozy day

listen to what I say

go play in the park

come back before the sky turns dark

There are so many delights to cherish

Apple, Banana and Cherry

Bread, Butter and Jelly

Try them all before you perish

# same as: grep 'warm' rhymes.txt

$ sed -n '/warm/p' rhymes.txt

it is a warm and cozy day

# same as: grep 'n t' rhymes.txt

$ sed -n '/n t/p' rhymes.txt

listen to what I say

go play in the parkThe substitute command provides p as a flag. In such a case, the modified line would be printed only if the substitution succeeded.

$ sed -n 's/warm/cool/gp' rhymes.txt

it is a cool and cozy day

# filter + substitution + p combination

$ sed -n '/the/ s/ark/ARK/gp' rhymes.txt

go play in the pARK

come back before the sky turns dARKUsing !p with the -n option will be equivalent to using the d command.

# same as: sed '/at/d'

$ printf 'sea\neat\ndrop\n' | sed -n '/at/!p'

sea

dropHere's an example of using the p command without the -n option.

# duplicate every line

$ seq 2 | sed 'p'

1

1

2

2The q command causes sed to exit immediately. Remaining commands and input lines will not be processed.

# quits after an input line containing 'say' is found

$ sed '/say/q' rhymes.txt

it is a warm and cozy day

listen to what I sayThe Q command is similar to q but won't print the matching line.

# matching line won't be printed

$ sed '/say/Q' rhymes.txt

it is a warm and cozy dayUse tac to get all lines starting from the last occurrence of the search string in the entire file.

$ tac rhymes.txt | sed '/an/q' | tac

Bread, Butter and Jelly

Try them all before you perishYou can optionally provide an exit status (from 0 to 255) along with the quit commands.

$ printf 'sea\neat\ndrop\n' | sed '/at/q2'

sea

eat

$ echo $?

2

$ printf 'sea\neat\ndrop\n' | sed '/at/Q3'

sea

$ echo $?

3

Be careful if you want to use

qorQcommands with multiple files, assedwill stop even if there are other files remaining to be processed. You could use a mixed address range as a workaround. See also unix.stackexchange: applying q to multiple files.

Commands seen so far can be specified more than once by separating them using ; or using the -e option multiple times. See sed manual: Multiple commands syntax for more details.

# print all input lines as well as the modified lines

$ printf 'sea\neat\ndrop\n' | sed -n -e 'p' -e 's/at/AT/p'

sea

eat

eAT

drop

# equivalent command to the above example using ; instead of -e

# space around ; is optional

$ printf 'sea\neat\ndrop\n' | sed -n 'p; s/at/AT/p'

sea

eat

eAT

dropYou can also separate the commands using a literal newline character. If many lines are needed, it is better to use a sed script instead.

# here, each command is separated by a literal newline character

# similar to $ representing the primary prompt PS1,

# > represents the secondary prompt PS2

$ sed -n '

> /the/ s/ark/ARK/gp

> s/warm/cool/gp

> s/Bread/Cake/gp

> ' rhymes.txt

it is a cool and cozy day

go play in the pARK

come back before the sky turns dARK

Cake, Butter and Jelly

Do not use multiple commands to construct conditional OR of multiple search strings, as you might get lines duplicated in the output as shown below. You can use regular expression feature alternation for such cases.

$ sed -ne '/play/p' -e '/ark/p' rhymes.txt go play in the park go play in the park come back before the sky turns dark

To execute multiple commands for a common filter, use {} to group the commands. You can also nest them if needed.

# spaces around {} is optional

$ printf 'gates\nnot\nused\n' | sed '/e/{s/s/*/g; s/t/*/g}'

ga*e*

not

u*ed

$ sed -n '/the/{s/for/FOR/gp; /play/{p; s/park/PARK/gp}}' rhymes.txt

go play in the park

go play in the PARK

come back beFORe the sky turns dark

Try them all beFORe you perishCommand grouping is an easy way to construct conditional AND of multiple search strings.

# same as: grep 'ark' rhymes.txt | grep 'play'

$ sed -n '/ark/{/play/p}' rhymes.txt

go play in the park

# same as: grep 'the' rhymes.txt | grep 'for' | grep 'urn'

$ sed -n '/the/{/for/{/urn/p}}' rhymes.txt

come back before the sky turns dark

# same as: grep 'for' rhymes.txt | grep -v 'sky'

$ sed -n '/for/{/sky/!p}' rhymes.txt

Try them all before you perishOther solutions using alternation feature of regular expressions and sed's control structures will be discussed later.

Line numbers can also be used as a filtering criteria.

# here, 3 represents the address for the print command

# same as: head -n3 rhymes.txt | tail -n1

# same as: sed '3!d'

$ sed -n '3p' rhymes.txt

go play in the park

# print 2nd and 6th line

$ sed -n '2p; 6p' rhymes.txt

listen to what I say

There are so many delights to cherish

# apply substitution only for the 2nd line

$ printf 'gates\nnot\nused\n' | sed '2 s/t/*/g'

gates

no*

usedAs a special case, $ indicates the last line of the input.

# same as: tail -n1 rhymes.txt

$ sed -n '$p' rhymes.txt

Try them all before you perishFor large input files, use the q command to avoid processing unnecessary input lines.

$ seq 3542 4623452 | sed -n '2452{p; q}'

5993

$ seq 3542 4623452 | sed -n '250p; 2452{p; q}'

3791

5993

# here is a sample time comparison

$ time seq 3542 4623452 | sed -n '2452{p; q}' > f1

real 0m0.005s

$ time seq 3542 4623452 | sed -n '2452p' > f2

real 0m0.121s

$ rm f1 f2Mimicking the head command using line number addressing and the q command.

# same as: seq 23 45 | head -n5

$ seq 23 45 | sed '5q'

23

24

25

26

27The = command will display the line numbers of matching lines.

# gives both the line number and matching lines

$ grep -n 'the' rhymes.txt

3:go play in the park

4:come back before the sky turns dark

9:Try them all before you perish

# gives only the line number of matching lines

# note the use of the -n option to avoid default printing

$ sed -n '/the/=' rhymes.txt

3

4

9If needed, matching line can also be printed. But there will be a newline character between the matching line and the line number.

$ sed -n '/what/{=; p}' rhymes.txt

2

listen to what I say

$ sed -n '/what/{p; =}' rhymes.txt

listen to what I say

2So far, filtering has been based on specific line number or lines matching the given REGEXP pattern. Address range gives the ability to define a starting address and an ending address separated by a comma.

# note that all the matching ranges are printed

$ sed -n '/to/,/pl/p' rhymes.txt

listen to what I say

go play in the park

There are so many delights to cherish

Apple, Banana and Cherry

# same as: sed -n '3,8!p'

$ seq 15 24 | sed '3,8d'

15

16

23

24Line numbers and REGEXP filtering can be mixed.

$ sed -n '6,/utter/p' rhymes.txt

There are so many delights to cherish

Apple, Banana and Cherry

Bread, Butter and Jelly

# same as: sed '/play/Q' rhymes.txt

# inefficient, but this will work for multiple file inputs

$ sed '/play/,$d' rhymes.txt

it is a warm and cozy day

listen to what I sayIf the second filtering condition doesn't match, lines starting from the first condition to the last line of the input will be matched.

# there's a line containing 'Banana' but the matching pair isn't found

$ sed -n '/Banana/,/XYZ/p' rhymes.txt

Apple, Banana and Cherry

Bread, Butter and Jelly

Try them all before you perishThe second address will always be used as a filtering condition only from the line that comes after the line that satisfied the first address. For example, if the same search pattern is used for both the addresses, there'll be at least two lines in output (assuming there are lines in the input after the first matching line).

$ sed -n '/w/,/w/p' rhymes.txt

it is a warm and cozy day

listen to what I say

# there's no line containing 'Cherry' after the 7th line

# so, rest of the file gets printed

$ sed -n '7,/Cherry/p' rhymes.txt

Apple, Banana and Cherry

Bread, Butter and Jelly

Try them all before you perishAs a special case, the first address can be 0 if the second one is a REGEXP filter. This allows the search pattern to be matched against the first line of the file.

# same as: sed '/cozy/q'

# inefficient, but this will work for multiple file inputs

$ sed -n '0,/cozy/p' rhymes.txt

it is a warm and cozy day

# same as: sed '/say/q'

$ sed -n '0,/say/p' rhymes.txt

it is a warm and cozy day

listen to what I sayThe grep command has an option -A that allows you to view lines that come after the matching lines. The sed command provides a similar feature when you prefix a + character to the number used in the second address. One difference compared to grep is that the context lines won't trigger a fresh matching of the first address.

# match a line containing 'the' and display the next line as well

# won't be same as: grep -A1 --no-group-separator 'the'

$ sed -n '/the/,+1p' rhymes.txt

go play in the park

come back before the sky turns dark

Try them all before you perish

# the first address can be a line number too

# helpful when it is programmatically constructed in a script

$ sed -n '6,+2p' rhymes.txt

There are so many delights to cherish

Apple, Banana and Cherry

Bread, Butter and JellyYou can construct an arithmetic progression with start and step values separated by the ~ symbol. i~j will filter lines numbered i+0j, i+1j, i+2j, i+3j, etc. So, 1~2 means all odd numbered lines and 5~3 means 5th, 8th, 11th, etc.

# print even numbered lines

$ seq 10 | sed -n '2~2p'

2

4

6

8

10

# delete lines numbered 2+0*4, 2+1*4, 2+2*4, etc (2, 6, 10, etc)

$ seq 7 | sed '2~4d'

1

3

4

5

7If i,~j is used (note the ,) then the meaning changes completely. After the start address, the closest line number which is a multiple of j will mark the end address. The start address can be REGEXP based filtering as well.

# here, closest multiple of 4 is the 4th line

$ seq 10 | sed -n '2,~4p'

2

3

4

# here, closest multiple of 4 is the 8th line

$ seq 10 | sed -n '5,~4p'

5

6

7

8

# line matching 'many' is the 6th line, closest multiple of 3 is the 9th line

$ sed -n '/many/,~3p' rhymes.txt

There are so many delights to cherish

Apple, Banana and Cherry

Bread, Butter and Jelly

Try them all before you perishSo far, the commands used have all been processing only one line at a time. The address range option provides the ability to act upon a group of lines, but the commands still operate one line at a time for that group. There are cases when you want a command to handle a string that contains multiple lines. As mentioned in the preface, this book will not cover advanced commands related to multiline processing and I highly recommend using awk or perl for such scenarios. However, this section will introduce two commands n and N which are relatively easier to use and will be seen in the coming chapters as well.

This is also a good place to get to know more details about how sed works. Quoting from sed manual: How sed Works:

sed maintains two data buffers: the active pattern space, and the auxiliary hold space. Both are initially empty.

sed operates by performing the following cycle on each line of input: first, sed reads one line from the input stream, removes any trailing newline, and places it in the pattern space. Then commands are executed; each command can have an address associated to it: addresses are a kind of condition code, and a command is only executed if the condition is verified before the command is to be executed.

When the end of the script is reached, unless the -n option is in use, the contents of pattern space are printed out to the output stream, adding back the trailing newline if it was removed. Then the next cycle starts for the next input line.

The pattern space buffer has only contained single line of input in all the examples seen so far. By using n and N commands, you can change the contents of the pattern space and use commands to act upon entire contents of this data buffer. For example, you can perform substitution on two or more lines at once.

First up, the n command. Quoting from sed manual: Often-Used Commands:

If auto-print is not disabled, print the pattern space, then, regardless, replace the pattern space with the next line of input. If there is no more input then sed exits without processing any more commands.

# same as: sed -n '2~2p'

# n will replace pattern space with the next line of input

# as -n option is used, the replaced line won't be printed

# the p command then prints the new line

$ seq 10 | sed -n 'n; p'

2

4

6

8

10

# if a line contains 't', replace pattern space with the next line

# substitute all 't' with 'TTT' for the new line thus fetched

# note that 't' wasn't substituted in the line that got replaced

# replaced pattern space gets printed as -n option is NOT used here

$ printf 'gates\nnot\nused\n' | sed '/t/{n; s/t/TTT/g}'

gates

noTTT

usedNext, the N command. Quoting from sed manual: Less Frequently-Used Commands:

Add a newline to the pattern space, then append the next line of input to the pattern space. If there is no more input then sed exits without processing any more commands.

When -z is used, a zero byte (the ascii 'NUL' character) is added between the lines (instead of a new line).

# append the next line to the pattern space

# and then replace newline character with colon character

$ seq 7 | sed 'N; s/\n/:/'

1:2

3:4

5:6

7

# if line contains 'at', the next line gets appended to the pattern space

# then the substitution is performed on the two lines in the buffer

$ printf 'gates\nnot\nused\n' | sed '/at/{N; s/s\nnot/d/}'

gated

used

See also sed manual: N command on the last line. Escape sequences like

\nwill be discussed in detail later.

See grymoire: sed tutorial if you wish to explore about the data buffers in detail and learn about the various multiline commands.

| Note | Description |

|---|---|

ADDR cmd |

Execute cmd only if the input line satisfies the ADDR condition |

ADDR can be REGEXP or line number or a combination of them |

|

/at/d |

delete all lines satisfying the given REGEXP |

/at/!d |

don't delete lines matching the given REGEXP |

/twice/p |

print all lines based on the given REGEXP |

as print is the default action, usually p is paired with -n option |

|

/not/ s/in/out/gp |

substitute only if line matches the given REGEXP |

| and print only if the substitution succeeds | |

/if/q |

quit immediately after printing the current pattern space |

| further input files, if any, won't be processed | |

/if/Q |

quit immediately without printing the current pattern space |

/at/q2 |

both q and Q can additionally use 0-255 as exit code |

-e 'cmd1' -e 'cmd2' |

execute multiple commands one after the other |

cmd1; cmd2 |

execute multiple commands one after the other |

| note that not all commands can be constructed this way | |

| commands can also be separated by a literal newline character | |

ADDR {cmds} |

group one or more commands to be executed for given ADDR |

| groups can be nested as well | |

ex: /in/{/not/{/you/p}} conditional AND of 3 REGEXPs |

|

2p |

line addressing, print only the 2nd line |

$ |

special address to indicate the last line of input |

2452{p; q} |

quit early to avoid processing unnecessary lines |

/not/= |

print line number instead of the matching line |

ADDR1,ADDR2 |

start and end addresses to operate upon |

| if ADDR2 doesn't match, lines till end of the file gets processed | |

/are/,/by/p |

print all groups of line matching the REGEXPs |

3,8d |

delete lines numbered 3 to 8 |

5,/use/p |

line number and REGEXP can be mixed |

0,/not/p |

inefficient equivalent of /not/q but works for multiple files |

ADDR,+N |

all lines matching the ADDR and N lines after |

i~j |

arithmetic progression with i as start and j as step |

ADDR,~j |

closest multiple of j w.r.t. the line matching the ADDR |

| pattern space | active data buffer, commands work on this content |

n |

if -n option isn't used, pattern space gets printed |

| and then pattern space is replaced with the next line of input | |

| exit without executing other commands if there's no more input | |

N |

add newline (or NUL for -z) to the pattern space |

| and then append the next line of input | |

| exit without executing other commands if there's no more input |

This chapter introduced the filtering capabilities of sed and how it can be combined with sed commands to process only lines of interest instead of the entire input contents. Filtering can be specified using a REGEXP, line number or a combination of them. You also learnt various ways to compose multiple sed commands. In the next chapter, you will learn syntax and features of regular expressions as supported by the sed command.

The exercises directory has all the files used in this section.

1) For the given input, display except the third line.

$ seq 34 37 | sed ##### add your solution here

34

35

372) Display only the fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh lines for the given input.

$ seq 65 78 | sed ##### add your solution here

68

69

70

713) For the input file addr.txt, replace all occurrences of are with are not and is with is not only from line number 4 till the end of file. Also, only the lines that were changed should be displayed in the output.

$ cat addr.txt

Hello World

How are you

This game is good

Today is sunny

12345

You are funny

$ sed ##### add your solution here

Today is not sunny

You are not funny4) Use sed to get the output shown below for the given input. You'll have to first understand the input to output transformation logic and then use commands introduced in this chapter to construct a solution.

$ seq 15 | sed ##### add your solution here

2

4

7

9

12

145) For the input file addr.txt, display all lines from the start of the file till the first occurrence of is.

$ sed ##### add your solution here

Hello World

How are you

This game is good6) For the input file addr.txt, display all lines that contain is but not good.

$ sed ##### add your solution here

Today is sunny7) n and N commands will not execute further commands if there are no more input lines to fetch. Correct the command shown below to get the expected output.

# wrong output

$ seq 11 | sed 'N; N; s/\n/-/g'

1-2-3

4-5-6

7-8-9

10

11

# expected output

$ seq 11 | sed ##### add your solution here

1-2-3

4-5-6

7-8-9

10-118) For the input file addr.txt, add line numbers in the format as shown below.

$ sed ##### add your solution here

1

Hello World

2

How are you

3

This game is good

4

Today is sunny

5

12345

6

You are funny9) For the input file addr.txt, print all lines that contain are and the line that comes after, if any.

$ sed ##### add your solution here

How are you

This game is good

You are funnyBonus: For the above input file, will sed -n '/is/,+1 p' addr.txt produce identical results as grep -A1 'is' addr.txt? If not, why?

10) Print all lines if their line numbers follow the sequence 1, 15, 29, 43, etc but not if the line contains 4 in it.

$ seq 32 100 | sed ##### add your solution here

32

60

8811) For the input file sample.txt, display from the start of the file till the first occurrence of are, excluding the matching line.

$ cat sample.txt

Hello World

Hi there

How are you

Just do-it

Believe it

banana

papaya

mango

Much ado about nothing

He he he

Adios amigo

$ sed ##### add your solution here

Hello World

Hi there12) For the input file sample.txt, display from the last occurrence of do till the end of the file.

##### add your solution here

Much ado about nothing

He he he

Adios amigo13) For the input file sample.txt, display from the 9th line till a line containing go.

$ sed ##### add your solution here

banana

papaya

mango14) For the input file sample.txt, display from a line containing it till the next line number that is divisible by 3.

$ sed ##### add your solution here

Just do-it

Believe it

banana15) Display only the odd numbered lines from addr.txt.

$ sed ##### add your solution here

Hello World

This game is good

12345This chapter covers Basic and Extended Regular Expressions as implemented in GNU sed. Unless otherwise indicated, examples and descriptions will assume ASCII input.

By default, sed treats the search pattern as Basic Regular Expression (BRE). The -E option enables Extended Regular Expression (ERE). Older sed versions used -r for ERE, which can still be used, but -E is more portable. In GNU sed, BRE and ERE only differ in how metacharacters are represented, there are no feature differences.

See also POSIX specification for BRE and ERE.

The example_files directory has all the files used in the examples.

Instead of matching anywhere in the line, restrictions can be specified. These restrictions are made possible by assigning special meaning to certain characters and escape sequences. The characters with special meaning are known as metacharacters in regular expressions parlance. In case you need to match those characters literally, you need to escape them with a \ character (discussed in the Matching the metacharacters section).

There are two line anchors:

^metacharacter restricts the match to the start of the line$metacharacter restricts the match to the end of the line

$ cat anchors.txt

sub par

spar

apparent effort

two spare computers

cart part tart mart

# lines starting with 's'

$ sed -n '/^s/p' anchors.txt

sub par

spar

# lines ending with 'rt'

$ sed -n '/rt$/p' anchors.txt

apparent effort

cart part tart mart

# change only whole line 'par'

$ printf 'spared no one\npar\nspar\n' | sed 's/^par$/PAR/'

spared no one

PAR

sparThe anchors can be used by themselves as a pattern too. Helps to insert text at the start/end of a input line, emulating string concatenation operations. This might not feel like a useful capability, but combined with other features they become quite a handy tool.

# add '* ' at the start of every input line

$ printf 'spared no one\npar\nspar\n' | sed 's/^/* /'

* spared no one

* par

* spar

# append '.' only if a line doesn't contain space characters

$ printf 'spared no one\npar\nspar\n' | sed '/ /! s/$/./'

spared no one

par.

spar.The second type of restriction is word anchors. A word character is any alphabet (irrespective of case), digit and the underscore character. You might wonder why there are digits and underscores as well, why not only alphabets? This comes from variable and function naming conventions — typically alphabets, digits and underscores are allowed. So, the definition is more programming oriented than natural language.

The escape sequence \b denotes a word boundary. This works for both the start of word and the end of word anchoring. Start of word means either the character prior to the word is a non-word character or there is no character (start of line). Similarly, end of word means the character after the word is a non-word character or no character (end of line). This implies that you cannot have word boundaries without a word character. Here are some examples:

$ cat anchors.txt

sub par

spar

apparent effort

two spare computers

cart part tart mart

# words starting with 'par'

$ sed -n '/\bpar/p' anchors.txt

sub par

cart part tart mart

# words ending with 'par'

$ sed -n '/par\b/p' anchors.txt

sub par

spar

# replace only whole word 'par'

$ sed -n 's/\bpar\b/***/p' anchors.txt

sub ***

Alternatively, you can use

\<to indicate the start of word anchor and\>to indicate the end of word anchor. Using\bis preferred as it is more commonly used in other regular expression implementations and has\Bas its opposite.

\bREGEXP\bbehaves a bit differently than\<REGEXP\>. See the Word boundary differences section for details.

The word boundary has an opposite anchor too. \B matches wherever \b doesn't match. This duality will be seen later with some other escape sequences too.

# match 'par' if it is surrounded by word characters

$ sed -n '/\Bpar\B/p' anchors.txt

apparent effort

two spare computers

# match 'par' but not at the start of a word

$ sed -n '/\Bpar/p' anchors.txt

spar

apparent effort

two spare computers

# match 'par' but not at the end of a word

$ sed -n '/par\B/p' anchors.txt

apparent effort

two spare computers

cart part tart mart

$ echo 'copper' | sed 's/\b/:/g'

:copper:

$ echo 'copper' | sed 's/\B/:/g'

c:o:p:p:e:r

Negative logic is handy in many text processing situations. But use it with care, you might end up matching things you didn't intend.

Many a times, you'd want to search for multiple terms. In a conditional expression, you can use the logical operators to combine multiple conditions. With regular expressions, the | metacharacter is similar to logical OR. The regular expression will match if any of the patterns separated by | is satisfied.

The | metacharacter syntax varies between BRE and ERE. Quoting from the manual:

In GNU sed, the only difference between basic and extended regular expressions is in the behavior of a few special characters:

?,+, parentheses, braces ({}), and|.

Here are some examples:

# BRE vs ERE

$ sed -n '/two\|sub/p' anchors.txt

sub par

two spare computers

$ sed -nE '/two|sub/p' anchors.txt

sub par

two spare computers

# match 'cat' or 'dog' or 'fox'

# note the use of 'g' flag for multiple replacements

$ echo 'cats dog bee parrot foxed' | sed -E 's/cat|dog|fox/--/g'

--s -- bee parrot --edHere's an example of alternate patterns with their own anchors:

# lines with whole word 'par' or lines ending with 's'

$ sed -nE '/\bpar\b|s$/p' anchors.txt

sub par

two spare computersThere are some tricky corner cases when using alternation. If it is used for filtering a line, there is no ambiguity. However, for use cases like substitution, it depends on a few factors. Say, you want to replace are or spared — which one should get precedence? The bigger word spared or the substring are inside it or based on something else?

The alternative which matches earliest in the input gets precedence.

# here, the output will be same irrespective of alternation order

# note that 'g' flag isn't used here, so only the first match gets replaced

$ echo 'cats dog bee parrot foxed' | sed -E 's/bee|parrot|at/--/'

c--s dog bee parrot foxed

$ echo 'cats dog bee parrot foxed' | sed -E 's/parrot|at|bee/--/'

c--s dog bee parrot foxedIn case of matches starting from the same location, for example spar and spared, the longest matching portion gets precedence. Unlike other regular expression implementations, left-to-right priority for alternation comes into play only if the length of the matches are the same. See Longest match wins and Backreferences sections for more examples. See regular-expressions: alternation for more information on this topic.

$ echo 'spared party parent' | sed -E 's/spa|spared/**/g'

** party parent

$ echo 'spared party parent' | sed -E 's/spared|spa/**/g'

** party parent

# other regexp flavors like Perl have left-to-right priority

$ echo 'spared party parent' | perl -pe 's/spa|spared/**/'

**red party parentOften, there are some common things among the regular expression alternatives. It could be common characters or qualifiers like the anchors. In such cases, you can group them using a pair of parentheses metacharacters. Similar to a(b+c)d = abd+acd in maths, you get a(b|c)d = abd|acd in regular expressions.

# without grouping

$ printf 'red\nreform\nread\ncrest\n' | sed -nE '/reform|rest/p'

reform

crest

# with grouping

$ printf 'red\nreform\nread\ncrest\n' | sed -nE '/re(form|st)/p'

reform

crest

# without grouping

$ sed -nE '/\bpar\b|\bpart\b/p' anchors.txt

sub par

cart part tart mart

# taking out common anchors

$ sed -nE '/\b(par|part)\b/p' anchors.txt

sub par

cart part tart mart

# taking out common characters as well

# you'll later learn a better technique instead of using empty alternate

$ sed -nE '/\bpar(|t)\b/p' anchors.txt

sub par

cart part tart martYou have already seen a few metacharacters and escape sequences that help compose a regular expression. To match the metacharacters literally, i.e. to remove their special meaning, prefix those characters with a \ character. To indicate a literal \ character, use \\. Some of the metacharacters, like the line anchors, lose their special meaning when not used in their customary positions with BRE syntax. If there are many metacharacters to be escaped, try to work out if the command can be simplified by switching between ERE and BRE.

# line anchors aren't special away from customary positions with BRE

$ printf 'a^2 + b^2 - C*3\nd = c^2' | sed -n '/b^2/p'

a^2 + b^2 - C*3

# but you'll have to escape them with ERE: sed -nE '/\$b/p'

$ printf '$a = $b + $c\n$x = 4' | sed -n '/$b/p'

$a = $b + $c

# here $ requires escaping even with BRE

$ echo '$a = $b + $c' | sed 's/\$//g'

a = b + c

# BRE vs ERE

$ printf '(a/b) + c\n3 + (a/b) - c\n' | sed -n '/^(a\/b)/p'

(a/b) + c

$ printf '(a/b) + c\n3 + (a/b) - c\n' | sed -nE '/^\(a\/b\)/p'

(a/b) + cHandling the replacement section metacharacters will be discussed in the Backreferences section.

The / character is idiomatically used as the REGEXP delimiter. But any character other than \ and the newline character can be used instead. This helps to avoid or reduce the need for escaping delimiter characters. The syntax is simple for substitution and transliteration commands, just use a different character instead of /.

# instead of this

$ echo '/home/learnbyexample/reports' | sed 's/\/home\/learnbyexample\//~\//'

~/reports

# use a different delimiter

$ echo '/home/learnbyexample/reports' | sed 's#/home/learnbyexample/#~/#'

~/reports

$ echo 'a/b/c/d' | sed 'y/a\/d/1-4/'

1-b-c-4

$ echo 'a/b/c/d' | sed 'y,a/d,1-4,'

1-b-c-4For address matching, syntax is a bit different — the first delimiter has to be escaped. For address ranges, start and end REGEXP can have different delimiters, as they are independent.

$ printf '/home/joe/1\n/home/john/1\n'

/home/joe/1

/home/john/1

# here ; is used as the delimiter

$ printf '/home/joe/1\n/home/john/1\n' | sed -n '\;/home/joe/;p'

/home/joe/1

See also a bit of history on why / is commonly used as the delimiter.

The dot metacharacter serves as a placeholder to match any character (including the newline character). Later you'll learn how to define your own custom placeholder for a limited set of characters.

# 3 character sequence starting with 'c' and ending with 't'

$ echo 'tac tin cot abc:tyz excited' | sed 's/c.t/-/g'

ta-in - ab-yz ex-ed

# any character followed by 3 and again any character

$ printf '42\t3500\n' | sed 's/.3.//'

4200

# N command is handy here to show that . matches \n as well

$ printf 'abc\nxyz\n' | sed 'N; s/c.x/ /'

ab yzAlternation helps you match one among multiple patterns. Combining the dot metacharacter with quantifiers (and alternation if needed) paves a way to perform logical AND between patterns. For example, to check if a string matches two patterns with any number of characters in between. Quantifiers can be applied to characters, groupings and some more constructs that'll be discussed later. Apart from the ability to specify exact quantity and bounded range, these can also match unbounded varying quantities.

First up, the ? metacharacter which quantifies a character or group to match 0 or 1 times. This helps to define optional patterns and build terser patterns.

# same as: sed -E 's/\b(fe.d|fed)\b/X/g'

# BRE version: sed 's/fe.\?d\b/X/g'

$ echo 'fed fold fe:d feeder' | sed -E 's/\bfe.?d\b/X/g'

X fold X feeder

# same as: sed -nE '/\bpar(|t)\b/p'

$ sed -nE '/\bpart?\b/p' anchors.txt

sub par

cart part tart mart

# same as: sed -E 's/part|parrot/X/g'

$ echo 'par part parrot parent' | sed -E 's/par(ro)?t/X/g'

par X X parent

# same as: sed -E 's/part|parrot|parent/X/g'

$ echo 'par part parrot parent' | sed -E 's/par(en|ro)?t/X/g'

par X X X

# matches '<' or '\<' and they are both replaced with '\<'

$ echo 'apple \< fig ice < apple cream <' | sed -E 's/\\?</\\</g'

apple \< fig ice \< apple cream \<The * metacharacter quantifies a character or group to match 0 or more times.

# 'f' followed by zero or more of 'e' followed by 'd'

$ echo 'fd fed fod fe:d feeeeder' | sed 's/fe*d/X/g'

X X fod fe:d Xer

# zero or more of '1' followed by '2'

$ echo '3111111111125111142' | sed 's/1*2/-/g'

3-511114-The + metacharacter quantifies a character or group to match 1 or more times.

# 'f' followed by one or more of 'e' followed by 'd'

# BRE version: sed 's/fe\+d/X/g'

$ echo 'fd fed fod fe:d feeeeder' | sed -E 's/fe+d/X/g'

fd X fod fe:d Xer

# one or more of '1' followed by optional '4' and then '2'

$ echo '3111111111125111142' | sed -E 's/1+4?2/-/g'

3-5-You can specify a range of integer numbers, both bounded and unbounded, using {} metacharacters. There are four ways to use this quantifier as listed below:

| Quantifier | Description |

|---|---|

{m,n} |

match m to n times |

{m,} |

match at least m times |

{,n} |

match up to n times (including 0 times) |

{n} |

match exactly n times |

# note that stray characters like space are not allowed anywhere within {}

# BRE version: sed 's/ab\{1,4\}c/X/g'

$ echo 'ac abc abbc abbbc abbbbbbbbc' | sed -E 's/ab{1,4}c/X/g'

ac X X X abbbbbbbbc

$ echo 'ac abc abbc abbbc abbbbbbbbc' | sed -E 's/ab{3,}c/X/g'

ac abc abbc X X

$ echo 'ac abc abbc abbbc abbbbbbbbc' | sed -E 's/ab{,2}c/X/g'

X X X abbbc abbbbbbbbc

$ echo 'ac abc abbc abbbc abbbbbbbbc' | sed -E 's/ab{3}c/X/g'

ac abc abbc X abbbbbbbbc

With ERE, you have escape

{to represent it literally. Unlike), you don't have to escape the}character.$ echo 'a{5} = 10' | sed -E 's/a\{5}/x/' x = 10 $ echo 'report_{a,b}.txt' | sed -E 's/_{a,b}/_c/' sed: -e expression #1, char 12: Invalid content of \{\} $ echo 'report_{a,b}.txt' | sed -E 's/_\{a,b}/_c/' report_c.txt

Next up, constructing AND conditional using dot metacharacter and quantifiers.

# match 'Error' followed by zero or more characters followed by 'valid'

$ echo 'Error: not a valid input' | sed -n '/Error.*valid/p'

Error: not a valid inputTo allow matching in any order, you'll have to bring in alternation as well.

# 'cat' followed by 'dog' or 'dog' followed by 'cat'

$ echo 'two cats and a dog' | sed -E 's/cat.*dog|dog.*cat/pets/'

two pets

$ echo 'two dogs and a cat' | sed -E 's/cat.*dog|dog.*cat/pets/'

two petsYou've already seen an example where the longest matching portion was chosen if the alternatives started from the same location. For example spar|spared will result in spared being chosen over spar. The same applies whenever there are two or more matching possibilities from same starting location. For example, f.?o will match foo instead of fo if the input string to match is foot.

# longest match among 'foo' and 'fo' wins here

$ echo 'foot' | sed -E 's/f.?o/X/'

Xt

# everything will match here

$ echo 'car bat cod map scat dot abacus' | sed 's/.*/X/'

X

# longest match happens when (1|2|3)+ matches up to '1233' only

# so that '12apple' can match as well

$ echo 'fig123312apple' | sed -E 's/g(1|2|3)+(12apple)?/X/'

fiX

# in other implementations like Perl, that is not the case

# precedence is left-to-right for greedy quantifiers

$ echo 'fig123312apple' | perl -pe 's/g(1|2|3)+(12apple)?/X/'

fiXappleWhile determining the longest match, the overall regular expression matching is also considered. That's how Error.*valid example worked. If .* had consumed everything after Error, there wouldn't be any more characters to try to match valid. So, among the varying quantity of characters to match for .*, the longest portion that satisfies the overall regular expression is chosen. Something like a.*b will match from the first a in the input string to the last b. In other implementations, like Perl, this is achieved through a process called backtracking. These approaches have their own advantages and disadvantages and have cases where the pattern can result in exponential time consumption.

# from the start of line to the last 'b' in the line

$ echo 'car bat cod map scat dot abacus' | sed 's/.*b/-/'

-acus

# from the first 'b' to the last 't' in the line

$ echo 'car bat cod map scat dot abacus' | sed 's/b.*t/-/'

car - abacus

# from the first 'b' to the last 'at' in the line

$ echo 'car bat cod map scat dot abacus' | sed 's/b.*at/-/'

car - dot abacus

# here 'm*' will match 'm' zero times as that gives the longest match

$ echo 'car bat cod map scat dot abacus' | sed 's/a.*m*/-/'

c-To create a custom placeholder for limited set of characters, enclose them inside [] metacharacters. It is similar to using single character alternations inside a grouping, but with added flexibility and features. Character classes have their own versions of metacharacters and provide special predefined sets for common use cases. Quantifiers are also applicable to character classes.

# same as: sed -nE '/cot|cut/p' and sed -nE '/c(o|u)t/p'

$ printf 'cute\ncat\ncot\ncoat\ncost\nscuttle\n' | sed -n '/c[ou]t/p'

cute

cot

scuttle

# same as: sed -nE '/.(a|e|o)t/p'

$ printf 'meeting\ncute\nboat\nat\nfoot\n' | sed -n '/.[aeo]t/p'

meeting

boat

foot

# same as: sed -E 's/\b(s|o|t)(o|n)\b/X/g'

$ echo 'no so in to do on' | sed 's/\b[sot][on]\b/X/g'

no X in X do X

# lines made up of letters 'o' and 'n', line length at least 2

# words.txt contains dictionary words, one word per line

$ sed -nE '/^[on]{2,}$/p' words.txt

no

non

noon

onCharacter classes have their own metacharacters to help define the sets succinctly. Metacharacters outside of character classes like ^, $, () etc either don't have special meaning or have a completely different one inside the character classes.

First up, the - metacharacter that helps to define a range of characters instead of having to specify them all individually.

# same as: sed -E 's/[0123456789]+/-/g'

$ echo 'Sample123string42with777numbers' | sed -E 's/[0-9]+/-/g'

Sample-string-with-numbers

# whole words made up of lowercase alphabets and digits only

$ echo 'coat Bin food tar12 best' | sed -E 's/\b[a-z0-9]+\b/X/g'

X Bin X X X

# whole words made up of lowercase alphabets, starting with 'p' to 'z'

$ echo 'road i post grip read eat pit' | sed -E 's/\b[p-z][a-z]*\b/X/g'

X i X grip X eat XCharacter classes can also be used to construct numeric ranges. However, it is easy to miss corner cases and some ranges are complicated to construct.

# numbers between 10 to 29

$ echo '23 154 12 26 34' | sed -E 's/\b[12][0-9]\b/X/g'

X 154 X X 34

# numbers >= 100 with optional leading zeros

$ echo '0501 035 154 12 26 98234' | sed -E 's/\b0*[1-9][0-9]{2,}\b/X/g'

X 035 X 12 26 XNext metacharacter is ^ which has to specified as the first character of the character class. It negates the set of characters, so all characters other than those specified will be matched. As highlighted earlier, handle negative logic with care, you might end up matching more than you wanted.

# replace all non-digit characters

$ echo 'Sample123string42with777numbers' | sed -E 's/[^0-9]+/-/g'

-123-42-777-

# delete last two columns

$ echo 'apple:123:banana:cherry' | sed -E 's/(:[^:]+){2}$//'

apple:123

# sequence of characters surrounded by double quotes

$ echo 'I like "mango" and "guava"' | sed -E 's/"[^"]+"/X/g'

I like X and X

# sometimes it is simpler to positively define a set than negation

# same as: sed -n '/^[^aeiou]*$/p'

$ printf 'tryst\nfun\nglyph\npity\nwhy\n' | sed '/[aeiou]/d'

tryst

glyph

whySome commonly used character sets have predefined escape sequences:

\wmatches all word characters[a-zA-Z0-9_](recall the description for word boundaries)\Wmatches all non-word characters (recall duality seen earlier, like\band\B)\smatches all whitespace characters: tab, newline, vertical tab, form feed, carriage return and space\Smatches all non-whitespace characters

These escape sequences cannot be used inside character classes. Also, as mentioned earlier, these definitions assume ASCII input.

# match all non-word characters

$ echo 'load;err_msg--\nant,r2..not' | sed -E 's/\W+/-/g'

load-err_msg-nant-r2-not

# replace all sequences of whitespaces with a single space

$ printf 'hi \v\f there.\thave \ra nice\t\tday\n' | sed -E 's/\s+/ /g'

hi there. have a nice day

# \w would simply match \ and w inside character classes

$ echo 'w=y\x+9*3' | sed 's/[\w=]//g'

yx+9*3

seddoesn't support\dand\D, commonly featured in other implementations as a shortcut for all the digits and non-digits.# \d will match just the 'd' character $ echo '42\d123' | sed -E 's/\d+/-/g' 42\-123 # \d here matches all digit characters $ echo '42\d123' | perl -pe 's/\d+/-/g' -\d-

A named character set is defined by a name enclosed between [: and :] and has to be used within a character class [], along with other characters as needed.

| Named set | Description |

|---|---|

[:digit:] |

[0-9] |

[:lower:] |

[a-z] |

[:upper:] |

[A-Z] |

[:alpha:] |

[a-zA-Z] |

[:alnum:] |

[0-9a-zA-Z] |

[:xdigit:] |

[0-9a-fA-F] |

[:cntrl:] |

control characters — first 32 ASCII characters and 127th (DEL) |

[:punct:] |

all the punctuation characters |

[:graph:] |

[:alnum:] and [:punct:] |

[:print:] |

[:alnum:], [:punct:] and space |

[:blank:] |

space and tab characters |

[:space:] |

whitespace characters, same as \s |

Here are some examples:

$ s='err_msg xerox ant m_2 P2 load1 eel'

$ echo "$s" | sed -E 's/\b[[:lower:]]+\b/X/g'

err_msg X X m_2 P2 load1 X

$ echo "$s" | sed -E 's/\b[[:lower:]_]+\b/X/g'

X X X m_2 P2 load1 X

$ echo "$s" | sed -E 's/\b[[:alnum:]]+\b/X/g'

err_msg X X m_2 X X X

$ echo ',pie tie#ink-eat_42' | sed -E 's/[^[:punct:]]+//g'

,#-_Specific placement is needed to match character class metacharacters literally.

- should be the first or the last character.

# same as: sed -E 's/[-a-z]{2,}/X/g'

$ echo 'ab-cd gh-c 12-423' | sed -E 's/[a-z-]{2,}/X/g'

X X 12-423] should be the first character.

# no match

$ printf 'int a[5]\nfig\n1+1=2\n' | sed -n '/[=]]/p'

# correct usage

$ printf 'int a[5]\nfig\n1+1=2\n' | sed -n '/[]=]/p'

int a[5]

1+1=2[ can be used anywhere in the character set, but not combinations like [. or [:. Using [][] will match both [ and ].

$ echo 'int a[5]' | sed -n '/[x[.y]/p'

sed: -e expression #1, char 9: unterminated address regex

$ echo 'int a[5]' | sed -n '/[x[y.]/p'

int a[5]^ should be other than the first character.

$ echo 'f*(a^b) - 3*(a+b)/(a-b)' | sed 's/a[+^]b/c/g'

f*(c) - 3*(c)/(a-b)

As seen in the examples above, combinations like

[.or[:cannot be used together to mean two individual characters, as they have special meaning within[]. See Character Classes and Bracket Expressions section ininfo sedfor more details.

Certain ASCII characters like tab \t, carriage return \r, newline \n, etc have escape sequences to represent them. Additionally, any character can be represented using their ASCII value in decimal \dNNN or octal \oNNN or hexadecimal \xNN formats. Unlike character set escape sequences like \w, these can be used inside character classes. As \ is special inside character class, use \\ to represent it literally (technically, this is only needed if the combination of \ and the character(s) that follows is a valid escape sequence).

# \t represents the tab character

$ printf 'apple\tbanana\tcherry\n' | sed 's/\t/ /g'

apple banana cherry

$ echo 'a b c' | sed 's/ /\t/g'

a b c

# these escape sequence work inside character class too

$ printf 'a\t\r\fb\vc\n' | sed -E 's/[\t\v\f\r]+/:/g'

a:b:c

# representing single quotes

# use \d039 and \o047 for decimal and octal respectively

$ echo "universe: '42'" | sed 's/\x27/"/g'

universe: "42"

$ echo 'universe: "42"' | sed 's/"/\x27/g'

universe: '42'If a metacharacter is specified using the ASCII value format in the search section, it will still act as the metacharacter. However, metacharacters specified using the ASCII value format in the replacement section acts as a literal character. Undefined escape sequences (both search and replacement section) will be treated as the character it escapes, for example, \e will match e (not \ and e).

# \x5e is ^ character, acts as line anchor here

$ printf 'cute\ncot\ncat\ncoat\n' | sed -n '/\x5eco/p'

cot

coat

# & metacharacter in replacement will be discussed in the next section

# it represents the entire matched portion

$ echo 'hello world' | sed 's/.*/"&"/'

"hello world"

# \x26 is & character, acts as a literal character here

$ echo 'hello world' | sed 's/.*/"\x26"/'

"&"

See sed manual: Escapes for full list and details such as precedence rules. See also stackoverflow: behavior of ASCII value format inside character classes.

The grouping metacharacters () are also known as capture groups. Similar to variables in programming languages, the portion captured by () can be referred later using backreferences. The syntax is \N where N is the capture group you want. Leftmost ( in the regular expression is \1, next one is \2 and so on up to \9. Backreferences can be used in both the search and replacement sections.

# whole words that have at least one consecutive repeated character

# word boundaries are not needed here as longest match wins

$ echo 'effort flee facade oddball rat tool' | sed -E 's/\w*(\w)\1\w*/X/g'

X X facade X rat X

# reduce \\ to \ and delete if it is a single \

$ echo '\[\] and \\w and \[a-zA-Z0-9\_\]' | sed -E 's/(\\?)\\/\1/g'

[] and \w and [a-zA-Z0-9_]

# remove two or more duplicate words separated by spaces

# \b prevents false matches like 'the theatre', 'sand and stone' etc

$ echo 'aa a a a 42 f_1 f_1 f_13.14' | sed -E 's/\b(\w+)( \1)+\b/\1/g'

aa a 42 f_1 f_13.14

# 8 character lines having the same 3 lowercase letters at the start and end

$ sed -nE '/^([a-z]{3})..\1$/p' words.txt

mesdames

respires

restores

testates\0 or & represents the entire matched string in the replacement section.

# duplicate the first column value and add it as the final column

# same as: sed -E 's/^([^,]+).*/\0,\1/'

$ echo 'one,2,3.14,42' | sed -E 's/^([^,]+).*/&,\1/'

one,2,3.14,42,one

# surround the entire line with double quotes

$ echo 'hello world' | sed 's/.*/"&"/'

"hello world"

$ echo 'hello world' | sed 's/.*/Hi. &. Have a nice day/'

Hi. hello world. Have a nice dayIf a quantifier is applied on a pattern grouped inside () metacharacters, you'll need an outer () group to capture the matching portion. Other regular expression engines like PCRE (Perl Compatible Regular Expressions) provide non-capturing groups to handle such cases. In sed you'll have to consider the extra capture groups.

# uppercase the first letter of the first column (\u will be discussed later)

# surround the third column with double quotes

# note the numbers used in the replacement section

$ echo 'one,2,3.14,42' | sed -E 's/^(([^,]+,){2})([^,]+)/\u\1"\3"/'

One,2,"3.14",42Here's an example where alternation order matters when the matching portions have the same length. Aim is to delete all whole words unless it starts with g or p and contains y. See stackoverflow: Non greedy matching in sed for another use case.

$ s='tryst,fun,glyph,pity,why,group'

# all words get deleted because \b\w+\b gets priority here

$ echo "$s" | sed -E 's/\b\w+\b|(\b[gp]\w*y\w*\b)/\1/g'

,,,,,

# capture group gets priority here, so words in the capture group are retained

$ echo "$s" | sed -E 's/(\b[gp]\w*y\w*\b)|\b\w+\b/\1/g'

,,glyph,pity,,As \ and & are special characters in the replacement section, use \\ and \& respectively for literal representation.

$ echo 'apple and fig' | sed 's/and/[&]/'

apple [and] fig

$ echo 'apple and fig' | sed 's/and/[\&]/'

apple [&] fig

$ echo 'apple and fig' | sed 's/and/\\/'

apple \ fig

Backreference will provide the string that was matched, not the pattern that was inside the capture group. For example, if

([0-9][a-f])matches3b, then backreferencing will give3band not any other valid match like8f,0aetc. This is akin to how variables behave in programming, only the expression result stays after variable assignment, not the expression itself.

Visit sed bug list for known issues.

Here's an issue for certain usage of backreferences and quantifier that was filed by yours truly.

# takes some time and results in no output

# aim is to get words having two occurrences of repeated characters

# works if you use perl -ne 'print if /^(\w*(\w)\2\w*){2}$/'

$ sed -nE '/^(\w*(\w)\2\w*){2}$/p' words.txt | head -n5

# works when nesting is unrolled

$ sed -nE '/^\w*(\w)\1\w*(\w)\2\w*$/p' words.txt | head -n5

Abbott

Annabelle

Annette

Appaloosa

Appleseedunix.stackexchange: Why doesn't this sed command replace the 3rd-to-last "and"? shows another interesting bug when word boundaries and group repetition are involved. Some examples are shown below. Again, workaround is to expand the group.

# wrong output

$ echo 'cocoa' | sed -nE '/(\bco){2}/p'

cocoa

# correct behavior, no output

$ echo 'cocoa' | sed -nE '/\bco\bco/p'

# wrong output, there's only 1 whole word 'it' after 'with'

$ echo 'it line with it here sit too' | sed -E 's/with(.*\bit\b){2}/XYZ/'

it line XYZ too

# correct behavior, input isn't modified

$ echo 'it line with it here sit too' | sed -E 's/with.*\bit\b.*\bit\b/XYZ/'

it line with it here sit tooChanging word boundaries to \< and \> results in a different issue:

# this correctly doesn't modify the input

$ echo 'it line with it here sit too' | sed -E 's/with(.*\<it\>){2}/XYZ/'

it line with it here sit too

# this correctly modifies the input