On Organizational Skills and the Applied Science of Gluing Lots of Things Together in the Xraft of Software ngineering

Some weeks ago, a bright individual reposted on Hacker News a well-thought out and succinct post about the most important skill in software development. In this essay, John D. Cook reflect on the article Organizational Skills Beat Algorithmic Wizardry, by James Hague. Both authors tackle the software engineering subject of organization as a skill. They contrast organizational skill to the mastery of computer science tested in interviews, taught in academia, or touted in blog posts. Their contemplation got me pondering about how interview skill are organized.

Thinking deeply about both authors’ messages, I ran through my interview experiences over time and I empathize with those who experience technical interviews that are not classically trained.

My last experience was disorganized, explaining my experience in a legacy system.

My last completed professional project was a multi-year old system that dealt with code complexity, and a never-ending rolling line of products. We fought bravely to organize the growing mess. Both thoughts had a common thread, as they were small and large exercises in organization. They revolved around feelings of anxiety, vulnerability, stress, and happy moments. I (we) cared deeply about outcomes.

This motivated me to write a follow-up. Why not answer questions posed? So I kicked the idea back and forth and hung on one question. John asked:

...how do you present a clever bit of organization?

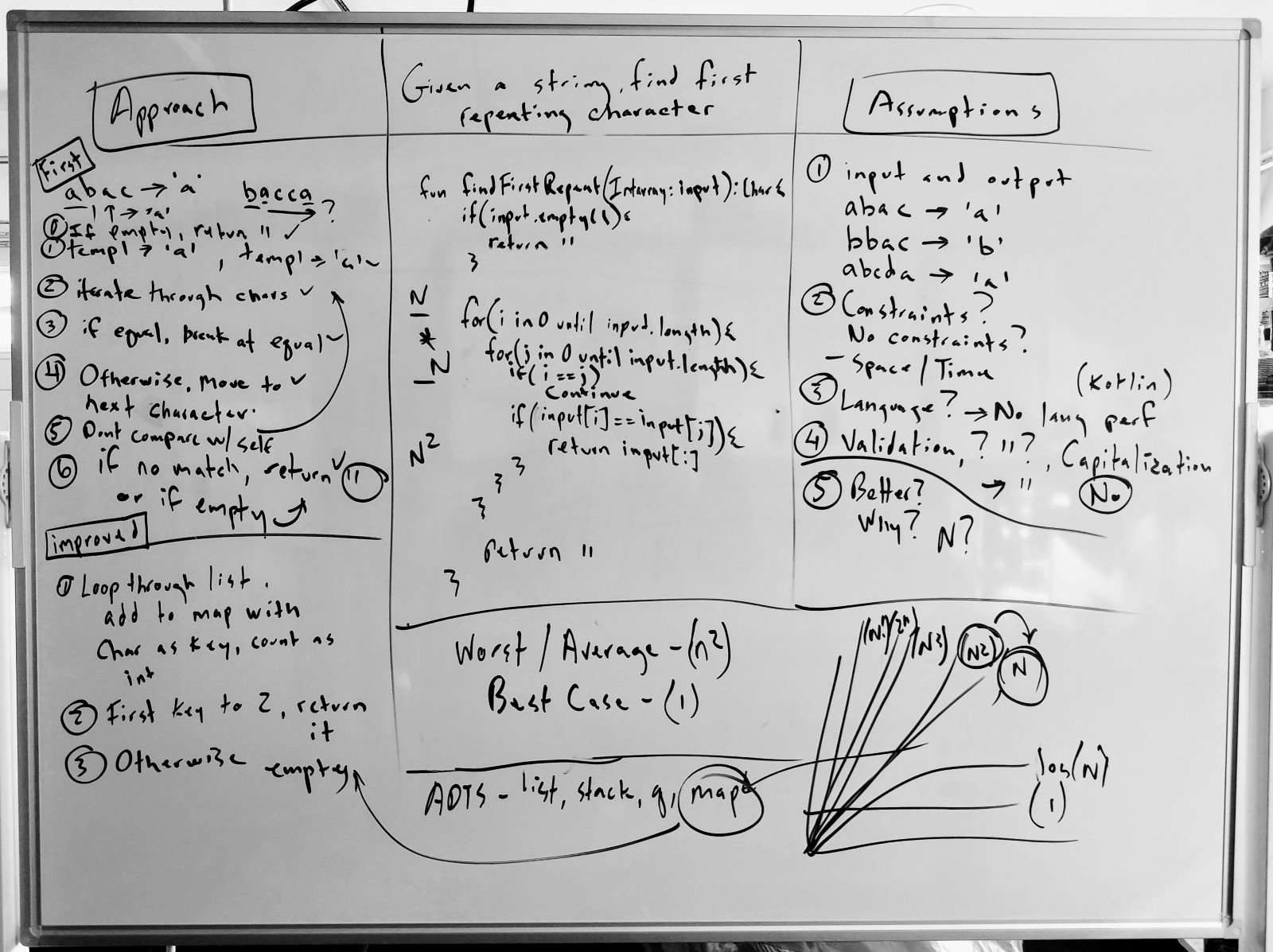

Thinking about the question, I looked away from the screen and saw my whiteboard standing before me. My head swirled around the posts. Tough technical interviews? Organization? Managing state? Collapsing weight? Code complexity? Perhaps the technical interview whiteboard exercise could prove a salient point of software engineering all along.

So I solved some problems at the whiteboard, confidently, all by myself.

Rarely at a whiteboard does anyone perform well. You have to hold a lot in your head, and demonstrate a didactic process. You have to communicate, but how do you communicate while ignoring the voice in your head that says “hurry up!” while moving around enthusiastically?

At technical companies, there are whiteboard technical interviews. A candidate is placed in a room with a whiteboard with an individual who represents the company. They ask a question and we are invited to solve the problem. Then it’s usually up to the interviewee to drive the problem to a solution.

This is where my head starts to spin out of control with anxiety and disorganization. Trumpets begin to play in my mind and my thought process becomes mangled. Time speeds up. My vision narrows and I become lightheaded.

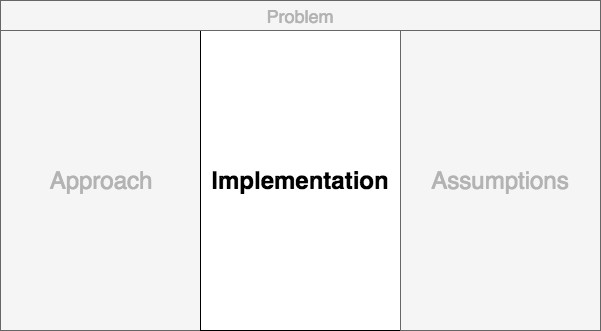

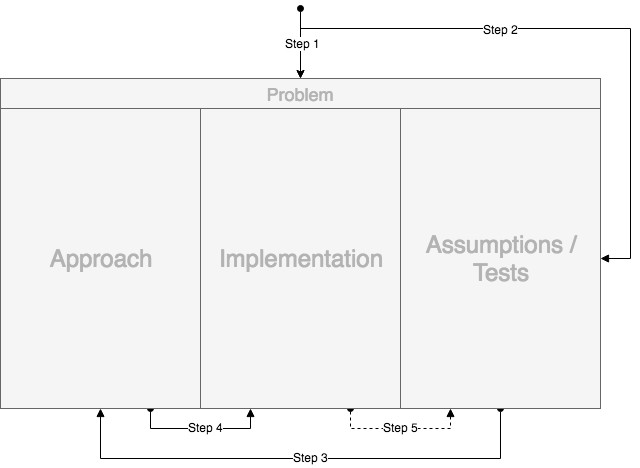

Maybe there is a way to slow down, pace, and walk through a process with organization. Something I’ve never seen before while interviewing candidates over my years, but maybe a process can help ease the nerves and make it an enjoyable experience. To start, look at the board, and cut it up into three sections. They will be organized.

Make sure to write down the problem in a complete sentence up top. This will get you feeling the marker and will help you overcome the initial hit of the rush of "how do I solve this?"

Once you have the question written down, look at it for a moment and start to think about questions. Draw the lines with ample space. Don’t worry about the pause, let the interviewer know that you are thinking about questions to ask.

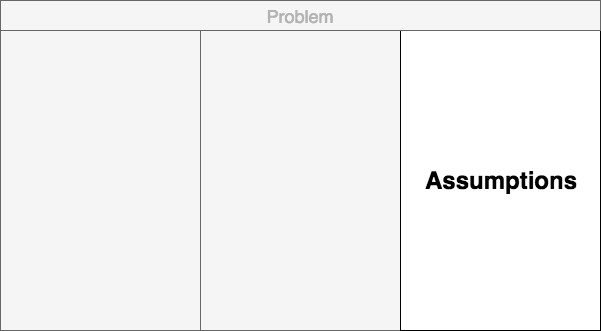

Think about some generic questions. Like, what programming language do you prefer? Move to the right side of the board. No questions coming? The problem may contain concepts you don’t know. Ask what they are. Then, start tackling the problem questions. The first question to ask is an example of the input and output. Ask if the data is presorted. Write the functional and non-functional requirements.

Clarifying assumptions can simplify the problem. As you ask each question, write each answer pair in the assumptions area. When you receive answers, get a second marker to highlight the answer. Bringing your own markers may help.

We can only hold so many items in our head, so lean on the board to capture all the knowledge. Writing the questions and answers out will slow down your approach so it is digestible.

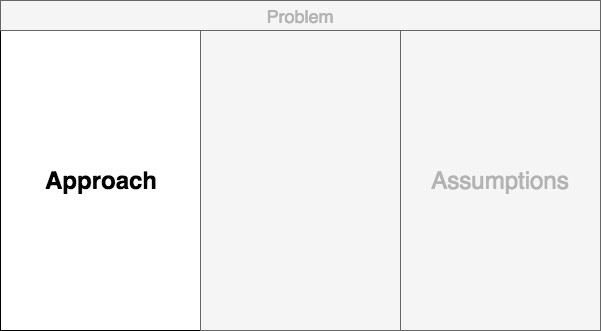

Once you have a good number of questions on the right side of the board, physically move over to the left. This is where we will start to discuss an approach to solve our problem..

Here, very rough pseudocode, steps, and visualizations occur. Let your interviewer know that this is not your implementation, but a place where you are organizing your thoughts on the strategy approach, with data structures and abstract data types. Draw out the solution like it's a picture.

The left box will reveal holes in our questions. As you write out your approach, stop the process if a question remains unanswered. Walk back to the right section, and write out the question and try to receive the answer.

At the absolute minimum, this will happen a few times as you recognize the average cases, best cases, and worst cases. It depends on the strategy, the limits and the constraints. Request relaxation on approaches such as “For this example, can I use a small set of data?” “Can I assume the input array is sorted?” Input validation is also another question generator.

Once enough approach material is generated, you are now ready to write through your implementation with confidence. You will be supported by both sides. Highlight and point to each step as you write the code. Carefully step through the approach, listed to your left. As you write your implementation, go back and forth double-checking the assumptions.

Even if you struggle with the solution, you are a wizard of organization.

Of course, there is a possibility of finding improvements in the act. Walk back to the left and revive the approach, break it down or ask for assistance. New questions pop up. Go to the right. Go back and forth from left to right to center until you succeed. You will.

Be the master of organization. If you hit a wall or find something that is just not right, remember that the sides will guide you.

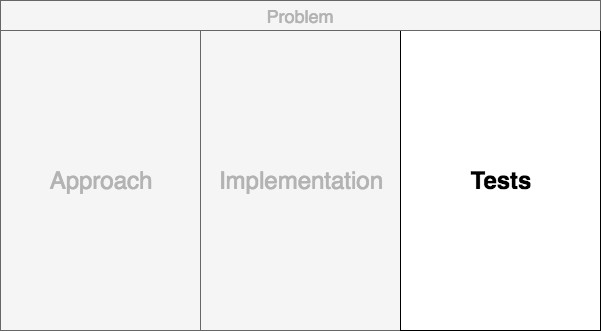

If you have completed the exercise to the satisfaction of the interviewer, take the step to discuss how the solution should be tested. Use the assumptions section as a place to write test code, if you should choose to do so.

By now, it is likely safe to remove all the questions from this area. Erase the questions and write unit tests. In the end, you’ll be okay because you organized with confidence.

There you go. That was a few minutes of pure organization without theory. The process leans on a few simple concepts.

Sectioning — slicing up the problem in pieces from start to finish. Scaffolding — the concept of temporary architecture, a supporting structure as we build around us. Gating — we should proceed forward with the next step when we are confident about addressing the problem. Actively engage the interviewer with “Did I miss any assumptions?” or “Does my approach have holes?” before proceeding. State — organization is handled visually to maintain the weighing the complexity of the problem. Avoid using an eraser.

Let's finish by examining important quotes by John Cook.

You can’t appreciate a feat of organization until you experience the disorganization.

I agree. This applies to projects with code, people, and those technical whiteboard experiences. But to take a step back and answer the problem with a process of organization is a feat of engineering. I’ve learned that:

The key to engineering is potential organization. A large kinetic energy comes from the act of organizing astutely and continuously over time.

John D. Cook said:

Only if the disorganized mess is your responsibility, something that means more to you than a case study, can you wrap your head around it and appreciate improvements.

We all have a story about the whiteboard – and we all have the stories of defeat. So, I found a way to improve my engineering mind at the same time. The result is what you have read.

Computer program is applied science, a pattern language and a craft. I’ve written a few posts about organization linking organization to system complexity. This is why I appreciated John Cook's and James Hague's thoughts on software organization.

Walk through the steps, and you’ll do great. Good luck in your next interview!

If you find yourself in this situation, ask for a larger whiteboard!

This author does not claim to be an expert at the practice.

Since this chapter was written, many resources have appeared to assist interviewees with system design interview prep.

This author recommends ByteByteGo’s System Design Interview Volume 1 and Volume 2 by Alex Xu and Sahn Lam. More information can be found at bytebytego.com.