XGBoost is short for "Extreme Gradient Boosting", where the term "Gradient Boosting" is proposed in the paper Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine, by Friedman. XGBoost is based on this original model. This is a tutorial on gradient boosted trees, and most of the content is based on these slides by the author of xgboost.

The GBM (boosted trees) has been around for really a while, and there are a lot of materials on the topic. This tutorial tries to explain boosted trees in a self-contained and principled way using the elements of supervised learning. We think this explanation is cleaner, more formal, and motivates the variant used in xgboost.

XGBoost is used for supervised learning problems, where we use the training data $ x_i $ to predict a target variable $ y_i $.

Before we dive into trees, let us start by reviewing the basic elements in supervised learning.

The model in supervised learning usually refers to the mathematical structure of how to make the prediction $ y_i $ given $ x_i $.

For example, a common model is a linear model, where the prediction is given by $ \hat{y}_i = \sum_j w_j x_{ij} $, a linear combination of weighted input features.

The prediction value can have different interpretations, depending on the task.

For example, it can be logistic transformed to get the probability of positive class in logistic regression, and it can also be used as a ranking score when we want to rank the outputs.

The parameters are the undetermined part that we need to learn from data. In linear regression problems, the parameters are the coefficients $ w $.

Usually we will use $ \Theta $ to denote the parameters.

Based on different understandings of $ y_i $ we can have different problems, such as regression, classification, ordering, etc.

We need to find a way to find the best parameters given the training data. In order to do so, we need to define a so-called objective function,

to measure the performance of the model given a certain set of parameters.

A very important fact about objective functions is they must always contain two parts: training loss and regularization.

where $ L $ is the training loss function, and $ \Omega $ is the regularization term. The training loss measures how predictive our model is on training data.

For example, a commonly used training loss is mean squared error.

Another commonly used loss function is logistic loss for logistic regression

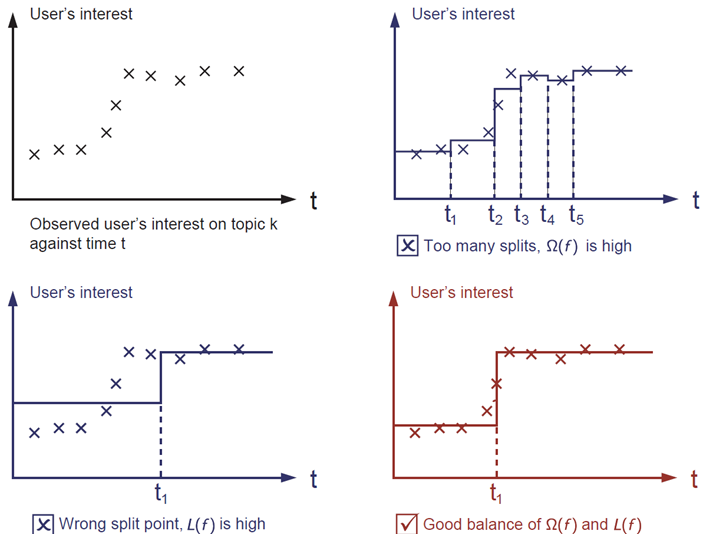

The regularization term is what people usually forget to add. The regularization term controls the complexity of the model, which helps us to avoid overfitting. This sounds a bit abstract, so let us consider the following problem in the following picture. You are asked to fit visually a step function given the input data points on the upper left corner of the image. Which solution among the three do you think is the best fit?

The answer is already marked as red. Please think if it is reasonable to you visually. The general principle is we want a simple and predictive model. The tradeoff between the two is also referred as bias-variance tradeoff in machine learning.

The elements introduced above form the basic elements of supervised learning, and they are naturally the building blocks of machine learning toolkits. For example, you should be able to describe the differences and commonalities between boosted trees and random forests. Understanding the process in a formalized way also helps us to understand the objective that we are learning and the reason behind the heuristics such as pruning and smoothing.

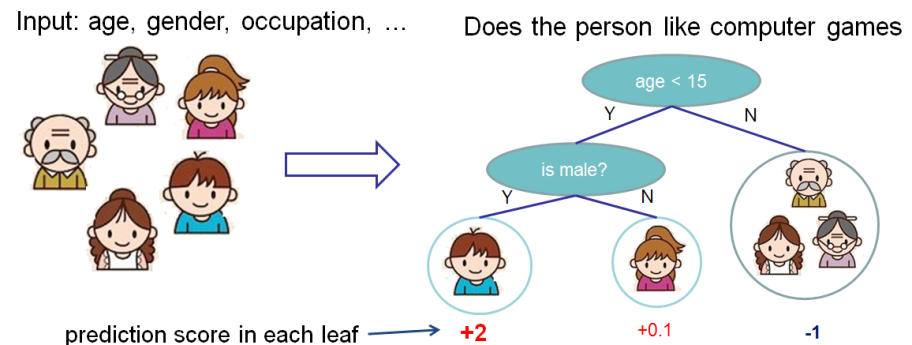

Now that we have introduced the elements of supervised learning, let us get started with real trees. To begin with, let us first learn about the model of xgboost: tree ensembles. The tree ensemble model is a set of classification and regression trees (CART). Here's a simple example of a CART that classifies whether someone will like computer games.

We classify the members of a family into different leaves, and assign them the score on corresponding leaf. A CART is a bit different from decision trees, where the leaf only contains decision values. In CART, a real score is associated with each of the leaves, which gives us richer interpretations that go beyond classification. This also makes the unified optimization step easier, as we will see in later part of this tutorial.

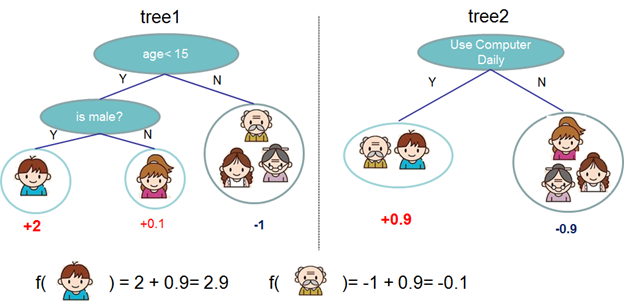

Usually, a single tree is not strong enough to be used in practice. What is actually used is the so-called tree ensemble model, that sums the prediction of multiple trees together.

Here is an example of tree ensemble of two trees. The prediction scores of each individual tree are summed up to get the final score. If you look at the example, an important fact is that the two trees try to complement each other. Mathematically, we can write our model in the form

where $ K $ is the number of trees, $ f $ is a function in the functional space $ \mathcal{F} $, and $ \mathcal{F} $ is the set of all possible CARTs. Therefore our objective to optimize can be written as

Now here comes the question, what is the model for random forests? It is exactly tree ensembles! So random forests and boosted trees are not different in terms of model, the difference is how we train them. This means if you write a predictive service of tree ensembles, you only need to write one of them and they should directly work for both random forests and boosted trees. One example of why elements of supervised learning rocks.

After introducing the model, let us begin with the real training part. How should we learn the trees? The answer is, as is always for all supervised learning models: define an objective function, and optimize it!

Assume we have the following objective function (remember it always need to contain training loss, and regularization)

$$Obj = \sum_{i=1}^n l(y_i, \hat{y}_i^{(t)}) + \sum_{i=1}^t\Omega(f_i) \\$$First thing we want to ask is what are the parameters of trees.

You can find what we need to learn are those functions $f_i$, with each containing the structure

of the tree and the leaf scores. This is much harder than traditional optimization problem where you can take the gradient and go.

It is not easy to train all the trees at once.

Instead, we use an additive strategy: fix what we have learned, add one new tree at a time.

We note the prediction value at step $t$ by $ \hat{y}_i^{(t)}$, so we have

It remains to ask, which tree do we want at each step? A natural thing is to add the one that optimizes our objective.

If we consider using MSE as our loss function, it becomes the following form.

The form of MSE is friendly, with a first order term (usually called residual) and a quadratic term. For other losses of interest (for example, logistic loss), it is not so easy to get such a nice form. So in the general case, we take the Taylor expansion of the loss function up to the second order

where the $g_i$ and $h_i$ are defined as

After we remove all the constants, the specific objective at step $t$ becomes

This becomes our optimization goal for the new tree. One important advantage of this definition is that

it only depends on $g_i$ and $h_i$. This is how xgboost can support custom loss functions.

We can optimize every loss function, including logistic regression, weighted logistic regression, using exactly

the same solver that takes $g_i$ and $h_i$ as input!

We have introduced the training step, but wait, there is one important thing, the regularization!

We need to define the complexity of the tree $\Omega(f)$. In order to do so, let us first refine the definition of the tree a tree $ f(x) $ as

Here $ w $ is the vector of scores on leaves, $ q $ is a function assigning each data point to the corresponding leaf and$ T $ is the number of leaves.

In XGBoost, we define the complexity as

Of course there is more than one way to define the complexity, but this specific one works well in practice. The regularization is one part most tree packages treat less carefully, or simply ignore. This was because the traditional treatment of tree learning only emphasized improving impurity, while the complexity control was left to heuristics. By defining it formally, we can get a better idea of what we are learning, and yes it works well in practice.

Here is the magical part of the derivation. After reformalizing the tree model, we can write the objective value with the $ t$-th tree as:

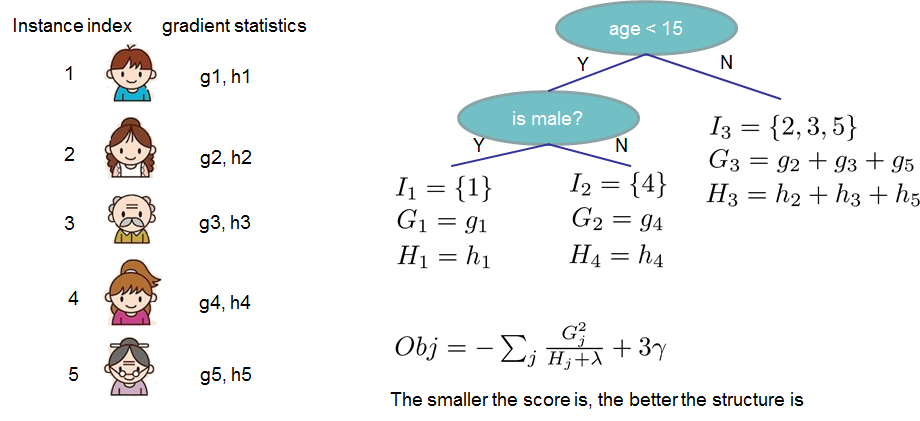

where $ I_j = \{i|q(x_i)=j\} $ is the set of indices of data points assigned to the $ j $-th leaf.

Notice that in the second line we have changed the index of the summation because all the data points on the same leaf get the same score.

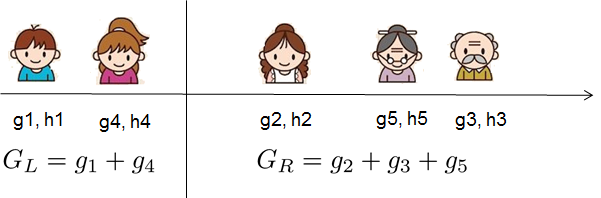

We could further compress the expression by defining $ G_j = \sum_{i\in I_j} g_i $ and $ H_j = \sum_{i\in I_j} h_i $:

In this equation $ w_j $ are independent to each other, the form $ G_jw_j+\frac{1}{2}(H_j+\lambda)w_j^2 $ is quadratic and the best $ w_j $ for a given structure $q(x)$ and the best objective reduction we can get is:

The last equation measures how good a tree structure $q(x)$ is.

If all this sounds a bit complicated, let's take a look at the picture, and see how the scores can be calculated.

Basically, for a given tree structure, we push the statistics $g_i$ and $h_i$ to the leaves they belong to,

sum the statistics together, and use the formula to calculate how good the tree is.

This score is like the impurity measure in a decision tree, except that it also takes the model complexity into account.

Now that we have a way to measure how good a tree is, ideally we would enumerate all possible trees and pick the best one. In practice it is intractable, so we will try to optimize one level of the tree at a time. Specifically we try to split a leaf into two leaves, and the score it gains is

This formula can be decomposed as 1) the score on the new left leaf 2) the score on the new right leaf 3) The score on the original leaf 4) regularization on the additional leaf.

We can see an important fact here: if the gain is smaller than $\gamma$, we would do better not to add that branch. This is exactly the pruning techniques in tree based

models! By using the principles of supervised learning, we can naturally come up with the reason these techniques work :)

For real valued data, we usually want to search for an optimal split. To efficiently do so, we place all the instances in sorted order, like the following picture.

Then a left to right scan is sufficient to calculate the structure score of all possible split solutions, and we can find the best split efficiently.

Now that you understand what boosted trees are, you may ask, where is the introduction on XGBoost? XGBoost is exactly a tool motivated by the formal principle introduced in this tutorial! More importantly, it is developed with both deep consideration in terms of systems optimization and principles in machine learning. The goal of this library is to push the extreme of the computation limits of machines to provide a scalable, portable and accurate library. Make sure you try it out, and most importantly, contribute your piece of wisdom (code, examples, tutorials) to the community!