The United States is currently experiencing a large outbreak of hepatitis A. Since the introduction of the vaccine in 1996 the number of hepatitis A cases was steadily declining - until 2016 when the first cases of the current outbreak were traced. Vaccination is the primary method to control hepatitis A and the near real-time estimate of the incidence is crucial for predicting the dynamics of the outbreak and planning an effective vaccination strategy. However, the routine surveillance data for the ongoing hepatitis A outbreak from the Center for Disease Control (CDC) is usually delayed. In our study we introduced an innovative approach of using the combination of provisional data from CDC and non-traditional data sources. As a result, we were able to effectively model the outbreak and predict the percentage of population which needs to be vaccinated in California and Kentucky to stop the outbreak.

Infection with hepatitis A virus is one of the most common causes of acute hepatitis worldwide. It’s a highly contagious disease that can lead to serious morbidity and occasional mortality. Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is transmitted via fecal-oral route usually via contaminated food or water or through close physical contact with the infected person [1]. The incidence of the disease in the United States has steadily declined since the introduction of the vaccine in 1996. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends routine vaccination of all children at the age of one year old and adults from high-risk groups – people traveling to endemic areas, men who have sex with men, patients with chronic liver disease, injection-drug users. While routine childhood hepatitis A vaccination has provided higher immunity protection in younger populations, many susceptible adults remain unvaccinated [2].

Between 2001 and 2015 the annual incidence of HAV infection continued its decrease falling by 86.9 % - from 10,615 cases in 2001 to 1,390 in 2015. In 2016, the first cases of the current outbreak were reported which led to an increased number of HAV infection cases – 2,007 [3]. From January 2017 to April 2018, CDC received more than 2,500 reports of hepatitis A infections associated with person-to-person transmission from multiple states. Of those reports for which risk factors are known, 68% of the infected persons report drug use (injection and non-injection), homelessness, or both [4]. The high incidence of HAV infection was also reported among men who have sex with men (MSM) in New York state during the first six months in 2017 [5]. The numbers of hospitalizations and deaths during the current outbreak have been higher than what is normally reported through national surveillance of hepatitis A. While in 2016 the number of hospitalizations due to HAV infection was 41.6% and number of deaths was 0.7%, during the outbreak these numbers reached 71% and 3%, respectively [3,6]. The severity of the infection may be attributable to preexisting chronic illnesses, including hepatitis B and C infections, other comorbidities, age and risk behaviors common among drug users and homeless [6,7].

The outbreak which started in 2016 hit the new highs in the end of 2018 - beginning 2019. In May 2019, the local Departments of Health from 21 states reported more than 17,000 outbreak-related cases. It shows an almost 600% increase in the number of cases since April 2018 and Kentucky is an infamous leader where 4,621 cases of infection and 57 deaths were confirmed [8, 9]. It is obvious that the rapid spread of HAV infection among under-privileged population can bring us back into the pre-vaccine era.

During the time of the research, the routine surveillance data for the ongoing hepatitis A outbreak from CDC was not available and it limited opportunities to plan an effective vaccination response across the affected states. Lack of surveillance data prompted us to the combination of provisional reports from CDC WONDER and news articles from HealthMap. The usage of non-traditional data sources is an emerging trend in global healthcare and it has already shown utility in augmenting traditional approaches in tracking infectious diseases outbreaks when the surveillance data is missing [10-12].

Our main research question was to (1) model the outbreak to predict the % of the susceptible population which should be vaccinated to stop the current hepatitis A outbreak.

However, the lack of the availability of near to real-time data triggered us to extend our research and (2) evaluate whether news media data can be a sufficient proxy to traditional surveillance data in order to model the disease propagation in real time.

Finally, we wanted to (3) explore the additional insights that the news media could reveal.

We started our research by analyzing the available structured data for all of the 20 states affected by the outbreak. The initial observations demonstrated that California and Kentucky will be the most representative states for the purpose of our research because they represent the populations at-risk the best. California was the first state to declare hepatitis A outbreak in 2017 with 724 cases of infections and 21 deaths as of February 2019. The virus spread was mostly among homeless populations of San Diego, Santa Cruz and Los Angeles. California has also appeared to be one of the most referential examples because it holds the 24% of total homeless population in the US. The recent increase in homeless population nearly doubled in the past ten years and it can explain the rapid spread of the disease [13]. Effective vaccination campaigns, hygiene promotion and shelter sanitation helped to contain the outbreak in less than a year and stop it in November 2018 [14].

In Kentucky we have observed the opposite situation - the outbreak is currently ongoing with more than 4,500 cases and the state outbreak accounts for more than ⅓ of all the deaths in the country. The disease is mostly spread among people who use drugs. The entire state is considered vulnerable for HIV and HCV epidemics among injection drug users with 54 counties (45 %) receiving CDC funding for syringe service programs [15]. Kentucky is also among the top five states with the highest number of drug overdose-related deaths [16].

Therefore, in our study we decided to focus on the outbreak dynamics in two states - California and Kentucky, as these states represent two different populations at risk for hepatitis A.

For the purpose of the research we used the following structured and unstructured data sets.

- The CDC WONDER cases dataset.

CDC WONDER (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research) is a search engine to select datasets from CDC. We extracted the weekly reports on Hepatitis A incidence that are voluntarily submitted by local health departments to National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System and our dataset comprised of the reports from 4/3/2017 till 3/31/2019. [17].

- HealthMap news cases.

HealthMap is a publicly available database that contains disease-related news articles. There were 568 news articles in HealthMap that talk about Hepatitis A outbreak from 3/24/2017 to 3/31/2019. The dataset comprises of title, issue date, and published state for each article. In addition, the contents of the article (the main text) was parsed for the news articles from California and Kentucky [18].

We subdivided our research questions into two sections, leveraging both quantitative and qualitative methods.

In the first and second questions related to modeling the hepatitis A outbreak, we address the estimation of the percentage of the susceptible population that should be vaccinated to stop the outbreak. Our method includes the application of the IDEA model as well as a non-linear optimization procedure.

The Incidence Decay and Exponential Adjustment (IDEA) model is a single-equation model used for short-term epidemiological forecasting. It depends on two parameters: the basic reproduction number R0 and a discounting factor d, which has a dampening effect similar to analogous financial representations.

The basic reproduction number R0 represents the number of successful transmissions per infected person when she first enters a completely susceptible population and describes initial exponential growth of an outbreak. The rate of growth of an epidemic is a function of both R0 and the average serial interval, defined as the time between symptoms developing in a primary case and symptoms developing in a secondary case. The IDEA model is used to project the growth of outbreaks using only basic epidemiological information such as incidence counts collected on a daily or weekly basis (from serial interval t=0 to T). The formula below relates the total number of cases over time or cumulative incidence to R0 and d. Note that it is appropriate to use the parametric IDEA model when R0 is reasonably low (less than 5) [19].

We investigated the literature and discovered two reported values for hepatitis A serial intervals - 20 days and 27.5 days [20, 21]. Taking in account that CDC WONDER provides weekly reports, we chose 3 weeks (21 days) and 4 weeks (28 days) as the serial intervals for our model and the closest values to those described in the literature.

In order to calibrate the values of the two-parameter IDEA model, we fitted the theoretical representation to empirical data for both California and Kentucky. We leveraged Python SciPy optimization package, more specifically the curve fit method.

The ultimate goal of our research is to quantify (with uncertainty) the fraction of the susceptible population that needs to be vaccinated to curve the hepatitis A outbreak. It is also of interest to us to determine how it compares to the current state of vaccination efforts.

Thanks to the third research question, additional insights were revealed from the unstructured dataset. We applied a sentiment analysis approach. The sentiment analysis is a type of data mining that measures the inclination of people’s opinions through natural language processing (NLP), computational linguistics and text analysis, which are used to extract and analyze subjective information from the Web — mostly social media and similar sources. The analyzed data quantifies the general public’s sentiments or reactions toward certain products, people or ideas and reveal the contextual polarity of the information. Sentiment analysis is also known as opinion mining. More specifically, we used a Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK). NLTK is a leading platform for building Python programs to work with human language data. It provides easy-to-use interfaces to over 50 corpora and lexical resources such as WordNet, along with a suite of text processing libraries for classification, tokenization, stemming, tagging, parsing, and wrappers for industrial-strength NLP libraries.

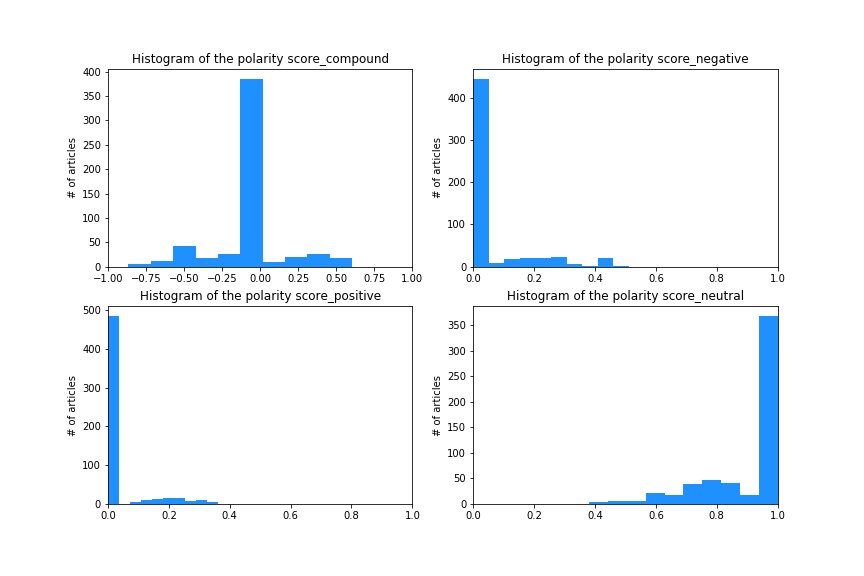

The title of all articles (across all states) were utilized for the sentiment analysis. Four kinds of polarity scores were computed using the NLTK Library (Natural Language Toolkit Library, https://www.nltk.org/). Each word in a bag of words are tagged with a part-of-speech tagger, and then four kinds of polarity scores (positive, negative, neutral and compound) are computed based on the tags. Positive, negative, and neutral scores represent how positive/negative/neutral the input document is (0 ~ 1). The compund score is an aggregated score computed using the three base scores, varying between -1 and +1. Therefore, for each article, four features were computed in total: positive (0 ~ 1), negative (0 ~ 1), neutral (0 ~ 1), and compound (-1 ~ 1).

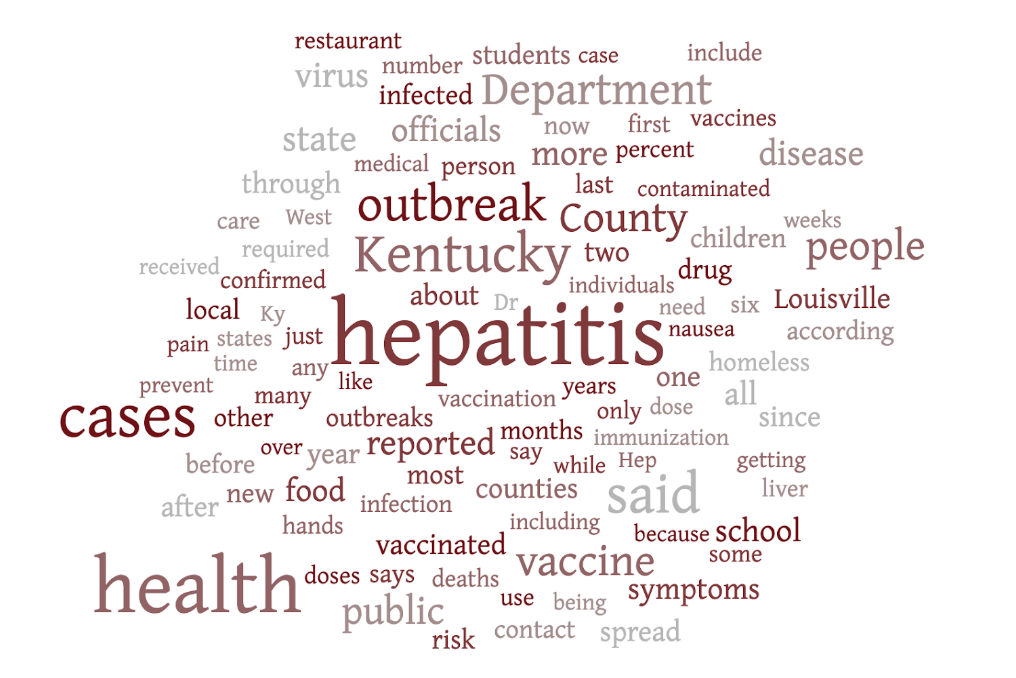

For the word cloud visualization, the actual article contents from California and Kentucky were utilized. Prior to producing the wordcloud visualizaion, stopwords were removed from the data. Then the words that appeared more than 13 times were plotted, and the size is proportional to the log of its occurance.

The performance of our procedure is quite good for both states when using traditional data, as measured here by the Mean Absolute Error or MAE in the figure below. But the calibration performance actually depends on the serial interval value - which again is the time between successive cases in a chain of transmission. As mentioned earlier, we investigated the epidemiology literature which recommended a period of three to four weeks. So we further assessed the sensitivity of our calibration to this sampling choice, using in turn a serial interval of three and four. The results align well, since the MAE is not significantly different from one scenario to another.

Unlike the CDC-reported number of cases, the cumulative incidence extracted from news articles suffers from missing data. There are several ways to handle this: (1) we can use forward filling and carry the most recent value or (2) we can leverage a linear smoothing procedure. In this work, we report results using both methods. They lead to very similar outcomes.

Results of the calibration procedure using carry forward (1) can be found below.

Results of the calibration procedure using linear smoothing (2) can be found below.

Below, we summarize calibration results for both California and Kentucky. The confidence intervals correspond to variations in the serial intervla value.

The reason why we need to have confidence in the calibration of both R0 and d is that ultimately these fitted parameters are used for the assessment of vaccination needs.

We used a method similar to the one described in [12].

We further estimated the vaccination ratio to 15% for Kentucky and found that at least 34% of the susceptible Californian population needed to receive a shot. Our framework is flexible enough to be extended to the 18 other states now affected by the outbreak.

In the case of the hepatitis A outbreak, there has been a vaccine since 1996 and its efficacy is known. The CDC reports an efficacy rate of 95% among adults [22]. We found other literature mentions recommending to use 90% [20,23]. We decided to estimate vaccination needs as a function of efficacy rate, making it vary between 90% and 100%. The following were calculated in the case of California: (1) the fraction VTh of the population that needs to be vaccinated to curb the outbreak, and (2) the percentage V of the susceptible population that has already been vaccinated.

For the former, we borrowed the framework described in [24] and used the below formula. The value for Robs results from our calibration procedure.

For the latter, we found historical values of R0 in the literature and assessed the sensitivity of our estimation using R0 = 1.8 and R0 = 2.1. The vlaue for Robs results from our calibration procedure. The formula is as follows:

A compilation of our results can be found on the graph below.

The graph below shows the distribution of the number of news articles featuring Hepatitis A outbreak across states in the United States. The yellow bars represent the states where the Hepatitis A outbreak was occurred and the green bars represent the complement. The top three states are Kentucky, Michigan and California, all of which had to go through a Hepatitis A outbreak during 2017-2019. One important thing to notice is that there are states with substantially small number of publications even though they had an outbreak. For example, some of the affected states such as Virgina, New Mexico and New Hampshire had a smaller number of news publications than the states where the outbreak has not occurred. If we were to build a model for New Hampshire using this HealthMap article data, there would be not enough datapoints to produce time-series analysis. This shows one of the drawbacks of non-traditional dataset, that the size of the dataset does not commensurates to the actual outbreak.

Remind that we will take a qualitative approach in this section, and the goal is to obtain as much auxillary insight as possible from the dataset that we could model the Hepatitis A outbreak from the previous sections.

The overall trend of the four polarity scores is shown below. All histograms show that most of the articles are neutral, which is expected in the news articles delivering health information.

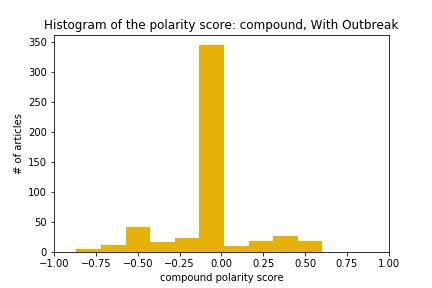

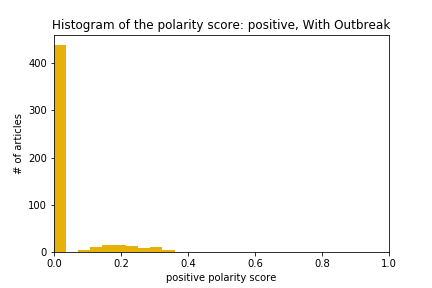

The histograms below shows the four polarity scores of the news titles from the states with and without the Hepatitis A outbreak. Looking at the compound polarity score, most of the articles are delivering messages in a neutral tone, which is natural for a health-related informative news. Even though we cannot quantitatively draw a conclusion, we can see that there are more non-neutral, nuanced articles in the states with outbreak. We believe that this can suggest interesting research questions for epidemiologists.

| States With Outbreak | States Without Outbreak |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Following two figures are the wordcloud of all words contained in the main text of news articles featuring Hepatitis A outbreak from California and Kentucky, respectively. The words in Kentucky side is what one can expect from Hepatitis A outbreak articles. On the other hand, the words in California one show that the media is making connections between Hepatitis A and homeless people. From the same dataset we used to model the outbreak, this simple data visualization captured insights that can guide us in the next step when we want to inform the policymakers.

| California | Kentucky |

|---|---|

|

|

California represents an extreme situation with homelessness - high density of homeless population and the rapid spread. So, the required vaccination percentage for other states would likely be less than 34%.

We assessed our model in different perspectives and showed that the non-traditional data can be a good proxy.

Finally, taking a qualitative approach with the same dataset, we could extract some more insights that can be utilized in policy making process. The sentiment analysis and the word cloud visualization were conducted to show auxiliary information that can be obtained from the non-traditional data. The sentiment analysis suggested how the media is featuring the outbreak in different states, and the wordcloud revealed the connection between the Hepatitis A outbreak and homeless population in California. More approaches to capture the qualitative meaning from the data will be a good research question for the future.

- Koenig KL, Shastry S, Burns MJ. Hepatitis A virus: Essential knowledge and a novel Identify-Isolate-Inform tool for frontline healthcare providers. West J Emerg Med. 2017 Oct;18(6):1000-1007.

- Campos-Outcalt D. CDC provides advice on recent hepatitis A outbreaks J Fam Pract. 2018 January;67(1):30-32.

- CDC. Viral hepatitis surveillance, United States 2016. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2017.

- Health Alert Network (HAN) No.412. Outbreak of Hepatitis A Virus (HAV) Infections among Persons Who Use Drugs and Persons Experiencing Homelessness. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00412.asp

- Latash J, Dorsinville M, Del Rosso P, et al. Notes from the Field: Increase in Reported Hepatitis A Infections Among Men Who Have Sex with Men — New York City, January–August 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:999–1000.

- Foster M, Ramachandran S, Myatt K, et al. Hepatitis A Virus Outbreaks Associated with Drug Use and Homelessness — California, Kentucky, Michigan, and Utah, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1208–1210.

- Kreshak AA, Brennan JJ, Vilke GM et al. A description of a health system's emergency department patients who were part of a large hepatitis A outbreak. J Emerg Med. 2018, Nov; 5(55):620-626.

- Outbreaks of hepatitis A in multiple states among people who use drugs and/or people experiencing homelessness https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/2017March-HepatitisA.htm (Accessed on May 19, 2019).

- Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services. Hepatitis A outbreak. https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/dph/dehp/idb/Pages/hepAoutbreak.aspx (Accessed on May 19, 2019).

- Majumder MS, Kluberg S, Santillana M, Mekaru S, Brownstein JS. 2014 Ebola Outbreak: Media Events Track Changes in Observed Reproductive Number. PLoS Curr. 2015 April 28; 7.

- Ghosh, S. et al. Temporal topic modeling to assess associations between news trends and infectious disease outbreaks. Sci. Rep. 7, 40841.

- Majumder MS, Santillana M, Mekaru SR, McGinnis DP, Khan K, Brownstein JS. Utilizing nontraditional data sources for near real-time estimation of transmission dynamics during the 2015-2016 Colombian Zika virus disease outbreak. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016;2(1):e30

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Estimates of Homelessness. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/estimates-of-homelessness/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- Kushel M. Hepatitis A Outbreak in California — Addressing the Root Cause. N Engl J Med. 2018, Jan; 1(347):3.

- CDC. Vulnerable Counties and Jurisdictions Experiencing or At-Risk of Outbreaks. https://www.cdc.gov/pwid/vulnerable-counties-data.html

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Status Indicators. Opiod overdose deaths. https://www.kff.org/state-category/health-status/opioids/

- CDC WONDER. https://wonder.cdc.gov/nndss/nndss_weekly_tables_menu.asp

- HealthMap. https://healthmap.org/en/

- David N. Fisman , Tanya S. Hauck, Ashleigh R. Tuite, Amy L. Greer. An IDEA for Short Term Outbreak Projection: Nearcasting Using the Basic Reproduction Number. PLOS One. December 31, 2013.

- Zhang X-S, Iacono GL. Estimating human-to-human transmissibility of hepatitis A virus in an outbreak at an elementary school in China, 2011. PLoS ONE 2018 13(9): e0204201.

- Marinovic AB, Swaan C, van Steenbergen J, Kretzshmar M. Quantifying Reporting Timeliness to Improve Outbreak Control. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Feb;21(2):209-16.

- Immunology and Vaccine-Preventable Diseases - Pink Book - Hepatitis A. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/hepa.pdf

- Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bulletin of the World Health Organization (WHO). https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/2/07-040089/en/

- Majumder MS, Nguyen CM, Mekaru SR, Brownstein JS. Yellow fever vaccination coverage heterogeneities in Luanda province, Angola. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Sep;16(9):993-995.