What happens behind the scenes when we type google.com in a browser?

Table of Contents

- Google's 'g' key is pressed

- When you hit 'Enter'

- Parse the URL

- Check HSTS list (deprecated)

- DNS lookup

- Opening of a socket + TLS handshake

- HTTP protocol

- HTTP Server Request Handle

- Server Response

- Behind the scenes of the Browser

- The browser's high level structure

- Rendering Engine

- The Main flow

- Parsing Basics

- DOM Tree

- Render Tree

- Render tree's relation to the DOM tree

- CSS Parsing

- Layout

- Painting

- Trivia

When you just press "g", the browser receives the event and the entire auto-complete machinery kicks into high gear. Depending on your browser's algorithm and if you are in private/incognito mode or not various suggestions will be presented to you in the dropbox below the URL bar. Most of these algorithms prioritize results based on search history and bookmarks. You are going to type "google.com" so none of it matters, but a lot of code will run before you get there and the suggestions will be refined with each key press. It may even suggest "google.com" before you type it.

To pick a zero point, let's choose the Enter key on the keyboard hitting the bottom of its range. At this point, an electrical circuit specific to the enter key is closed (either directly or capacitively). This allows a small amount of current to flow into the logic circuitry of the keyboard, which scans the state of each key switch, debounces the electrical noise of the rapid intermittent closure of the switch, and converts it to a keycode integer, in this case 13. The keyboard controller then encodes the keycode for transport to the computer. This is now almost universally over a Universal Serial Bus (USB) or Bluetooth connection.

In the case of the USB keyboard:

- The keycode generated is stored by internal keyboard circuitry memory in a register called "endpoint".

- The host USB controller polls that "endpoint" every ~10ms, so it gets the keycode value stored on it.

- This value goes to the USB SIE (Serial Interface Engine) sent at a maximum speed of 1.5 Mb/s (USB 2.0).

- This serial signal is then decoded at the computer's host USB controller, and interpreted by the computer's Human Interface Device (HID) universal keyboard device driver.

- The value of the key is then passed into the operating system's hardware abstraction layer.

In the case of touch screen keyboards:

- When the user puts their finger on a modern capacitive touch screen, a tiny amount of current gets transferred to the finger. This completes the circuit through the electrostatic field of the conductive layer and creates a voltage drop at that point on the screen. The screen controller then raises an interrupt reporting the coordinate of the 'click'.

- Then the mobile OS notifies the current focused application of a click event in one of its GUI elements (which now is the virtual keyboard application buttons).

- The virtual keyboard can now raise a software interrupt for sending a 'key pressed' message back to the OS.

- This interrupt notifies the current focused application of a 'key pressed' event.

The browser now has the following information contained in the URL (Uniform Resource Locator):

- Protocol "http": Use 'Hyper Text Transfer Protocol'

- Resource "/": Retrieve main (index) page

When no protocol or valid domain name is given the browser proceeds to feed the text given in the address box to the browser's default web search engine.

The browser checks its "preloaded HSTS (HTTP Strict Transport Security)" list. This is a list of websites that have requested to be contacted via HTTPS only.If the website is in the list, the browser sends its request via HTTPS instead of HTTP. Otherwise, the initial request is sent via HTTP.

Note: The website can still use the HSTS policy without being in the HSTS list. The first HTTP request to the website by a user will receive a response requesting that the user only send HTTPS requests. However, this single HTTP request could potentially leave the user vulnerable to a downgrade attack, which is why the HSTS list is included in modern web browsers.

Modern browsers requests https first

The browser tries to figure out the IP address for the entered domain. The DNS lookup proceeds as follows:

- Browser cache: The browser caches DNS records for some time. Interestingly, the OS does not tell the browser the time-to-live for each DNS record, and so the browser caches them for a fixed duration (varies between browsers, 2 – 30 minutes).

- OS cache: If the browser cache does not contain the desired record, the browser makes a system call (gethostbyname in Windows). The OS has its own cache.

- Router cache: The request continues on to your router, which typically has its own DNS cache.

- ISP DNS cache: The next place checked is the cache ISP’s DNS server. With a cache, naturally.

- Recursive search: Your ISP’s DNS server begins a recursive search, from the root nameserver, through the .com top-level nameserver, to Google’s nameserver. Normally, the DNS server will have names of the .com nameservers in cache, and so a hit to the root nameserver will not be necessary.

Here is a diagram of what a recursive DNS search looks like:

One worrying thing about DNS is that the entire domain like wikipedia.org or facebook.com seems to map to a single IP address. Fortunately, there are ways of mitigating the bottleneck:

- Round-robin DNS is a solution where the DNS lookup returns multiple IP addresses, rather than just one. For example, facebook.com actually maps to four IP addresses.

- Load-balancer is the piece of hardware that listens on a particular IP address and forwards the requests to other servers. Major sites will typically use expensive high-performance load balancers.

- Geographic DNS improves scalability by mapping a domain name to different IP addresses, depending on the client’s geographic location. This is great for hosting static content so that different servers don’t have to update shared state.

- Anycast is a routing technique where a single IP address maps to multiple physical servers. Unfortunately, anycast does not fit well with TCP and is rarely used in that scenario.

Most of the DNS servers themselves use anycast to achieve high availability and low latency of the DNS lookups. Users of an anycast service (DNS is an excellent example) will always connect to the 'closest' (from a routing protocol perspective) DNS server. This reduces latency, as well as providing a level of load-balancing (assuming that your consumers are evenly distributed around your network).

- Once the browser receives the IP address of the destination server, it takes that and the given port number from the URL (the HTTP protocol defaults to port 80, and HTTPS to port 443), and makes a call to the system library function named socket and requests a TCP socket stream.

- The client computer sends a ClientHello message to the server with its TLS version, list of cipher algorithms and compression methods available.

- The server replies with a ServerHello message to the client with the TLS version, selected cipher, selected compression methods and the server's public certificate signed by a CA (Certificate Authority). The certificate contains a public key that will be used by the client to encrypt the rest of the handshake until a symmetric key can be agreed upon.

- The client verifies the server digital certificate against its list of trusted CAs. If trust can be established based on the CA, the client generates a string of pseudo-random bytes and encrypts this with the server's public key. These random bytes can be used to determine the symmetric key.

- The server decrypts the random bytes using its private key and uses these bytes to generate its own copy of the symmetric master key.

- The client sends a Finished message to the server, encrypting a hash of the transmission up to this point with the symmetric key.

- The server generates its own hash, and then decrypts the client-sent hash to verify that it matches. If it does, it sends its own Finished message to the client, also encrypted with the symmetric key.

- From now on the TLS session transmits the application (HTTP) data encrypted with the agreed symmetric key.

You can be pretty sure that dynamic sites such as Facebook/Gmail will not be served from the browser cache because dynamic pages expire either very quickly or immediately (expiry date set to past).

If the web browser used was written by Google, instead of sending an HTTP request to retrieve the page, it will send a request to try and negotiate with the server an "upgrade" from HTTP to the SPDY protocol. Note that SPDY is being deprecated in favor of HTTP/2 in latest versions of Chrome.

GET http://www.google.com/ HTTP/1.1

Accept: application/x-ms-application, image/jpeg, application/xaml+xml, [...]

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; [...]

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: Keep-Alive

Host: google.com

Cookie: datr=1265876274-[...]; locale=en_US; lsd=WW[...]; c_user=2101[...]The GET request names the URL to fetch: “http://www.google.com/”. The browser identifies itself (User-Agent header), and states what types of responses it will accept (Accept and Accept-Encoding headers). The Connection header asks the server to keep the TCP connection open for further requests.

The request also contains the cookies that the browser has for this domain. As you probably already know, cookies are key-value pairs that track the state of a web site in between different page requests. And so the cookies store the name of the logged-in user, a secret number that was assigned to the user by the server, some of user’s settings, etc. The cookies will be stored in a text file on the client, and sent to the server with every request.

HTTP/1.1 defines the "close" connection option for the sender to signal that the connection will be closed after completion of the response. For example, Connection: close.

After sending the request and headers, the web browser sends a single blank newline to the server indicating that the content of the request is done. The server responds with a response code denoting the status of the request and responds with a response of the form: 200 OK [response headers]

Followed by a single newline, and then sends a payload of the HTML content of www.google.com. The server may then either close the connection, or if headers sent by the client requested it, keep the connection open to be reused for further requests.

If the HTTP headers sent by the web browser included sufficient information for the web server to determine if the version of the file cached by the web browser has been unmodified since the last retrieval (ie. if the web browser included an ETag header), it may instead respond with a request of the form: 304 Not Modified [response headers] and no payload, and the web browser instead retrieves the HTML from its cache.

After parsing the HTML, the web browser (and server) repeats this process for every resource (image, CSS, favicon.ico, etc) referenced by the HTML page, except instead of GET / HTTP/1.1 the request will be GET /$(URL relative to www.google.com) HTTP/1.1.

If the HTML referenced a resource on a different domain than www.google.com, the web browser goes back to the steps involved in resolving the other domain, and follows all steps up to this point for that domain. The Host header in the request will be set to the appropriate server name instead of google.com.

Gotcha:

- The trailing slash in the URL “http://facebook.com/” is important. In this case, the browser can safely add the slash. For URLs of the form http://example.com/folderOrFile, the browser cannot automatically add a slash, because it is not clear whether folderOrFile is a folder or a file. In such cases, the browser will visit the URL without the slash, and the server will respond with a redirect, resulting in an unnecessary roundtrip.

- The server might respond with a 301 Moved Permanently response to tell the browser to go to “http://www.google.com/” instead of “http://google.com/”. There are interesting reasons why the server insists on the redirect instead of immediately responding with the web page that the user wants to see. One reason has to do with search engine rankings. See, if there are two URLs for the same page, say http://www.vasanth.com/ and http://vasanth.com/, search engines may consider them to be two different sites, each with fewer incoming links and thus a lower ranking. Search engines understand permanent redirects (301), and will combine the incoming links from both sources into a single ranking. Also, multiple URLs for the same content are not cache-friendly. When a piece of content has multiple names, it will potentially appear multiple times in caches.

Note: HTTP response starts with the returned status code from the server. Following is a very brief summary of what a status code denotes:

- 1xx indicates an informational message only

- 2xx indicates success of some kind

- 3xx redirects the client to another URL

- 4xx indicates an error on the client's part

- 5xx indicates an error on the server's part

The HTTPD (HTTP Daemon) server is the one handling the requests/responses on the server side. The most common HTTPD servers are Apache or nginx for Linux and IIS for Windows.

-

The HTTPD (HTTP Daemon) receives the request.

-

The server breaks down the request to the following parameters:

- HTTP Request Method (either GET, POST, HEAD, PUT and DELETE). In the case of a URL entered directly into the address bar, this will be GET.

- Domain, in this case - google.com.

- Requested path/page, in this case - / (as no specific path/page was requested, / is the default path).

- The server verifies that there is a Virtual Host configured on the server that corresponds with google.com.

-

The server verifies that google.com can accept GET requests.

-

The server verifies that the client is allowed to use this method (by IP, authentication, etc.).

-

If the server has a rewrite module installed (like mod_rewrite for Apache or URL Rewrite for IIS), it tries to match the request against one of the configured rules. If a matching rule is found, the server uses that rule to rewrite the request.

-

The server goes to pull the content that corresponds with the request, in our case it will fall back to the index file, as "/" is the main file (some cases can override this, but this is the most common method).

-

The server parses the file according to the request handler. A request handler is a program (in ASP.NET, PHP, Ruby, …) that reads the request and generates the HTML for the response. If Google is running on PHP, the server uses PHP to interpret the index file, and streams the output to the client.

Note: One interesting difficulty that every dynamic website faces is how to store data. Smaller sites will often have a single SQL database to store their data, but sites that store a large amount of data and/or have many visitors have to find a way to split the database across multiple machines. Solutions include sharding (splitting up a table across multiple databases based on the primary key), replication, and usage of simplified databases with weakened consistency semantics.

Here is the response that the server generated and sent back:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Cache-Control: private, no-store, no-cache, must-revalidate, post-check=0,

pre-check=0

Expires: Sat, 01 Jan 2000 00:00:00 GMT

P3P: CP="DSP LAW"

Pragma: no-cache

Content-Encoding: gzip

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

X-Cnection: close

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Date: Fri, 12 Feb 2010 09:05:55 GMT

2b3

��������T�n�@����[...]The entire response is 36 kB, the bulk of them in the byte blob at the end that I trimmed.

The Content-Encoding header tells the browser that the response body is compressed using the gzip algorithm. After decompressing the blob, you’ll see the HTML you’d expect:

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd">

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xml:lang="en"

lang="en" id="google" class=" no_js">

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<meta http-equiv="Content-language" content="en" />

...Notice the header that sets Content-Type to text/html. The header instructs the browser to render the response content as HTML, instead of say downloading it as a file. The browser will use the header to decide how to interpret the response, but will consider other factors as well, such as the extension of the URL.

Once the server supplies the resources (HTML, CSS, JS, images, etc.) to the browser it undergoes the below process:

- Parsing - HTML, CSS, JS

- Rendering - Construct DOM Tree → Render Tree → Layout of Render Tree → Painting the render tree

-

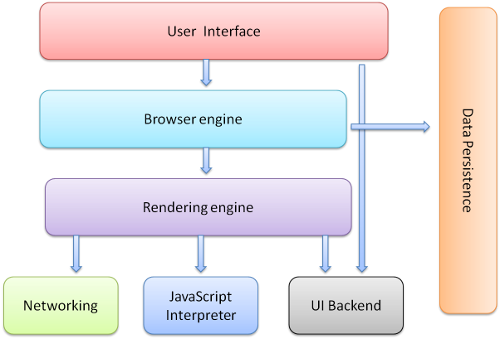

User Interface: Includes the address bar, back/forward button, bookmarking menu, etc. Every part of the browser display except the window where you see the requested page.

-

Browser Engine: Marshals actions between the UI and the rendering engine.

-

Rendering Engine: Responsible for displaying requested content. For eg. the rendering engine parses HTML and CSS, and displays the parsed content on the screen.

-

Networking: For network calls such as HTTP requests, using different implementations for different platforms (behind a platform-independent interface).

-

UI Backend: Used for drawing basic widgets like combo boxes and windows. This backend exposes a generic interface that is not platform specific. Underneath it uses operating system user interface methods.

-

JavaScript Engine: Interpreter used to parse and execute JavaScript code.

-

Data Storage: This is a persistence layer. The browser may need to save data locally, such as cookies. Browsers also support storage mechanisms such as localStorage, IndexedDB and FileSystem.

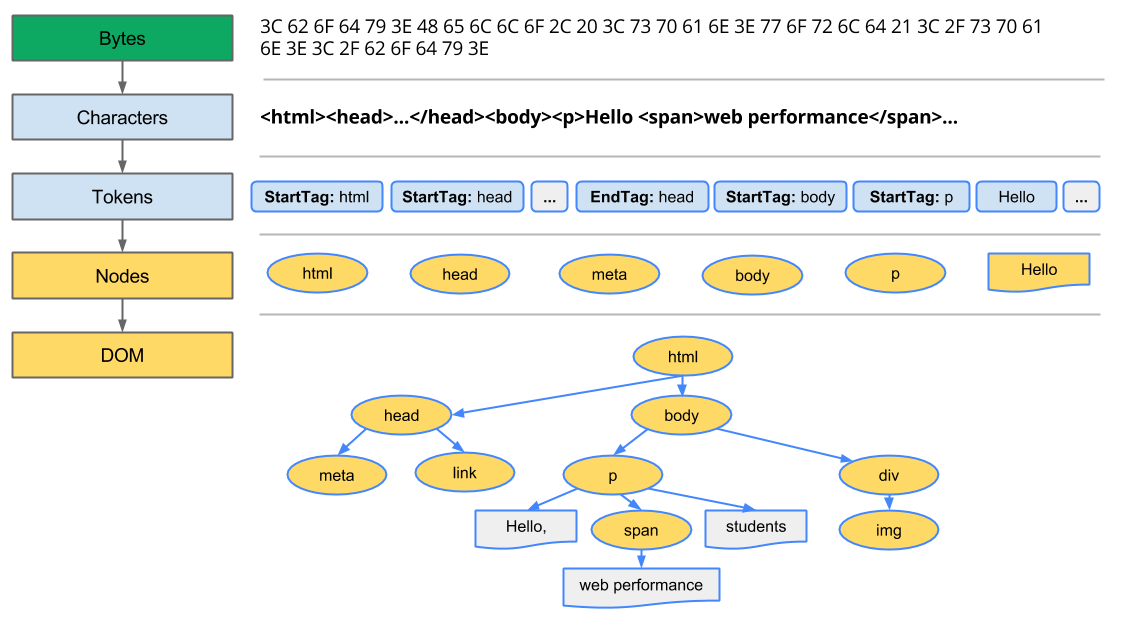

Let’s start, with the simplest possible case: a plain HTML page with some text and a single image. What does the browser need to do to process this simple page?

-

Conversion: the browser reads the raw bytes of the HTML off the disk or network and translates them to individual characters based on specified encoding of the file (e.g. UTF-8).

-

Tokenizing: the browser converts strings of characters into distinct tokens specified by the W3C HTML5 standard - e.g. “”, “” and other strings within the “angle brackets”. Each token has a special meaning and a set of rules.

-

Lexing: the emitted tokens are converted into “objects” which define their properties and rules.

-

DOM construction: Finally, because the HTML markup defines relationships between different tags (some tags are contained within tags) the created objects are linked in a tree data structure that also captures the parent-child relationships defined in the original markup: HTML object is a parent of the body object, the body is a parent of the paragraph object, and so on.

The final output of this entire process is the Document Object Model, or the “DOM” of our simple page, which the browser uses for all further processing of the page.

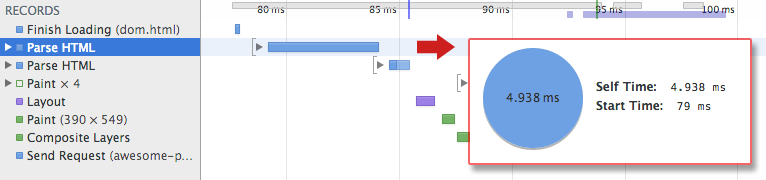

Every time the browser has to process HTML markup it has to step through all of the steps above: convert bytes to characters, identify tokens, convert tokens to nodes, and build the DOM tree. This entire process can take some time, especially if we have a large amount of HTML to process.

If you open up Chrome DevTools and record a timeline while the page is loaded, you can see the actual time taken to perform this step — in the example above, it took us ~5ms to convert a chunk of HTML bytes into a DOM tree. Of course, if the page was larger, as most pages are, this process might take significantly longer. You will see in our future sections on creating smooth animations that this can easily become your bottleneck if the browser has to process large amounts of HTML.

A rendering engine is a software component that takes marked up content (such as HTML, XML, image files, etc.) and formatting information (such as CSS, XSL, etc.) and displays the formatted content on the screen.

| Browser | Engine |

|---|---|

| Chrome | Blink (a fork of WebKit) |

| Firefox | Gecko |

| Safari | Webkit |

| Opera | Blink (Presto if < v15) |

| Internet Explorer | Trident |

| Edge | Blink (EdgeHTML if < v79) |

WebKit is an open source rendering engine which started as an engine for the Linux platform and was modified by Apple to support Mac and Windows.

The rendering engine is single threaded. Almost everything, except network operations, happens in a single thread. In Firefox and Safari this is the main thread of the browser. In Chrome it's the tab process main thread. Network operations can be performed by several parallel threads. The number of parallel connections is limited (usually 6-13 connections per hostname).

The browser main thread is an event loop. It's an infinite loop that keeps the process alive. It waits for events (like layout and paint events) and processes them.

Note: Browsers such as Chrome run multiple instances of the rendering engine: one for each tab. Each tab runs in a separate process.

The rendering engine will start getting the contents of the requested document from the networking layer. This is usually done in 8KB chunks.

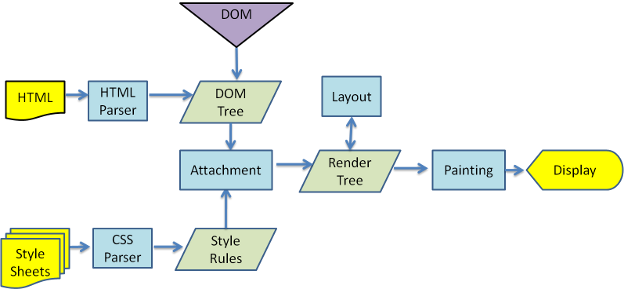

After that the basic flow of the rendering engine is:

The rendering engine will start parsing the HTML document and convert elements to DOM nodes in a tree called the "content tree".

The engine will parse the style data, both in external CSS files and in style elements. Styling information together with visual instructions in the HTML will be used to create another tree: the render tree. The render tree contains rectangles with visual attributes like color and dimensions. The rectangles are in the right order to be displayed on the screen.

After the construction of the render tree it goes through a "layout" process. This means giving each node the exact coordinates where it should appear on the screen.

The next stage is painting-the render tree will be traversed and each node will be painted using the UI backend layer.

It's important to understand that this is a gradual process. For better user experience, the rendering engine will try to display contents on the screen as soon as possible. It will not wait until all HTML is parsed before starting to build and layout the render tree. Parts of the content will be parsed and displayed, while the process continues with the rest of the contents that keeps coming from the network.

Given below is Webkit's flow:

Parsing: Translating the document to a structure the code can use. The result of parsing is usually a tree of nodes that represent the structure of the document.

Grammar: Parsing is based on the syntax rules the document obeys: the language or format it was written in. Every format you can parse must have deterministic grammar consisting of vocabulary and syntax rules. It is called a context free grammar.

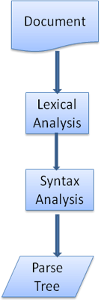

Parsing can be separated into two sub processes: lexical analysis and syntax analysis.

Lexical analysis: The process of breaking the input into tokens. Tokens are the language vocabulary: the collection of valid building blocks.

Syntax analysis: The applying of the language syntax rules.

Parsers usually divide the work between two components: the lexer (sometimes called tokenizer) that is responsible for breaking the input into valid tokens, and the parser that is responsible for constructing the parse tree by analyzing the document structure according to the language syntax rules. The lexer knows how to strip irrelevant characters like white spaces and line breaks.

The parsing process is iterative. The parser will usually ask the lexer for a new token and try to match the token with one of the syntax rules. If a rule is matched, a node corresponding to the token will be added to the parse tree and the parser will ask for another token.

If no rule matches, the parser will store the token internally, and keep asking for tokens until a rule matching all the internally stored tokens is found. If no rule is found then the parser will raise an exception. This means the document was not valid and contained syntax errors.

The job of the HTML parser is to parse the HTML markup into a parse tree. HTML definition is in a DTD (Document Type Definition) format. This format is used to define languages of the SGML family. The format contains definitions for all allowed elements, their attributes and hierarchy. As we saw earlier, the HTML DTD doesn't form a context free grammar.

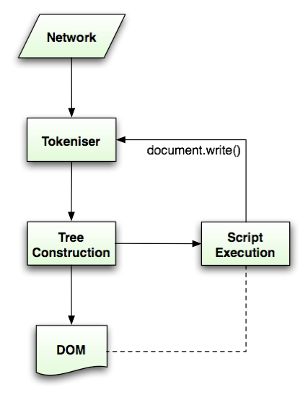

HTML parsing algorithm consists of two stages: tokenization and tree construction.

Tokenization is the lexical analysis, parsing the input into tokens. Among HTML tokens are start tags, end tags, attribute names and attribute values. The tokenizer recognizes the token, gives it to the tree constructor, and consumes the next character for recognizing the next token, and so on until the end of the input.

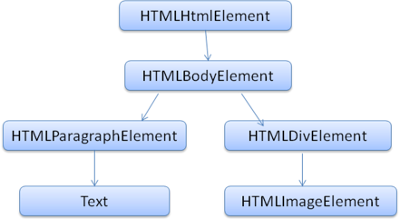

The output tree (the "parse tree") is a tree of DOM element and attribute nodes. DOM is short for Document Object Model. It is the object presentation of the HTML document and the interface of HTML elements to the outside world like JavaScript. The root of the tree is the "Document" object.

The DOM has an almost one-to-one relation to the markup. For example:

<html>

<body>

<p>

Hello World

</p>

<div> <img src="example.png"/></div>

</body>

</html>This markup would be translated to the following DOM tree:

The short answer is that the DOM is not slow. Adding & removing a DOM node is a few pointer swaps, not much more than setting a property on the JS object.

However, layout is slow. When you touch the DOM in any way, you set a dirty bit on the whole tree that tells the browser it needs to figure out where everything goes again. When JS hands control back to the browser, it invokes its layout algorithm (or more technically, it invokes its CSS recalc algorithm, then layout, then repaint, then re-compositing) to redraw the screen. The layout algorithm is quite complex - read the CSS spec to understand some of the rules - and that means it often has to make non-local decisions.

Worse, layout is triggered synchronously by accessing certain properties. Among those are getComputedStyleValue(), getBoundingClientWidth(), .offsetWidth, .offsetHeight, etc, which makes them stupidly easy to run into. Full list is here. Because of this, a lot of Angular and JQuery code is stupidly slow. One layout will blow your entire frame budget on a mobile device. When I measured Google Instant c. 2013, it caused 13 layouts in one query, and locked up the screen for nearly 2 seconds on a mobile device. (It's since been sped up.)

React doesn't help speed up layout - if you want butter-smooth animations on a mobile web browser, you need to resort to other techniques like limiting everything you do in a frame to operations that can be performed on the GPU. But what it does do is ensure that there is at most one layout performed each time you update the state of the page. That's often quite an improvement on the status quo.

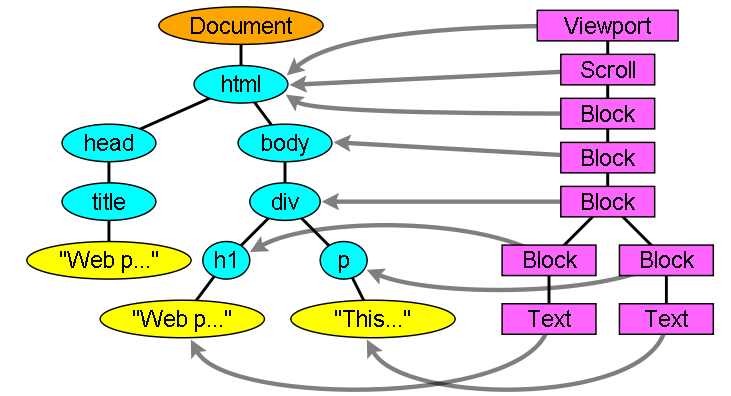

While the DOM tree is being constructed, the browser constructs another tree, the render tree. This tree is of visual elements in the order in which they will be displayed. It is the visual representation of the document. The purpose of this tree is to enable painting the contents in their correct order.

A renderer knows how to lay out and paint itself and its children. Each renderer represents a rectangular area usually corresponding to a node's CSS box.

The renderers correspond to DOM elements, but the relation is not one to one. Non-visual DOM elements will not be inserted in the render tree. An example is the "head" element. Also elements whose display value was assigned to "none" will not appear in the tree (whereas elements with "hidden" visibility will appear in the tree).

There are DOM elements which correspond to several visual objects. These are usually elements with complex structure that cannot be described by a single rectangle. For example, the "select" element has three renderers: one for the display area, one for the drop down list box and one for the button. Also when text is broken into multiple lines because the width is not sufficient for one line, the new lines will be added as extra renderers.

Some render objects correspond to a DOM node but not in the same place in the tree. Floats and absolutely positioned elements are out of flow, placed in a different part of the tree, and mapped to the real frame. A placeholder frame is where they should have been.

In WebKit the process of resolving the style and creating a renderer is called "attachment". Every DOM node has an "attach" method. Attachment is synchronous, node insertion to the DOM tree calls the new node "attach" method.

Building the render tree requires calculating the visual properties of each render object. This is done by calculating the style properties of each element. The style includes style sheets of various origins, inline style elements and visual properties in the HTML (like the "bgcolor" property).The later is translated to matching CSS style properties.

CSS Selectors are matched by browser engines from right to left. Keep in mind that when a browser is doing selector matching it has one element (the one it's trying to determine style for) and all your rules and their selectors and it needs to find which rules match the element. This is different from the usual jQuery thing, say, where you only have one selector and you need to find all the elements that match that selector.

A selector's specificity is calculated as follows:

- Count 1 if the declaration it is from is a 'style' attribute rather than a rule with a selector, 0 otherwise (= a)

- Count the number of ID selectors in the selector (= b)

- Count the number of class selectors, attributes selectors, and pseudo-classes in the selector (= c)

- Count the number of element names and pseudo-elements in the selector (= d)

- Ignore the universal selector

Concatenating the three numbers a-b-c-d (in a number system with a large base) gives the specificity. The number base you need to use is defined by the highest count you have in one of a, b, c and d.

Examples:

* /* a=0 b=0 c=0 -> specificity = 0 */

LI /* a=0 b=0 c=1 -> specificity = 1 */

UL LI /* a=0 b=0 c=2 -> specificity = 2 */

UL OL+LI /* a=0 b=0 c=3 -> specificity = 3 */

H1 + *[REL=up] /* a=0 b=1 c=1 -> specificity = 11 */

UL OL LI.red /* a=0 b=1 c=3 -> specificity = 13 */

LI.red.level /* a=0 b=2 c=1 -> specificity = 21 */

#x34y /* a=1 b=0 c=0 -> specificity = 100 */

#s12:not(FOO) /* a=1 b=0 c=1 -> specificity = 101 */Why does the CSSOM have a tree structure? When computing the final set of styles for any object on the page, the browser starts with the most general rule applicable to that node (e.g. if it is a child of body element, then all body styles apply) and then recursively refines the computed styles by applying more specific rules - i.e. the rules “cascade down”.

WebKit uses a flag that marks if all top level style sheets (including @imports) have been loaded. If the style is not fully loaded when attaching, place holders are used and it is marked in the document, and they will be recalculated once the style sheets were loaded.

When the renderer is created and added to the tree, it does not have a position and size. Calculating these values is called layout or reflow.

HTML uses a flow based layout model, meaning that most of the time it is possible to compute the geometry in a single pass. Elements later 'in the flow' typically do not affect the geometry of elements that are earlier 'in the flow', so layout can proceed left-to-right, top-to-bottom through the document. The coordinate system is relative to the root frame. Top and left coordinates are used.

Layout is a recursive process. It begins at the root renderer, which corresponds to the element of the HTML document. Layout continues recursively through some or all of the frame hierarchy, computing geometric information for each renderer that requires it.

The position of the root renderer is 0,0 and its dimensions are the viewport–the visible part of the browser window. All renderers have a "layout" or "reflow" method, each renderer invokes the layout method of its children that need layout.

In order not to do a full layout for every small change, browsers use a "dirty bit" system. A renderer that is changed or added marks itself and its children as "dirty": needing layout. There are two flags: "dirty", and "children are dirty" which means that although the renderer itself may be OK, it has at least one child that needs a layout.

The layout usually has the following pattern:

- Parent renderer determines its own width.

- Parent goes over children and:

- Place the child renderer (sets its x and y).

- Calls child layout if needed–they are dirty or we are in a global layout, or for some other reason–which calculates the child's height.

- Parent uses children's accumulative heights and the heights of margins and padding to set its own height–this will be used by the parent renderer's parent.

- Sets its dirty bit to false.

Also note, layout thrashing is where a web browser has to reflow or repaint a web page many times before the page is ‘loaded’. In the days before JavaScript’s prevalence, websites were typically reflowed and painted just once, but these days it is increasingly common for JavaScript to run on page load which can cause modifications to the DOM and therefore extra reflows or repaints. Depending on the number of reflows and the complexity of the web page, there is potential to cause significant delay when loading the page, especially on lower powered devices such as mobile phones or tablets.

In the painting stage, the render tree is traversed and the renderer's "paint()" method is called to display content on the screen. Painting uses the UI infrastructure component.

Like layout, painting can also be global–the entire tree is painted–or incremental. In incremental painting, some of the renderers change in a way that does not affect the entire tree. The changed renderer invalidates its rectangle on the screen. This causes the OS to see it as a "dirty region" and generate a "paint" event. The OS does it cleverly and coalesces several regions into one.

Before repainting, WebKit saves the old rectangle as a bitmap. It then paints only the delta between the new and old rectangles. The browsers try to do the minimal possible actions in response to a change. So changes to an element's color will cause only repaint of the element. Changes to the element position will cause layout and repaint of the element, its children and possibly siblings. Adding a DOM node will cause layout and repaint of the node. Major changes, like increasing font size of the "html" element, will cause invalidation of caches, relayout and repaint of the entire tree.

There are three different positioning schemes:

- Normal: the object is positioned according to its place in the document. This means its place in the render tree is like its place in the DOM tree and laid out according to its box type and dimensions

- Float: the object is first laid out like normal flow, then moved as far left or right as possible

- Absolute: the object is put in the render tree in a different place than in the DOM tree

The positioning scheme is set by the "position" property and the "float" attribute.

- static and relative cause a normal flow

- absolute and fixed cause absolute positioning

In static positioning no position is defined and the default positioning is used. In the other schemes, the author specifies the position: top, bottom, left, right.

Layers are specified by the z-index CSS property. It represents the third dimension of the box: its position along the "z axis".

The boxes are divided into stacks (called stacking contexts). In each stack the back elements will be painted first and the forward elements on top, closer to the user. In case of overlap the foremost element will hide the former element. The stacks are ordered according to the z-index property. Boxes with "z-index" property form a local stack.

Tim Berners-Lee, a British scientist at CERN, invented the World Wide Web (WWW) in 1989. The web was originally conceived and developed to meet the demand for automatic information-sharing between scientists in universities and institutes around the world.

The first website at CERN - and in the world - was dedicated to the World Wide Web project itself and was hosted on Berners-Lee's NeXT computer. The website described the basic features of the web; how to access other people's documents and how to set up your own server. The NeXT machine - the original web server - is still at CERN. As part of the project to restore the first website, in 2013 CERN reinstated the world's first website to its original address.

On 30 April 1993, CERN put the World Wide Web software in the public domain. CERN made the next release available with an open license, as a more sure way to maximize its dissemination. Through these actions, making the software required to run a web server freely available, along with a basic browser and a library of code, the web was allowed to flourish.

More reading:

What really happens when you navigate to a URL

How Browsers Work: Behind the scenes of modern web browsers

What exactly happens when you browse a website in your browser?

So how does the browser actually render a website

How the Web Works: A Primer for Newcomers to Web Development (or anyone, really)