Scala.Rx is an experimental change propagation library for Scala. Scala.Rx gives you Reactive variables (Rxs), which are smart variables who auto-update themselves when the values they depend on change. The underlying implementation is push-based FRP based on the ideas in Deprecating the Observer Pattern.

A simple example which demonstrates the behavior is:

import rx._

val a = Var(1); val b = Var(2)

val c = Rx{ a() + b() }

println(c()) // 3

a() = 4

println(c()) // 6The idea being that 99% of the time, when you re-calculate a variable, you re-calculate it the same way you initially calculated it. Furthermore, you only re-calculate it when one of the values it depends on changes. Scala.Rx does this for you automatically, and handles all the tedious update logic for you so you can focus on other, more interesting things!

Apart from basic change-propagation, Scala.Rx provides a host of other functionality, such as a set of combinators for easily constructing the dataflow graph, automatic parallelization of updates, and seamless interop with existing Scala code. This means it can be easily embedded in an existing Scala application.

Scala.Rx is available on Maven Central. In order to get started, simply add the following to your build.sbt:

libraryDependencies += "com.scalarx" %% "scalarx" % "0.2.6"After that, opening up the sbt console and pasting the above example into the console should work! You can proceed through the examples in the Basic Usage page to get a feel for what Scala.Rx can do.

In addition to running on the JVM, Scala.Rx also compiles to Scala-Js! This artifact is currently on Maven Central and an be used via the following SBT snippet:

libraryDependencies += "com.scalarx" %% "scalarx" % "0.2.6"There are some minor differences between running Scala.Rx on the JVM and in Javascript particularly around asynchronous operations, the parallelism model and memory model. In general, though, all the examples given in the documentation below will work perfectly when cross-compiled to javascript and run in the browser!

Scala.rx 0.2.6 is only compatible with ScalaJS 0.5.3+.

The primary operations only need a import rx._ before being used, with addtional operations also needing a import rx.ops._. Some of the examples below also use various imports from scala.concurrent or scalatest aswell.

import rx._

val a = Var(1); val b = Var(2)

val c = Rx{ a() + b() }

println(c()) // 3

a() = 4

println(c()) // 6The above example is an executable program. In general, import rx._ is enough to get you started with Scala.Rx, and it will be assumed in all further examples. These examples are all taken from the unit tests.

The basic entities you have to care about are Var, Rx and Obs:

- Var: a smart variable which you can get using

a()and set usinga() = .... Whenever its value changes, it pings any downstream entity which needs to be recalculated. - Rx: a reactive definition which automatically captures any Vars or other Rxs which get called in its body, flagging them as dependencies and re-calculating whenever one of them changes. Like a Var, you can use the

a()syntax to retrieve its value, and it also pings downstream entities when the value changes. - Obs: an observer on one or more Var s or Rx s, performing some side-effect when the observed node changes value and sends it a ping.

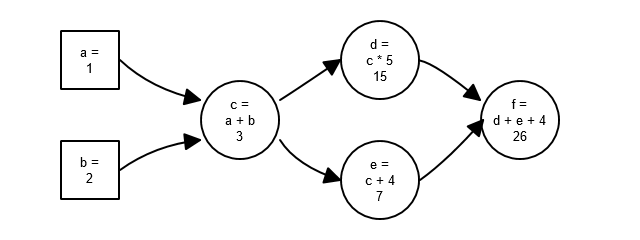

Using these components, you can easily construct a dataflow graph, and have the various values within the dataflow graph be kept up to date when the inputs to the graph change:

val a = Var(1) // 1

val b = Var(2) // 2

val c = Rx{ a() + b() } // 3

val d = Rx{ c() * 5 } // 15

val e = Rx{ c() + 4 } // 7

val f = Rx{ d() + e() + 4 } // 26

println(f()) // 26

a() = 3

println(f()) // 38The dataflow graph for this program looks like this:

Where the Vars are represented by squares, the Rxs by circles and the dependencies by arrows. Each Rx is labelled with its name, its body and its value.

Modifying the value of a causes the changes the propagate through the dataflow graph

As can be seen above, changing the value of a causes the change to propagate all the way through c d e to f. You can use a Var and Rx anywhere you an use a normal variable.

The changes propagate through the dataflow graph in waves. Each update to a Var touches off a propagation, which pushes the changes from that Var to any Rx which is (directly or indirectly) dependent on its value. In the process, it is possible for a Rx to be re-calculated more than once.

###Observers

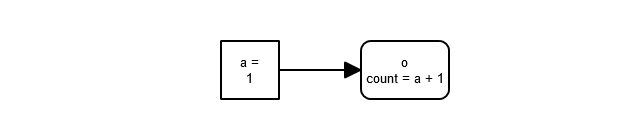

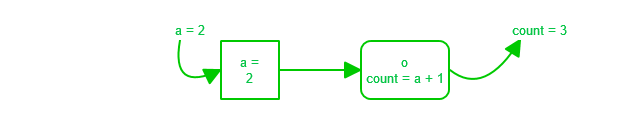

As mentioned, Obs s can be used to observe Rx s and Var s and perform side effects when they change:

val a = Var(1)

var count = 0

val o = Obs(a){

count = a() + 1

}

println(count) // 2

a() = 4

println(count) // 5This creates a dataflow graph that looks like:

When a is modified, the observer o will perform the side effect:

The body of Rxs should be side effect free, as they may be run more than once per propagation. You should use Obss to perform your side effects, as they are guaranteed to run only once per propagation after the values for all Rxs have stabilized.

Scala.Rx provides a convenient .foreach() combinator, which provides an alternate way of creating an Obs from an Rx:

val a = Var(1)

var count = 0

val o = a.foreach{ x =>

count = x + 1

}

println(count) // 2

a() = 4

println(count) // 5This example does the same thing as the code above.

Note that the body of the Obs is run once initially when it is declared. This matches the way each Rx is calculated once when it is initially declared. but it is conceivable that you want an Obs which first for the first time only when the Rx it is listening to changes. You can do this by passing the skipInitial flag when creating it:

val a = Var(1)

var count = 0

val o = Obs(a, skipInitial=true){

count = count + 1

}

println(count) // 0

a() = 2

println(count) // 1An Obs acts to encapsulate the callback that it runs. They can be passed around, stored in variables, etc.. When the Obs gets garbage collected, the callback will stop triggering. Thus, an Obs should be stored in the object it affects: if the callback only affects that object, it doesn't matter when the Obs itself gets garbage collected, as it will only happen after that object holding it becomes unreachable, in which case its effects cannot be observed anyway. An Obs can also be actively shut off, if a stronger guarantee is needed:

val a = Var(1)

val b = Rx{ 2 * a() }

var target = 0

val o = Obs(b){

target = b()

}

println(target) // 2

a() = 2

println(target) // 4

o.kill()

a() = 3

println(target) // 4After manually setting active = false, the Obs no longer triggers. Apart from .kill()ing Obss, you can also kill Rxs, which prevents further updates. Rxs also have a .killAll() method, which kills the Rx together with all its descendents, useful if you decide a whole section of the graph ought to be shut off.

In general, Scala.Rx revolves around constructing dataflow graphs which automatically keep things in sync, which you can easily interact with from external, imperative code. This involves using:

- Vars as inputs to the dataflow graph from the imperative world

- Rxs as the intermediate nodes in the dataflow graphs

- Obss as the output from the dataflow graph to the imperative world

###Complex Reactives

Rxs are not limited to Ints. Strings, Seq[Int]s, Seq[String]s, anything can go inside an Rx:

val a = Var(Seq(1, 2, 3))

val b = Var(3)

val c = Rx{ b() +: a() }

val d = Rx{ c().map("omg" * _) }

val e = Var("wtf")

val f = Rx{ (d() :+ e()).mkString }

println(f()) // "omgomgomgomgomgomgomgomgomgwtf"

a() = Nil

println(f()) // "omgomgomgwtf"

e() = "wtfbbq"

println(f()) // "omgomgomgwtfbbq"As shown, you can use Scala.Rx's reactive variables to model problems of arbitrary complexity, not just trivial ones which involve primitive numbers.

###Error Handling

Since the body of an Rx can be any arbitrary Scala code, it can throw exceptions. Propagating the exception up the call stack would not make much sense, as the code evaluating the Rx is probably not in control of the reason it failed. Instead, any exceptions are caught by the Rx itself and stored internally as a Try.

This can be seen in the following unit test:

val a = Var(1)

val b = Rx{ 1 / a() }

println(b()) // 1

println(b.toTry) // Success(1)

a() = 0

intercept[ArithmeticException]{

b()

}

assert(b.toTry.isInstanceOf[Failure])Initially, the value of a is 1 and so the value of b also is 1. You can also extract the internal Try using b.toTry, which at first is Success(1).

However, when the value of a becomes 0, the body of b throws an ArithmeticException. This is caught by b and re-thrown if you try to extract the value from b using b(). You can extract the entire Try using toTry and pattern match on it to handle both the Success case as well as the Failure case.

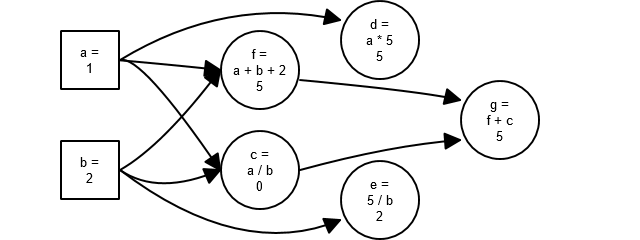

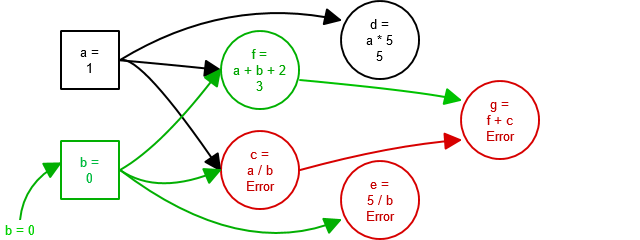

When you have many Rxs chained together, exceptions propagate forward following the dependency graph, as you would expect. The following code:

val a = Var(1)

val b = Var(2)

val c = Rx{ a() / b() }

val d = Rx{ a() * 5 }

val e = Rx{ 5 / b() }

val f = Rx{ a() + b() + 2 }

val g = Rx{ f() + c() }

inside(c.toTry){case Success(0) => () }

inside(d.toTry){case Success(5) => () }

inside(e.toTry){case Success(2) => () }

inside(f.toTry){case Success(5) => () }

inside(g.toTry){case Success(5) => () }

b() = 0

inside(c.toTry){case Failure(_) => () }

inside(d.toTry){case Success(5) => () }

inside(e.toTry){case Failure(_) => () }

inside(f.toTry){case Success(3) => () }

inside(g.toTry){case Failure(_) => () }Creates a dependency graph that looks like the follows:

In this example, initially all the values for a, b, c, d, e, f and g are well defined. However, when b is set to 0:

c and e both result in exceptions, and the exception from c propagates to g. Attempting to extract the value from g using g(), for example, will re-throw the ArithmeticException. Again, using toTry works too.

###Nesting

Rxs can contain other Rxs, arbitrarily deeply. This example shows the Rxs nested two levels deep:

val a = Var(1)

val b = Rx{

(Rx{ a() }, Rx{ math.random })

}

val r = b()._2()

a() = 2

println(b()._2()) // rIn this example, we can see that although we modified a, this only affects the left-inner Rx, neither the right-inner Rx (which takes on a different, random value each time it gets re-calculated) or the outer Rx (which would cause the whole thing to re-calculate) are affected. A slightly less contrived example may be:

var fakeTime = 123

trait WebPage{

def fTime = fakeTime

val time = Var(fTime)

def update(): Unit = time() = fTime

val html: Rx[String]

}

class HomePage extends WebPage {

val html = Rx{"Home Page! time: " + time()}

}

class AboutPage extends WebPage {

val html = Rx{"About Me, time: " + time()}

}

val url = Var("www.mysite.com/home")

val page = Rx{

url() match{

case "www.mysite.com/home" => new HomePage()

case "www.mysite.com/about" => new AboutPage()

}

}

println(page().html()) // "Home Page! time: 123"

fakeTime = 234

page().update()

println(page().html()) // "Home Page! time: 234"

fakeTime = 345

url() = "www.mysite.com/about"

println(page().html()) // "About Me, time: 345"

fakeTime = 456

page().update()

println(page().html()) // "About Me, time: 456"In this case, we define a web page which has a html value (a Rx[String]). However, depending on the url, it could be either a HomePage or an AboutPage, and so our page object is a Rx[WebPage].

Having a Rx[WebPage], where the WebPage has an Rx[String] inside, seems natural and obvious, and Scala.Rx lets you do it simply and naturally. This kind of objects-within-objects situation arises very naturally when modelling a problem in an object-oriented way. The ability of Scala.Rx to gracefully handle the corresponding Rxs within Rxs allows it to gracefully fit into this paradigm, something I found lacking in most of the Related Work I surveyed.

Most of the examples here are taken from the unit tests, which provide more examples on guidance on how to use this library.

Apart from the basic building blocks of Var/Rx/Obs, Scala.Rx also provides a set of combinators which allow your to easily transform your Rxs; this allows the programmer to avoid constantly re-writing logic for the common ways of constructing the dataflow graph. The three basic combinators: map(), filter() and reduce() are modelled after the scala collections library, and provide an easy way of transforming the values coming out of a Rx.

###Map

val a = Var(10)

val b = Rx{ a() + 2 }

val c = a.map(_*2)

val d = b.map(_+3)

println(c()) // 20

println(d()) // 15

a() = 1

println(c()) // 2

println(d()) // 6map does what you would expect, creating a new Rx with the value of the old Rx transformed by some function. For example, a.map(_*2) is essentially equivalent to Rx{ a() * 2 }, but somewhat more convenient to write.

###Filter

val a = Var(10)

val b = a.filter(_ > 5)

a() = 1

println(b()) // 10

a() = 6

println(b()) // 6

a() = 2

println(b()) // 6

a() = 19

println(b()) // 19filter ignores changes to the value of the Rx that fail the predicate.

Note that none of the filter methods is able to filter out the first, initial value of a Rx, as there is no "older" value to fall back to. Hence this:

val a = Var(2)

val b = a.filter(_ > 5)

println(b())will print out "2".

###Reduce

val a = Var(1)

val b = a.reduce(_ * _)

a() = 2

println(b()) // 2

a() = 3

println(b()) // 6

a() = 4

println(b()) // 24The reduce operator combines subsequent values of an Rx together, starting from the initial value. Every change to the original Rx is combined with the previously-stored value and becomes the new value of the reduced Rx.

Each of these three combinators has a counterpart in mapAll(), filterAll() and reduceAll() which operates on Try[T]s rather than Ts, in the case where you need the added flexibility to handle Failures in some special way.

These are combinators which do more than simply transforming a value from one to another. These have asynchronous effects, and can spontaneously modify the dataflow graph and begin propagation cycles without any external trigger. Although this may sound somewhat unsettling, the functionality provided by these combinators is often necessary, and manually writing the logic around something like Debouncing, for example, is far more error prone than simply using the combinators provided.

Note that none of these combinators are doing anything that cannot be done via a combination of Obss and Vars; they simply encapsulate the common patterns, saving you manually writing them over and over, and reducing the potential for bugs.

###Async

import scala.concurrent.Promise

import scala.concurrent.ExecutionContext.Implicits.global

val p = Promise[Int]()

val a = Rx{

p.future

}.async(10)

println(a()) // 10

p.success(5)

println(a()) // 5The async combinator only applies to Rx[Future[_]]s. It takes an initial value, which will be the value of the Rx until the Future completes, at which point the the value will become the value of the Future.

async can create Futures as many times as necessary. This example shows it creating two distinct Futures:

import scala.concurrent.Promise

import scala.concurrent.ExecutionContext.Implicits.global

var p = Promise[Int]()

val a = Var(1)

val b = Rx{

val A = a()

p.future.map{_ + A}

}.async(10)

println(b()) // 10

p.success(5)

println(b()) // 6

p = Promise[Int]()

a() = 2

println(b()) // 6

p.success(7)

println(b()) // 9The value of b() updates as you would expect as the series of Futures complete (in this case, manually using Promises).

This is handy if your dependency graph contains some asynchronous elements. For example, you could have a Rx which depends on another Rx, but requires an asynchronous web request to calculate its final value. With async, the results from the asynchronous web request will be pushed back into the dataflow graph automatically when the Future completes, starting off another propagation run and conveniently updating the rest of the graph which depends on the new result.

async optionally takes a second argument which causes out-of-order Futures to be dropped. This is useful if you always want to have the result of the most recently-created Future which completed, rather than the most-recently-completed Future.

###Timer

import scala.concurrent.duration._

implicit val scheduler = new AkkaScheduler(akka.actor.ActorSystem())

val t = Timer(100 millis)

var count = 0

val o = Obs(t){

count = count + 1

}

println(count) // 3

println(count) // 8

println(count) // 13A Timer is a Rx that generates events on a regular basis. The events are based on the AkkaScheduler which wraps an ActorSystem when running on the JVM, or a DomScheduler which wraps setTimeout when running on ScalaJS. In the example above, the for-loop checks that the value of the timer t() increases over time from 0 to 5, and then checks that count has been incremented at least that many times.

The scheduled task is cancelled automatically when the Timer object becomes unreachable, so it can be garbage collected. This means you do not have to worry about managing the life-cycle of the Timer. On the other hand, this means the programmer should ensure that the reference to the Timer is held by the same object as that holding any Rx listening to it. This will ensure that the exact moment at which the Timer is garbage collected will not matter, since by then the object holding it (and any Rx it could possibly affect) are both unreachable.

###Delay

import scala.concurrent.duration._

implicit val scheduler = new AkkaScheduler(akka.actor.ActorSystem())

val a = Var(10)

val b = a.delay(250 millis)

a() = 5

println(b()) // 10

eventually{

println(b()) // 5

}

a() = 4

println(b()) // 5

eventually{

println(b()) // 4

}The delay(t) combinator creates a delayed version of an Rx whose value lags the original by a duration t. When the Rx changes, the delayed version will not change until the delay t has passed.

This example shows the delay being applied to a Var, but it could easily be applied to an Rx as well.

###Debounce

import scala.concurrent.duration._

implicit val scheduler = new AkkaScheduler(akka.actor.ActorSystem())

val a = Var(10)

val b = a.debounce(200 millis)

a() = 5

println(b()) // 5

a() = 2

println(b()) // 5

eventually{

println(b()) // 2

}

a() = 1

println(b()) // 2

eventually{

println(b()) // 1

}The debounce(t) combinator creates a version of an Rx which will not update more than once every time period t.

If multiple updates happen with a short span of time (less than t apart), the first update will take place immediately, and a second update will take place only after the time t has passed. For example, this may be used to limit the rate at which an expensive result is re-calculated: you may be willing to let the calculated value be a few seconds stale if it lets you save on performing the expensive calculation more than once every few seconds.

The fact that you can introspect the Scala.Rx dataflow graph means you can find out not just what the current value of any Rx is, but also why its that value. For example, if you take the following graph:

val a = Var(1)

val b = Var(2)

val c = Rx{ a() + b() } // 3

val d = Rx{ c() * 5 } // 15

val e = Rx{ c() + 4 } // 7

val f = Rx{ d() + e() + 4 } // 26We know the value of f is 26:

println(f()) // 26But why is it 26? We can ask it for the value of its parents:

println(f.parents)

// List(rx.core.Dynamic@119e2f23, rx.core.Dynamic@506c0c49)

println(f.parents.collect{case r: Rx[_] => r()})

// List(7, 15)This is interesting, but not that helpful, since the hash of each parent is pretty opaque and the ordering of the parents is arbitrary. However, we can also assign names to these nodes:

val a = Var(1, name="a")

val b = Var(2, name="b")

val c = Rx(name="c"){ a() + b() }

val d = Rx(name="d"){ c() * 5 }

val e = Rx(name="e"){ c() + 4 }

val f = Rx(name="f"){ d() + e() + 4 }Now we can query the graph based on human-readable names, which is a great improvement! For example, here's all the descendents of c:

println(c.descendants.map(_.name)) // List(e, d, f, f)Or the names and values of all the nodes (ancestors) that were used in the computation of f:

f.ancestors

.map{ case r: Rx[_] => r.name + " " + r() }

.foreach(println)

// e 7

// d 15

// c 3

// b 2

// a 1This ability to query the dataflow graph is useful when debugging why things are going wrong and values are not what you think they are.

Scala.Rx is a library, and apart from a single DynamicVariable, maintains no global state. This means that if you use Scala.Rx to build dataflow graphs at different parts of your program, these dataflow graphs will be completely independent and there's no chance of cross-talk or interference between them.

Scala.Rx tracks the dependency graph between different Vars and Rxs without any explicit annotation by the programmer. This means that in (almost) all cases, you can just write your code as if it wasn't being tracked, and Scala.Rx would build up the dependency graph automatically.

Every time the body of an Rx{...} is evaluated (or re-evaluated), it is put into a DynamicVariable. Any calls to the .apply() methods of other Rxs then inspect this DynamicVariable to determine who (if any) is the Rx being evaluated. This is linked up with the Rx whose .apply() is being called, creating a dependency between them. Thus a dependency graph is implicitly created without any action on the part of the programmer.

The dependency-tracking strategy of Scala.Rx is based of a subset of the ideas in Deprecating the Observer Pattern, in particular their definition of "Opaque Signals". The implementation follows it reasonably closely.

###Weak Forward References

Once we have evaluated our Vars and Rxs once and have a dependency graph, how do we keep track of our children (the Rxs who depend on us) and tell them to update? Simply keeping a List() of all children will cause memory leaks, as the List() will prevent any child from being garbage collected even if all other references to the child have been lost and the child is otherwise unaccessible.

Instead, Scala.Rx using a list of WeakReferences. These allow the Rx to keep track of its children while still letting them get garbage collected when all other references to them are lost. When a child becomes unreachable and gets garbage collected, the WeakReference becomes null, and these null references get cleared from the list every time it is updated.

###Propagation Strategies The default propagation of changes is done in a breadth-first, topologically-sorted order, similar to that described in the paper. Each propagation run occurs when a Var is set, e.g. in

val x = Var(0)

val y = Rx(x * 2)

println(y) // 2

x() = 2

println(y) // 4The propagation begins when x is modified via x() = 2, in this case ending at y which updates to the new value 4.

Nodes earlier in the dependency graph are evaluated before those down the line. However, due to the fact that the dependencies of a Rx are not known until it is evaluated, it is impossible to strictly maintain this invariant at all times, since the underlying graph could change unpredictably.

In general, Scala.Rx keeps track of the topological order dynamically, such that after initialization, if the dependency graph does not change too radically, most nodes should be evaluated only once per propagation, but this is not a hard guarantee.

Hence, it is possible that an Rx will get evaluated more than once, even if only a single Var is updated. You should ensure that the body of any Rxs can tolerate being run more than once without harm. If you need to perform side effects, use an Obs, which only executes its side effects once per propagation run after the values for all Rxs have stabilized.

The default propagator (Propagator.Immediate) does this all synchronously: it performs each update one at a time, in the roughly-topological-order described above, and the update function

x() = 2only returns after all updates have completed. This can be changed by creating a new Propagator.ExecContext with a custom ExecutionContext. e.g.:

implicit val propagator = new BreadthFirstPropagator(ExecutionContext.global)

x() = 2In this case, the updating of nodes is farmed out to the given ExecutionContext. Nodes which do not depend on each other may be updated in parallel, if the given ExecutionContext provides parallelism. When using a Propagator.ExecContext, the update method does not block but instead returns a Future[Unit] which can be waited upon for the operation to complete asynchronously.

Even with a custom ExecutionContext, all updates still occur in (roughly) topologically sorted order. If for some reason you do not want this, it is possible to customize this by creating a completely custom Propagator who is responsible for performing these updates. Custom Propagators can also allow you to customize what the update method (e.g. in x() = 2) returns, e.g. if you want to collect additional data related to that propagation.

Note that asynchronous Rxs like those from .async, .delay or .debounce swallow incoming pings and begin a fresh propagation cycle when their asynchronous action triggers.

By default, everything happens on a single-threaded execution context and there is no parallelism. By using a custom Propagator.ExecContext, it is possible to have the updates in each propagation run happen in parallel (though not on ScalaJS. For more information on ExecutionContexts, see the Akka Documentation. The unit tests also contain an example of a dependency graph whose evaluation is spread over multiple threads in this way to provide a performance increase.

Even without using an explicitly parallelizing ExecutionContext, parallelism could creep into your code in subtle ways: a delayed Rx, for example may happen to fire and continue its propagation just as you update a Var somewhere on the same dependency graph, resulting in two propagations proceeding in parallel.

In general, the rules for parallel execution of an individual node in the dependency graph is as follows:

- A Rx can up updated by an arbitrarily high number of parallel threads: make sure your code can handle this!. I will refer to each of these as a parallel update.

- A parallel update U gets committed (i.e. its result becomes the value of the Rx after completion) if and only if the time at which U's computation began (its start time) is greater than the start time of the last-committed parallel update. If another parallel update U' was started in the interim, the result of U is discarded

- The state of the dataflow graph may be temporarily inconsistent as a propagation is happening. This is even more true when multiple propagations are happening simultaneously. However, after all propagations complete and the system stabilizes (quiescience), it is guaranteed that the value of every Rx will be correct, with regard to the most up-to-date values of its dependencies.

- When a single propagation happens, Scala.Rx guarantees that although the dataflow graph may be transiently inconsistent, the Obs which produce side effects will only fire once everything has stabilized.

- In the presence of multiple propagations happening in parallel, Scala.Rx guarantees that each Obs will fire at most once per propagation that occurs. Furthermore, by the time the propagations have completed and the system has stabilized, each Obs will have fired at least once after the Rx it is observing has reached its final value.

This policy is implemented using the java.util.concurrent.AtomicXXX classes. The final compare-start-times-and-replace-if-timestamp-is-greater action is implemented as a STM-style retry-loop on an AtomicReference. This approach is lock free, and since the time required to compute the result is probably far greater than the time spent trying to commit it, the number of retries should in practice be minimal.

Apart from the main update loop, peripheral methods like children, parents, ancestors and descendents are also affected by parallelism. In these cases, if the system is quiescent you're guaranteed to get the correct value. If there are parallel updates and modifications going on, you're guaranteed to get a set of nodes which were part of the list some time during the duration it takes for the method to run, and any node which was part of the list for the entire duration.

###Weak Forward References The weak-forward-references to an Rx from its dependencies is unusual in that unlike the rest of the state regarding the Rx, it is not kept within the Rx itself! Rather, it is kept within its parents. Hence updates to these weak references cannot conveniently be serialized by encapsulating the state within that Rx's state.

###Parallelism and ScalaJS

Since ScalaJS runs on single threaded Javascript VMs, all these guarantees around parallel update semantics is moot since only one Rx will be updating at a time.

As described earlier, the dataflow graph built by Scala.Rx is maintained by a network of WeakReferences. These allow the nodes to send updates to their children while still allowing their children to be garbage collected if necessary. Hence in this example:

val a = Var(0)

for (i <- 0 until 10){

val b = Rx{ a() + 1 }

...

}After b falls out of scope, it is eventually automatically cleaned up by the garbage collector. The exact timing of this is non-deterministic (since it depends on the GC) so in general, you should write code that is not affected by this non-determinism. For example, if the only data structures that b can affect (by triggering Obss, or via side-effects in the body of its Rx) become unreachable together with b (e.g. they're kept on the same object) then it doesn't matter exactly when b stops triggering, since the effect of its triggering will not be visible by that point anyway.

In ScalaJS, WeakReferences are not weak, since Javascript does not have weak references. This means that the Rxs generated in the loop will not get cleaned up, since a must hold a strong reference to them in order to notify them of updates. However, in cases such as this, it may be necessary to manually .kill() the individual Rxs once you're done with them:

val a = Var(0)

for (i <- 0 until 10){

val b = Rx{ a() + 1 }

...

b.kill()

}Alternatively, if you're done with a as well, you can perform a .killAll() on it, which will kill it as well as all of its children and descendents at one go:

val a = Var(0)

for (i <- 0 until 10){

val b = Rx{ a() + 1 }

...

}

a.killAll()On the other hand, often leaking memory is acceptable: often the dataflow graph is relatively static, so even if some memory is kept around unnecessarily, the amount leaked won't grow unbounded. Furthermore, even when you are generating dataflow graphs dynamically (e.g. one for each section of a web page, which may vary) if these dataflow graphs are completely independent, then even if nodes within each graph can't be GCed, each graph can and will be GCed as a whole when all its nodes become unreachable.

It is only when you have a dynamically changing sections of a single dataflow graph where the forward-references prevent GC and nodes need to be killed manually.

This meant that the syntax to write programs in a dependency-tracking way had to be as light weight as possible, that programs written using FRP had to look like their normal, old-fashioned, imperative counterparts. This meant using DynamicVariable instead of implicits to automatically pass arguments, sacrificing proper lexical scoping for nice syntax.

I ruled out using a purely monadic style (like reactive-web), as although it would be far easier to implement the library in that way, it would be a far greater pain to actually use it. I also didn't want to have to manually declare dependencies, as this violates DRY when you are declaring your dependencies twice: once in the header of the Rx, and once more when you use it in the body.

The goal was to be able to write code, sprinkle a few Rx{}s around and have the dependency tracking and change propagation just work. Overall, I believe it has been quite successful at that!

This means many things, but most of all it means having no globals. This greatly simplifies many things for someone using the library, as you no longer need to reason about different parts of your program interacting through the library. Using Scala.Rx in different parts of a large program is completely fine; they are completely independent.

Another design decision in this area was to have the parallelism and propagation-scheduling be left mainly to an implicit ExecutionContext, and have the default to simply run the propagation wave on whatever thread made the update to the dataflow graph.

- The former means that anyone who is used to writing parallel programs in Scala/Akka is already familiar with how to deal with parallelizing Scala.Rx

- The latter makes it far easier to reason about when propagations happen, at least in the default case: it simply happens right away, and by the time that

Var.update()function has returned, the propagation has completed.

Overall, limiting the range of side effects and removing global state makes Scala.Rx easy to reason about, and means a developer can focus on using Scala.Rx to construct dataflow graphs rather than worry about un-predictable far-reaching interactions or performance bottlenecks.

This meant that it had to be easy for a programmer to drop in and out of the FRP world. Many of the papers I read in preparing for Scala.Rx described systems that worked brilliantly on their own, and had some amazing properties, but required that the entire program be written in an obscure variant of an obscure language. No thought at all was given to inter-operability with existing languages or paradigms, which makes it impossible to incrementally introduce FRP into an existing codebase.

With Scala.Rx, I resolved to do things differently. Hence, Scala.Rx:

- Is written in Scala: an uncommon, but probably less-obscure language than Haskell or Scheme

- Is a library: it is plain-old-scala. There is no source-to-source transformation, no special runtime necessary to use Scala.Rx. You download the source code into your Scala project, and start using it

- Allows you to use any programming language construct or library functionality within your Rxs: Scala.Rx will figure out the dependencies without the programmer having to worry about it, without limiting yourself to some inconvenient subset of the language

- Allows you to use Scala.Rx within a larger project without much pain. You can easily embed dataflow graphs within a larger object-oriented universe and interact with them via setting Vars and listening to Obss

Many of the papers reviewed show a beautiful new FRP universe that we could be programming in, if only you ported all your code to FRP-Haskell and limited yourself to the small set of combinators used to create dataflow graphs. On the other hand, by letting you embed FRP snippets anywhere within existing code, using FRP ideas in existing projects without full commitment, and allowing you easy interop between your FRP and non-FRP code, Scala.Rx aims to bring the benefits FRP into the dirty, messy universe which we are programming in today.

Scala.Rx has a number of significant limitations, some of which arise from trade-offs in the design, others from the limitations of the underlying platform.

###No "Empty" Reactives

The API of Rxs in Scala.Rx tries to follow the collections API as far as possible: you can map, filter and reduce over the Rxs, just as you can over collections. However, it is currently impossible to have a Rx which is empty in the way a collection can be empty: filtering out all values in a Rx will still leave at least the initial value (even if it fails the predicate) and Async Rxs need to be given an initial value to start.

This limitation arises from the difficulty in joining together possibly empty Rxs with good user experience. For example, if I have a dataflow graph:

val a = Var()

val b = Var()

var c = Rx{

.... a() ...

... some computation ...

... b() ...

result

}Where a and b are initially empty, I have basically two options:

- Block the current thread which is computing

c, waiting foraand thenbto become available. - Throw an exception when

a()andb()are requested, aborting the computation ofcbut registering it to be restarted whena()orb()become available. - Re-write this in a monadic style using for-comprehensions.

- Use the delimited continuations plugin to transform the above code to monadic code automatically.

The first option is a performance problem: threads are generally extremely heavy weight on most operation systems. You cannot reasonably make more than a few thousand threads, which is a tiny number compared to the amount of objects you can create. Hence, although blocking would be the easiest, it is frowned upon in many systems (e.g. in Akka, which Scala.Rx is built upon) and does not seem like a good solution.

The second option is a performance problem in a different way: with n different dependencies, all of which may start off empty, the computation of c may need to be started and aborted n times even before completing even once. Although this does not block any threads, it does seem extremely expensive.

The third option is a no-go from a user experience perspective: it would require far reaching changes in the code base and coding style in order to benefit from the change propagation, which I'm not willing to require.

The last option is problematic due to the bugginess of the delimited continuations plugin. Although in theory it should be able to solve everything, a large number of small bugs (messing up type inferencing, interfering with implicit resolution) combined with a few fundamental problems meant that even on a small scale project (less than 1000 lines of reactive code) it was getting painful to use.

###No Automatic Parallelization at the Start

As mentioned earlier, Scala.Rx can perform automatic parallelization of updates occurring in the dataflow graph: simply provide an appropriate ExecutionContext, and independent Rxs will have their updates spread out over multiple cores.

However, this only works for updates, and not when the dataflow graph is being initially defined: in that case, every Rx evaluates its body once in order to get its default value, and it all happens serially on the same thread. This limitation arises from the fact that we do not have a good way to work with "empty" Rxs, and we do not know what an Rxs dependencies are before the first time we evaluate it.

Hence, we cannot start all our Rxs evaluating in parallel as some may finish before others they depend on, which would then be empty, their initial value still being computed. We also cannot choose to parallelize those which do not have dependencies on each other, as before execution we do not know what the dependencies are!

Thus, we have no choice but to have the initial definitions of Rxs happen serially. If necessary, a programmer can manually create independent Rxs in parallel using Futures.

###Glitchiness and Redundant Computation

In the context of FRP, a glitch is a temporary inconsistency in the dataflow graph. Due to the fact that updates do not happen instantaneously, but instead take time to computer, the values within an FRP system may be transiently out of sync during the update process. Furthermore, depending on the nature of the FRP system, it is possible to have nodes be updated more than once in a propagation.

This may or may not be a problem, depending on how tolerant the application is of occasional stale inconsistent data. In a single-threaded system, it can be avoided in a number of ways

- Make the dataflow graph static, and perform a topological sort to rank nodes in the order they are to be updated. This means that a node always is updated after its dependencies, meaning they will never see any stale data

- Pause the updating of a node when it tries to call upon a dependency which has not been updated. This could be done by blocking the thread, for example, and only resuming after the dependency has been updated.

However, both of these approaches have problems. The first approach is extremely constrictive: a static dataflow graph means that a large amount of useful behavior, e.g. creating and destroying sections of the graph dynamically at run-time, is prohibited. This goes against Scala.Rx's goal of allowing the programmer to write code "normally" without limits, and letting the FRP system figure it out.

The second case is a problem for languages which do not easily allow computations to be paused. In Java, and by extension Scala, the threads used are operating system (OS) threads which are extremely expensive. Hence, blocking an OS thread is frowned upon. Coroutines and continuations could also be used for this, but Scala lacks both of these facilities.

The last problem is that both these models only make sense in the case of single threaded, sequential code. As mentioned on the section on Concurrency and Parallelism, Scala.Rx allows you to use multiple threads to parallelize the propagation, and allows propagations to be started by multiple threads simultaneously. That means that a strict prohibition of glitches is impossible.

Scala.Rx maintains somewhat looser model: the body of each Rx may be evaluated more than once per propagation, and Scala.Rx only promises to make a "best-effort" attempt to reduce the number of redundant updates. Assuming the body of each Rx is pure, this means that the redundant updates should only affect the time taken and computation required for the propagation to complete, but not affect the value of each node once the propagation has finished.

In addition, Scala.Rx provides the Obss, which are special terminal-nodes guaranteed to update only once per propagation, intended to produce some side effect. This means that although a propagation may cause the values of the Rxs within the dataflow graph to be transiently out of sync, the final side-effects of the propagation will only happen once the entire propagation is complete and the Obss all fire their side effects.

If multiple propagations are happening in parallel, Scala.Rx guarantees that each Obs will fire at most once per propagation, and at least once overall. Furthermore, each Obs will fire at least once after the entire dataflow graph has stabilized and the propagations are complete. This means that if you are relying on Obs to, for example, send updates over the network to a remote client, you can be sure that you don't have any unnecessary chatter being transmitted over the network, and when the system is quiescent the remote client will have the updates representing the most up-to-date version of the dataflow graph.

Scala.Rx was not created in a vacuum, and borrows ideas and inspiration from a range of existing projects.

Scala.React, as described in Deprecating the Observer Pattern, contains a reactive change propagation portion (there called Signals) which is similar to what Scala.Rx does. However, it does much more than that: It contains implementations for using event-streams, and multiple DSLs using delimited continuations in order to make it easy to write asynchronous workflows.

I have used this library, and my experience is that it is extremely difficult to set up and get started. It requires a fair amount of global configuration, with a global engine doing the scheduling and propagation, even running its own thread pools. This made it extremely difficult to reason about interactions between parts of the programs: would completely-separate dataflow graphs be able to affect each other through this global engine? Would the performance of multithreaded code start to slow down as the number of threads rises, as the engine becomes a bottleneck? I never found answers to many of these questions, and had did not manage to contact the author.

The global propagation engine also makes it difficult to get started. It took several days to get a basic dataflow graph (similar to the example at the top of this document) working. That is after a great deal of struggling, reading the relevant papers dozens of times and hacking the source in ways I didn't understand. Needless to say, these were not foundations that I would feel confident building upon.

reactive-web was another inspiration. It is somewhat orthogonal to Scala.Rx, focusing more on event streams and integration with the Lift web framework, while Scala.Rx focuses purely on time-varying values.

Nevertheless, reactive-web comes with its own time-varying values (called Signals), which are manipulated using combinators similar to those in Scala.Rx (map, filter, flatMap, etc.). However, reactive-web does not provide an easy way to compose these Signals: the programmer has to rely entirely on map and flatMap, possibly using Scala's for-comprehensions.

I did not like the fact that you had to program in a monadic style (i.e. living in .map() and .flatMap() and for{} comprehensions all the time) in order to take advantage of the change propagation. This is particularly cumbersome in the case of [nested Rxs](Basic-Usage#nesting), where Scala.Rx's

// a b and c are Rxs

x = Rx{ a() + b().c() }becomes

x = for {

va <- a

vb <- b

vc <- vb.c

} yield (va + vc)As you can see, using for-comprehensions as in reactive-web results in the code being significantly longer and much more obfuscated.

Knockout.js does something similar for Javascript, along with some other extra goodies like DOM-binding. In fact, the design and implementation and developer experience of the automatic-dependency-tracking is virtually identical. This:

this.firstName = ko.observable('Bob');

this.lastName = ko.observable('Smith');

fullName = ko.computed(function() {

return this.firstName() + " " + this.lastName();

}, this);is semantically equivalent to the following Scala.Rx code:

val firstName = Var("Bob")

val lastName = Var("Smith")

fullName = Rx{ firstName() + " " + lastName() }a ko.observable maps directly onto a Var, and a kocomputed maps directly onto an Rx. Apart from the longer variable names and the added verbosity of Javascript, the semantics are almost identical.

Apart from providing an equivalent of Var and Rx, Knockout.js focuses its efforts in a different direction. It lacks the majority of the useful combinators that Scala.Rx provides, but provides a great deal of other functionality, for example integration with the browser's DOM, that Scala.Rx lacks.

This idea of change propagation, with time-varying values which notify any value which depends on them when something changes, part of the field of Functional Reactive Programming. This is a well studied field with a lot of research already done. Scala.Rx builds upon this research, and incorporates ideas from the following projects:

All of these projects are filled with good ideas. However, generally they are generally very much research projects: in exchange for the benefits of FRP, they require you to write your entire program in an obscure variant of an obscure language, with little hope inter-operating with existing, non-FRP code.

Writing production software in an unfamiliar paradigm such as FRP is already a significant risk. On top of that, writing production software in an unfamiliar language is an additional variable, and writing production software in an unfamiliar paradigm in an unfamiliar language with no inter-operability with existing code is downright reckless. Hence it is not surprising that these libraries have not seen significant usage. Scala.Rx aims to solve these problems by providing the benefits of FRP in a familiar language, with seamless interop between FRP and more traditional imperative or object-oriented code.

Copyright (c) 2013, Li Haoyi (haoyi.sg at gmail.com)

Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this software and associated documentation files (the "Software"), to deal in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions:

The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Software.

THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.