Hexi is a fun and easy way to make HTML5 games or any other kind interactive media using pure JavaScript code. Take a look at the feature list and the examples folder to get started. Keep scrolling, and you'll find a complete Quick Start Guide and beginner's tutorials ahead. If you've never made a game before, the tutorials are the best place to start.

What's great about Hexi? You get all the power of WebGL rendering with a streamlined API that lets you write your code in a minimalist, declarative way. It makes coding a game as easy and fun as writing poetry or drawing. Try it! If you need any help or have any questions, post something in this repository's Issues. The Issues page is is Hexi's friendly chat room - don't be afraid to ask for help :)

You only need one file from this repository to get started using Hexi:

hexi.min.js. That's all! Link it to your HTML document with a <script> tag, and go for it!

Hexi has been written, from the ground up, in the latest version of

JavaScript (ES6/7, 20015/6) but is compiled down to ES5 (using Babel) so that it will run anywhere. What do you need to know before you start using Hexi? You should have a reasonable understanding of HTML and JavaScript. You don't have to be an expert, just an ambitious beginner with an eagerness to learn. If you don't know HTML and JavaScript, the best place to start learning it is this book:

Foundation Game Design with HTML5 and JavaScript

I know for a fact that it's the best book, because I wrote it!

Ok, got it? Do you know what JavaScript variables, functions, arrays and objects are and how to use them? Do you know what JSON data files are? Have you used the Canvas Drawing API? Then you're ready to start using Hexi!

Of course, Hexi is completely free to use: for-anything, for-ever! It was written in Canada (Toronto, Hamilton), India (Kullu Valley, Ladakh), Nepal (Kathmandu, Pokhara, Annapurna Base Camp), Thailand (Ko Phangan, Ko Tao) and South Africa (Cape Town), and is the result of 15 years' research into API usability for game design. The name, "Hexi" comes from "Hex" + "Pixi" = "Hexi". It has absolutely no other meaning.

- Hexi's Features

- Modules

- Quick start

- The HTML container page

- Hexi's architecture

- Setting up and starting Hexi

- The load function

- The setup function

- The play function

- Taking it further

- Tutorials

- Treasure Hunter

1. Setting up the HTML container page

2. Initializing the Ga engine

3. Define your "global" variables

4. Initialize your game with a setup function

- Customizing the canvas

- Creating the

chimessound object - Creating game scenes

- Making sprites

- Positioning sprites

- Assigning dynamic properties

- Creating the enemy sprites

- The health bar

- The game over scene

- Keyboard interactivity

- Setting the game state 5. Game logic with the play function loop

- Moving the player sprite

- Containing sprites inside the screen boundaries

- Collision with the enemies

- Collision with the treasure

- Ending the game 6. Using images

- Individual images

- Loading image files

- Making sprites with images

- Fine-tuning the containment area 7. Using a texture atlas

- Preparing the images

- loading the texture atlas

- Alien Armada 1. Load and use a custom font 2. Scale and center the game in the browser 3. A loading progress bar 4. Shooting bullets 5. Sprite states 6. Generating random aliens

- Flappy Fairy! 1. Make a button 2. Making the fairy fly 3. Make a scrolling background 4. The fairy dust explosions 5. Use a particle emitter 6. Creating and moving the pillars

- Integration with HTML and CSS

- A Guide to the examples

Here's Hexi's core feature list:

- All the most important sprites you need: rectangles, circles, lines, text, image sprites and animated "MovieClip" style sprites. You can make any of these sprites with one only line of code. You can also create your own custom sprite types.

- A complete scene graph with nested child-parent hierarchies (including

a

stage, andaddChild/removeChildmethods), local and global coordinates, depth layers, and rotation pivots. groupsprites together to make game scenes.- A game loop with a user-definable

fpsand fully customizable and drop-dead-simple game state manager.pauseandresumethe game loop at any time. - Tileset (spritesheet) support using

frameandfilmstripmethods to make sprites using tileset frames. - Built-in texture atlas support for the popular Texture Packer format.

- A keyframe animation and state manager for sprites. Use

showto display a sprite's image state. UseplayAnimationto play a sequence of frames (in aloopif you want to). Useshowto display a specific frame number. Usefpsto set the frame rate for sprite animations which is independent from the game's frame rate. - Interactive

buttonsprites withup,overanddownstates. - Any sprite can be set to

interactto receive mouse and touch actions. Intuitivepress,release,over,outandtapmethods for buttons and interactive sprites. - Easy-to-use keyboard key bindings. Easily define your own with the

keyboardmethod. - A built-in universal

pointerthat works with both the mouse and touch. Assign your own custompress,releaseandtapmethods or use any of the pointer's built-in properties:isUp,isDown,tapped,xandy. Define as many pointers as you need for multi-touch. (It also works with isometric maps!) - Conveniently position sprites relative to other sprites using

putTop,putRight,putBottom,putLeftandputCenter. Align sprites horizontally or vertically usingflowRight,flowLeft,flowUporflowDown. - A universal asset loader to pre-load images, fonts, sounds and JSON data files. All popular file formats are supported. You can load new assets into the game at any time.

- An optional

loadstate that lets you run actions while assets are loading. You can use theloadstate to add a loading progress bar. - A fast and focused Pixi-based rendering engine. If Pixi can do it, so can Hexi! Hexi

is just a thin layer of code that sits on top of Pixi. And you can access the

global

PIXIobject at any time to write pure Pixi code directly if you want to. Hexi includes the latest stable version of Pixi v3.0 automatically bundled for you. - A sophisticated game loop using a fixed timestep with variable rendering and sprite interpolation. That means you get butter-smooth sprite animations at any framerate.

- A compact and powerful "Haiku" style API that's centered on shallow, composable components. Get more done writing less code.

- Import and play sounds using a built-in WebAudio API sound manager.

Control sounds with

play,pause,stop,restart,playFrom,fadeInandfadeOutmethods. Change a sound'svolumeandpan. - Generate your own custom sound effects from pure code with

the versatile

soundEffectmethod. - Shake sprites or the screen with

shake. - Tween functions for sprite and scene transitions:

slide,fadeIn,fadeOut,pulse,breathe,wobble,strobeand some useful low-level tweening methods to help you create your own custom tweens. - Make a sprite follow a connected series of waypoints with

walkPathandwalkCurve. - A handful of useful convenience functions:

followEase,followConstant,angle,distance,rotateAroundSprite,rotateAroundPoint,wait,randomInt,randomFloat,containandoutsideBounds. - A fast, universal

hitmethod that handles collision testing and reactions (blocking and bounce) for all types of sprites. Use one collision method for everything: rectangles, circles, points, and arrays of sprites. Easy! - A companion suite of lightweight, low-level 2D geometric collision methods.

- A loading progress bar for game assets.

- Make sprites shoot things with

shoot. - Easily plot sprites in a grid formation with

grid. - Use a

tilingSpriteto easily create a seamless scrolling background. - A

createParticlesfunction for creating all kinds of particle effects for games. Use theparticleEmitterfunction to create a constant stream of particles. - Use

scaleToWindowto make the game automatically scale to its maximum size and align itself for the best fit inside the browser window. - Tiled Editor support using

makeTiledWorld. Design your game in Tiled Editor and access all the sprites, layers and objects directly in your game code. It's an extremely fun, quick and easy way to make games. - A versatile,

hitTestTilemethod that handles all the collision checking you'll need for tile-based games. You can use it in combination with the any of the 2D geometric collision methods for optimized broadphase/narrowphase collision checking if you want to. - Use

updateMapto keep a tile-based world's map data array up-to-date with moving sprites. - Create a

worldCamerathat follows sprites around a scrolling game world. - A

lineOfSightfunction that tells you whether a sprite is visible to another sprite. - Seamless integration with HTML and CSS elements for creating rich user interfaces. Use Hexi also works with Angular, React and Elm!

- A complete suite of tools for easily creating isometric game worlds, including: an isometric mouse/touch pointer, isometric tile collision using

hitTestIsoTile, and full Tiled Editor isometric map support usingmakeIsoTiledWorld. - A

shortestPathfunction for doing A-Star pathfinding through tile based environments like mazes and atileBasedLineOfSightfunction to tell you whether sprites in a maze game environment can see each other. - Yes, Hexi applications meet W3C accessibilty guidelines thanks to the

accessibleproperty provided by the Pixi renderer (yay Pixi!)

Hexi contains a collection of useful modules, and you use any of the properties or methods of these modules in your high-level Hexi code.

- Pixi: The world's fastest 2D WebGL and canvas renderer.

- Bump: A complete suite of 2D collision functions for games.

- Tink: Drag-and-drop, buttons, a universal pointer and other helpful interactivity tools.

- Charm: Easy-to-use tweening animation effects for Pixi sprites.

- Dust: Particle effects for creating things like explosions, fire and magic.

- Sprite Utilities: Easier and more intuitive ways to create and use Pixi sprites, as well adding a state machine and animation player

- Game Utilities: A collection of useful methods for games.

- Tile Utilities: A collection of useful methods for making tile-based game worlds with Tiled Editor. Includes a full suite of isometric map utilities.

- Sound.js: A micro-library for loading, controlling and generating sound and music effects. Everything you need to add sound to games.

- Smoothie: Ultra-smooth sprite animation using true delta-time interpolation. It also lets you specify the fps (frames-per-second) at which your game or application runs, and completely separates your sprite rendering loop from your application logic loop.

Read the documents at the code repositories for each of these modules to find out what you can do with them and exactly how they work. Because they're all built into Hexi, you don't have to install them yourself - they just work right out-of-the-box.

Hexi lets you access most of these module methods and properties as

top-level objects. For example, if you want to access the hit method

from the Bump collision module, you can do it like this:

g.hit(spriteOne, spriteTwo);But you can also access the Bump module directly if you need to, like this:

g.bump.hit(spriteOne, spriteTwo);(This assumes that your Hexi instance is called g);

Just refer to the module name using lowerCamelCase. That means you can

access the Smoothie module as smoothie and the Sprite Utilities

module as spriteUtilities.

There are two exceptions to this convention. You can access the Pixi

global object directly as PIXI. Also, the functions in the Sound.js module

are also only accessible as top-level global objects. This is was done

to simplify the way these modules are integrated with Hexi, and

maintain the widest possible cross-platform compatibility.

If you're a developer and would like to contribute to Hexi, the best way is to contribute new and improved features to these modules. Or, if you're really ambitious, propose a new module to the Hexi development team (in this repo's Issues, and maybe we'll add it to Hexi's core!)

To start working with Hexi quickly, take a look at the Quick Start

project in Hexi's examples

folder.

You'll find the HTML container page here and the JavaScript

source file here. The source code is fully commented and explains how all everything works so, if you want to, you can just skip straight to that file and read through it. (You'll find the complied, ES5, version of the JavaScript file in the bin folder.)

The Quick Start project is a tour of all of Hexi's main features, and you can use it as a template for making your own new Hexi applications. Click on the image below to try a working example:

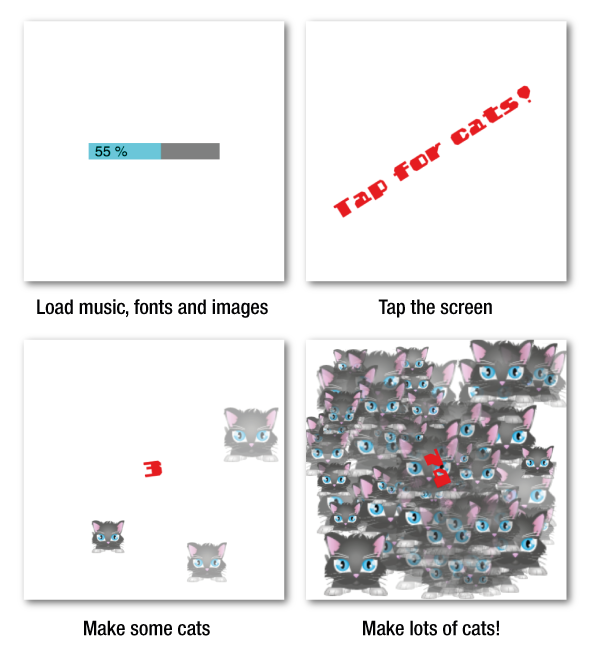

You'll first see a loading bar that shows you the percentage of files (sounds and images) being loaded. You'll then see a spinning message that asks to you to tap on the screen to create cats. Cats will appear on the screen wherever you click with the pointer while music plays in the background. (Oops, Sorry! I forgot to warn you about the music!) A text field rotates and counts the number of cats you've created. The cats themselves move and bounce around the screen, while scaling in size and oscillating their transparency. Here's an illustration of what you'll see:

Why cats? Because.

If you know how this Quick Start application was made, you'll be well on your way to being productive with Hexi fast - so let's find out!

(Note: If you're new to game programming and feel you need a gentler, more methodical, introduction to Hexi, check out the Tutorials section ahead. You'll learn how to make 3 complete games from scratch, and each game gradually builds on the skills you learnt in the previous game.)

The only file you need to start using Hexi is

hexi.min.js. It has an incredibly simple "installation": Just link it to an HTML page with a <script> tag. Then link your main JavaScript file that will contain your game or application code. Here's what a typical Hexi HTML container page might look like:

<!doctype html>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Hexi</title>

<body>

<script src="hexi.min.js"></script>

<script src="main.js"></script>

</body>You can, of course, load as many external script files that you need for your game.

If you need a little more fine-control, you can alternatively load

Hexi using three separate files: The Pixi renderer, Hexi's modules, and Hexi's core.jsfile.

<!doctype html>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Hexi</title>

<body>

<!-- Pixi renderer, Hexi's modules, and Hexi's core -->

<script src="pixi.js"></script>

<script src="modules.js"></script>

<script src="core.js"></script>

<!-- Main application file -->

<script src="bin/quickStart.js"></script>

</body>An advantage to doing this is that it lets you swap out Hexi's internal version of Pixi, with your own custom build of Pixi, or a specific version of Pixi that you want to use. Or maybe you made some other crazy modifications to Hexi's modules that you want to try out. But typically, you'll probably never need to do this.

All the fun happens in your main JavaScript file. Hexi applications have a very simple but flexible architecture that you can scale to any size you need. Small games with a few hundred lines of code or big games with a few hundred files - Hexi can do it! Here's the structure of at typical Hexi application:

- Start Hexi.

- The

loadfunction, that will run while your files are loading. - The

setupfunction, which initializes your game objects, variables and sprites. - The

playfunction, which is your game or application logic that runs in a loop.

And Here's what this actually looks like in real code:

//1. Setting up and starting Hexi

//An array of files you want to load

let thingsToLoad = ["anyFiles", "youWant", "toLoad"];

//Initialize and start Hexi

let g = hexi(canvasWidth, canvasHeight, setup, thingsToLoad, load);

g.start();

//2. The `load` function that will run while your files are loading

function load(){

//Display an optional loading bar

g.loadingBar();

}

//3. The `setup` function, which initializes your game objects, variables and sprites

function setup() {

//Create your game objects here

//Set the game state to `play` to start the game loop

g.state = play;

}

//4. The `play` function, which is your game or application logic that runs in a loop

function play(){

//This is your game loop, where you can move sprites and add your

//game logic

}This simple model is all you need to create any kind of game or application. You can use it as the starting template for your own projects, and this same basic model can scale to any size.

Let's find out how this architectural model was used to build the Quick Start application.

First, create an array that lists all the files you want to load. The Quick Start project loads an image file, a font file, and a music file.

let thingsToLoad = [

"images/cat.png",

"fonts/puzzler.otf",

"sounds/music.wav"

];If you don't have any files you want to load, just skip this step.

Next, initialize Hexi with the hexi function. Here's how to initialize a

new Hexi application with a screen size of 512x512 pixels. It tells

Hexi to load the files in the thingsToLoad array, run a function called load while

its loading, and then run a function called setup when everything is ready to go.

let g = hexi(512, 512, setup, thingsToLoad, load);You can now access the instance of Hexi in your application through an

object called g (Although, you can give this any name you like. I

like using "g" because it stands for "game", and is short to type.)

The hexi function has 5 arguments, although only the first 3 are required.

- Canvas width.

- Canvas height.

- The

setupfunction. - The

thingsToLoadarray you defined above. This is optional. - The

loadfunction. This is also optional.

If you skip the last two arguments, Hexi will skip the loading process and jump straight to the setup function.

Optionally Set the frames per second at which the game logic loop should run.

(Sprites will be rendered independently, with interpolation, at full 60 fps)

If you don't set the fps, Hexi will default to an fps of 60.

g.fps = 30;Setting an fps lower than 60 gives you much more performance overhead to play with, and your games will still look great.

You can also optionally add a border and set the background color.

g.border = "2px red dashed";

g.backgroundColor = 0x000000;And, if you want to scale and align the game screen to the maximum browser

window size, you can use the scaleToWindow method.

g.scaleToWindow();Finally, call the start method to get Hexi running

g.start();This is important! Without calling the start method Hexi won't

start!

If you supplied Hexi with a function called load when you initialized it, you can display a loading bar and loading progress information. Just create a function called load, like this:

function load(){

//Display the file currently being loaded

console.log(`loading: ${g.loadingFile}`);

//Display the percentage of files currently loaded

console.log(`progress: ${g.loadingProgress}`);

//Add an optional loading bar

g.loadingBar();

}Now that you've started Hexi and loaded all your files, you can start

making things! This happens in the setup function. If you have any

objects or variables that you want to use across more than one

function, define them outside the setup function, like this:

//These things will be used in more than one function

let cats, message;

//Use the `setup` function to create things

function setup(){

//... create things here! ...

}Let's find out how the code inside the setup function works. We're going

to be making cats - lots of cats! - so it's useful to create a group called

catsto keep them all together.

cats = g.group();In the Quick Start project you can make a new cat by tapping the

screen with the mouse (or touch.) So, we need a function that will

produce new cat sprites for us. (Sprites are interactive graphics that you can animate and move around the screen.) Hexi lets you create a new sprite using the sprite method. Just supply sprite with file name that you want to use for the sprite. Each new cat sprite that's created should be positioned and added add to the cats group, using the addChild method. We also want the cat to animate its scale using the breathe method and animate its transparency using the pulse method. A function called makeCats does all this. makeCats takes two arguments: the x and y

position where you want the cat to appear, relative to the top left corner of the screen.

let makeCat = (x, y) => {

//Create the cat sprite. Supply the `sprite` method with

//the name of the loaded image that should be displayed

let cat = g.sprite("images/cat.png");

//Set the cat's position

cat.setPosition(x, y);

//You can alternatively set the position my modifying the sprite's `x` and

//`y` properties directly, like this

//cat.x = x;

//cat.y = y;

//Add some optional tween animation effects from the Hexi's

//built-in tween library (called Charm). `breathe` makes the

//sprite scale in and out. `pulse` oscillates its transparency

g.breathe(cat, 2, 2, 20);

g.pulse(cat, 10, 0.5);

//Set the cat's velocity to a random number between -10 and 10

cat.vx = g.randomInt(-10, 10);

cat.vy = g.randomInt(-10, 10);

//Add the cat to the `cats` group

cats.addChild(cat);

};(You can find out more about how the breathe and pulse methods work to

animate the cat in the tweening example in the examples folder.)

We also need to create a text sprite to display the words "Tap for

cats!" We can use Hexi's text method to do that.

message = g.text("Tap for cats!", "38px puzzler", "red");The text method's arguments are the text you want to display, the

font size and family, and the color (You can use any HTML/CSS color

string value, RGBA or HSLA values).

Use Hexi's putCenter method to center the text inside the stage.

g.stage.putCenter(message);What's the stage? It's the root container that all Hexi sprites

belong to when they're first created.

You can also use putLeft, putRight, putTop or putBottom methods to help you align objects relative to other objects. The optional 2nd and 3rd arguments of these methods define the x and y offset, which help you fine-tune positioning.

Because we want the text message to rotate around its center point we

have to set its pivotX and pivotY values to 0.5.

message.pivotX = 0.5;

message.pivotY = 0.5;0.5 means "the very center of the sprite".

You can also use this alternative syntax to set the pivot point:

message.setPivot(0.5, 0.5);We need some way to tell Hexi to create a new cat whenever the screen

is clicked or tapped. We also want the text message to tell us how many cats are currently on the screen. Hexi has a built in pointer object with a tap method that we can program to help us do this.

g.pointer.tap = () => {

//Supply `makeCat` with the pointer's `x` and `y` coordinates.

makeCat(g.pointer.x, g.pointer.y);

//Make the `message.content` display the number of cats

message.content = `${cats.children.length}`;

};We also want the music file that we loaded to start playing. We can

access the music sound object with Hexi's sound method. Use the sound object's loop

method to make it loop continuously, and use play to start it playing right away.

let music = g.sound("sounds/music.wav");

music.loop = true;

music.play();We're now done setting everything up! That means we're finished with

our application's setup state and can now switch the state to play. Here's how to do that:

g.state = play;The play state is a function that will run in a loop, and is where

all our application logic is. Let's find out how that works next.

The last thing you need in your Hexi application is a play function.

function play() {

//All this code will run in a loop

}The play function is called in a continuous loop, at whatever fps

(frames per second) value you set. This is your game logic loop. (The

render loop will be run by Hexi in the background at the maximum fps

your system can handle.) You can pause Hexi's game loop at any time

with the pause method, and restart it with the resume method.

(Check out the Flappy Fairy project to find out how pause and

resume can be used to manage an application with complex states.)

The Quick Start project's play function just does two things: It

makes the text rotate, and moves and bounces the cats around the

screen. Here's the entire play function that does all this.

function play() {

//Rotate the text

message.rotation += 0.1;

//Loop through all of the cats to make them move and bounce off the

//edges of the stage

cats.children.forEach(cat => {

//Make the cat bounce off the screen edges

let collision = g.contain(cat, g.stage, true);

//Move the cat

g.move(cat);

});

}That's all! Compared to all the work we put into the setup function, the

play function does practically nothing! But how does it work?

It first makes the text rotate around its center by updating the

message text sprite's rotation property by 0.1 radians.

message.rotation += 0.1;Because this new rotation value is being applied to the old rotation value inside a continuous loop, it gradually increases the value and makes the text rotate.

The next thing the code does is loop through all the sprites in the

cat group's children array.

cats.children.forEach(cat => {

//Loop through each `cat` sprite in the `chidren` array

});All Hexi groups have an array called children which

tells you which sprites they contain. Whenever you add a sprite to a

group using the addChild method, the sprite is added to the group's

children array. Hexi's root container, called the stage, also has

a children array that contains all the sprites and groups in your

Hexi application. Even sprite objects have a children array, and

that means you can use addChild to group sprites with other sprites

to create complex game objects.

When the code loops through each cat, it first checks whether the cat

is touching the edges of the screen and, if it is, it bounces it away

in the opposite direction. Hexi's contain method helps us do this.

let collision = g.contain(cat, g.stage, true);Setting the third argument to true is what causes the cat to bounce.

The cat moves around the screen with the help of the move method.

g.move(cat);The move method updates the sprite's position by its vx and vy velocity values. (All Hexi sprites have vx and vy values, which are initialized to zero). You can move more than one sprite at a time by supplying move with a list of sprites, separated by commas. You can even supply it with an array that that contains all the sprites you want to move. Here's what move is actually doing under the hood:

cat.x += cat.vx;

cat.y += cat.vy;And that's all there is to it! This is everything you know about the Quick Start application, and almost everything you need to know about Hexi!

With this basic Hexi architecture, you can create anything. Just set Hexi's state property to any other function to switch the behaviour of your application. Here's how:

g.state = anyStateFunction;States are just plain old JavaScript funtctions! Nice and simple!

Write as many state functions as you need. If it's a small project, you can keep all these functions in one file. But, for a big project, load your functions from external JS files as you need them. Use any module system you prefer, like ES6 modules, CommonJS, AMD, or good old HTML <script> tags. This simple architectural model can scale to any size, and is the only architectural model you need to know. Keep it simple and stay happy!

Now that you've got a broad overview of how Hexi works, read through the tutorials to dive into the details.

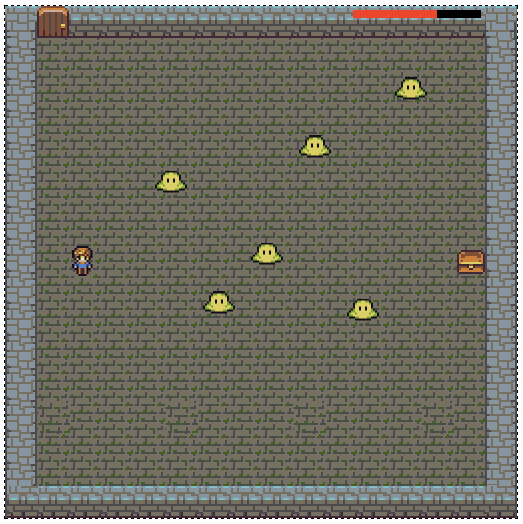

The first game we're going to make is a simple object collection and

enemy avoidance game called Treasure Hunter. Open the file

01_treasureHunter.html in a web browser. (You'll find it in Hexi's

tutorials folder, and you'll need to run it in a

webserver). If you don't

want to bother setting up a webserver, use a text-editor like

Brackets that will launch one for you

automatically (see Brackets' documentation for this feature).

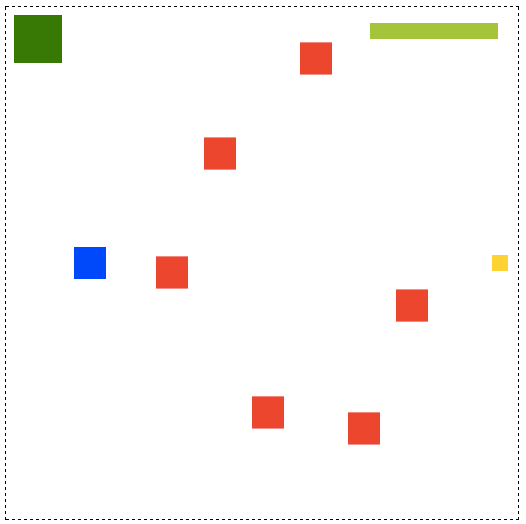

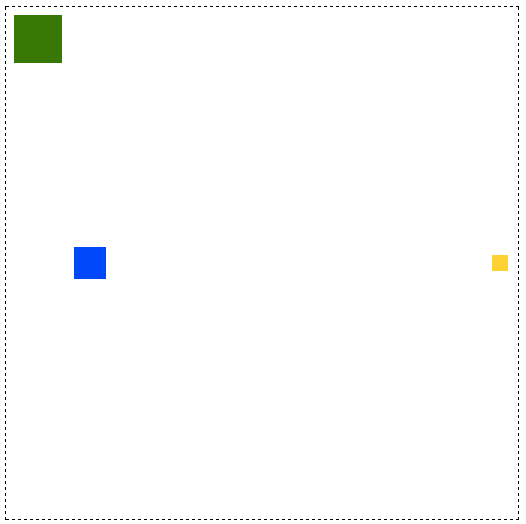

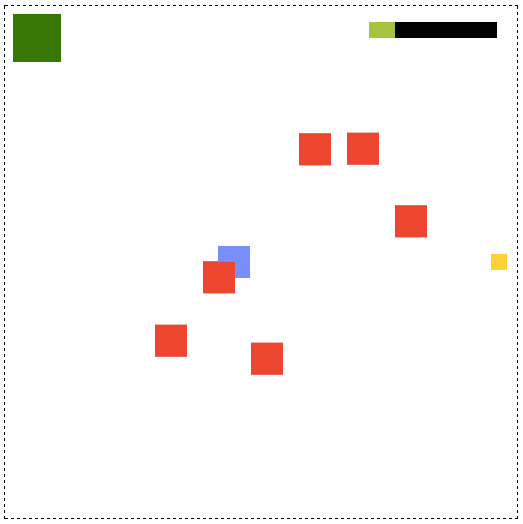

(Follow the link in the image above to play the game.) Use the keyboard to move the explorer (the blue square), collect the treasure (the yellow square), avoid the monsters (the red squares) and reach the exit (the green square.) Yes, you have to use your imagination - for now.

Here's the complete JavaScript source code:

Don't be fooled by it's apparent simplicity. Treasure Hunter contains everything a video game needs:

- Interactivity

- Collision

- Sprites

- A game loop

- Scenes

- game logic

- "Juice" (in the form of sounds)

(What's juice? Watch this video and read this article to learn about this essential game design ingredient.)

If you can make a simple game like Treasure Hunter, you can make almost any other kind of game. Yes, really! Getting from Treasure Hunter to Skyrim or Zelda is just a matter of lots of small steps; adding more detail as you go. How much detail you want to add is up to you.

In the first stage of this tutorial you'll learn how the basic Treasure Hunter game was made, and then we'll add some fun features like images and character animation that will give you a complete overview of how the Hexi works.

If you're an experienced game programmer and

quick self-starter, you might find the code in Hexi's examples folder to

be a more productive place to start learning - check it out. The fully

commented

code in the examples folder also details specific, and advanced uses

of features, that aren't

covered in these tutorials. When you're finished working through these

tutorials, the examples will take you on the next stage of your

journey.

Before you can start programming in JavaScript, you need to set up a

minimal HTML container page. The HTML page loads hexi.min.js which

is the only file you need to use all of Hexi's

features. It also load the treasureHunter.js file, which is the

JavaScript file that contains all the game code.

<!doctype html>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Treasure hunter</title>

<body>

<!-- Hexi -->

<script src="../bin/hexi.min.js"></script>

<!-- Main application file -->

<script src="bin/treasureHunter.js"></script>

</body>This is the minimum amount of HTML code you need for a valid HTML5 document.

The file paths may be different on your system, depending on how you've set up your project file structure.

The next step is to write some JavaScript code that initializes and starts Hexi

according to some parameters that you specify. This bit of

code below initializes a game with a screen size of 512 by 512 pixels.

It also pre-loads the chimes.wav sound file from the sounds

folder.

//Initialize Hexi and load the chimes sound file

let g = hexi(512, 512, setup, ["sounds/chimes.wav"]);

//Scale the game canvas to the maximum size in the browser

g.scaleToWindow();

//Start the Hexi engine.

g.start();You can see that the result of the hexi function is being assigned to

an variable called g.

let g = hexi(//...Now, whenever you want to use any of Hexi's custom

methods or objects in your game, just prefix it with g. (You don't

have to use g to represent the game engine, you can use any variable

name you want. g is just nice, short, and easy to remember; g =

"game".)

In this example Hexi creates a canvas element with a size of 512 by 512 pixels. That's specified by the first two arguments:

512, 512, setup,The third argument, setup, means that as soon as Hexi is initialized,

it should look for and run a function in your game code called setup.

Whatever code is in the setup function is entirely up to you, and

you'll soon see how you can used it to initialize a game. (You don't

have to call this function setup, you can use any name you like.)

Hexi lets you pre-load game assets with an optional 4th argument, which

is an array of file names. In this first example, you only need to preload one file: chimes.wav

You can see that the full file path to chimes.wav is listed as a

string in the

initialization array:

["sounds/chimes.wav"]You can list as many game assets as you like here, including images, fonts, and JSON files. Hexi will load all these assets for you before running any of the game code.

Hexi just implement's Pixi's superb resource loader

under-the-hood. You can access the loader directly through Hexi's loader

property, and you can access the resources through the resources property. Or, just use PIXI.loader directly, if you want to. You can

find out more about how Pixi's loader works here.

We want the game canvas to scale to

the maximum size of the browser window, so that it displays as large

as possible. We can use a useful method called scaleToWindow to do

this for us.

g.scaleToWindow();scaleToWindow will center your game for the best fit. Long, wide

game screens are centered vertically. Tall or square screens are

centered horizontally. If you want to specify your own browser

background color that borders the game, supply it in scaleToWindow's

arguments, like this:

g.scaleToWindow("seaGreen");

The last thing you need to do is call Hexi's start method.

g.start();This is the switch that turns the Hexi engine on.

After Hexi has been started, declare all the variables that your game functions will need to use.

let dungeon, player, treasure, enemies, chimes, exit,

healthBar, message, gameScene, gameOverScene;Because they're not enclosed inside a function, these variables are "global" in the sense that you can use them across all of your game functions. (They're not necessarily "global" in the sense that they inhabit the global JavaScript name-space. If you want to ensure that they aren't, wrap all of your JavaScript code in an enclosing immediate function to isolate it from the global space. Or, if you want to do it the fancy way, use JavaScript ES6/2015 modules or classes, to enforce local scope.

As soon as Hexi starts, it will look for and run a function in your game

code called setup (or whatever other name you want to give this

function.) The setup function is only run once, and lets you perform

one-time setup tasks for your game. It's a great place to create and initialize

objects, create sprites, game scenes, populate data arrays or parse

loaded JSON game data.

Here's an abridged, birds-eye view of the setup function in Treasure Hunter,

and the tasks that it performs.

function setup() {

//Create the `chimes` sound object

//Create the `gameScene` group

//Create the `exit` door sprite

//Create the `player` sprite

//Create the `treasure` sprite

//Make the enemies

//Create the health bar

//Add some text for the game over message

//Create a `gameOverScene` group

//Assign the player's keyboard controllers

//set the game state to `play`

g.state = play;

}The last line of code, g.state = play is perhaps the most important

because it starts the play function. The play function runs all the game logic

in a loop. But before we look at how that works, let's see what the

specific code inside the setup function does.

You'll remember from the code above that we preloaded a sound file

into the game called chimes.wav. Before you can use it in your game,

you have to make a reference to it using Hexi's sound method,

like this:

chimes = g.sound("sounds/chimes.wav");Hexi has a useful method called group that lets you group game objects

together so that you can work with them as one unit. Groups are used for

grouping together special objects called sprites (which you'll

learn all about in the next section.) But they're also used for making game scenes.

Treasure Hunter uses two game scenes: gameScene which is the main game,

and gameOverScene which is displayed when the game is finished.

Here's how the gameScene is made using the group method:

gameScene = g.group();After you've made the group, you can add sprites (game objects) to the gameScene, using

the addChild method.

gameScene.addChild(anySprite);Or, you can add multiple sprites at one time with the add method, like this:

gameScene.add(spriteOne, spriteTwo, spriteThree);Or, if you prefer, you can create the game scene after you've made all the sprites, and group all the sprites together with one line of code, like this:

gameScene = g.group(spriteOne, spriteTwp, spriteThree);You'll see a few different examples of how to add sprites to groups in the examples ahead.

But what are sprites, and how do you make them?

Sprites are the most important elements in any game. Sprites are

just graphics (shapes or images) that you can control with

special properties. Everything you can see in your games, like

game characters, objects and backgrounds, are sprites. Hexi lets you make

5 kinds of basic sprites: rectangle, circle, line, text, and

sprite (an image-based sprite). You can make almost any 2D action game

with these basic sprite types. (If they aren't enough, you can also define your own custom

sprite types.) This first version of Treasure Hunter

only uses rectangle sprites. You can make a rectangle sprite like

this:

let box = g.rectangle(

widthInPixels,

heightInPixels,

"fillColor",

"strokeColor",

lineWidth,

xPosition,

yPosition

);You can use Hexi's circle method to make a circular shaped sprite:

let ball = g.circle(

diameterInPixels,

"fillColor",

"strokeColor",

lineWidth,

xPosition,

yPosition

);It's often useful to prototype a new game using only rectangle and

circle sprites, because that can help you focus on the mechanics of your

game in a pure, elemental way. That's what this first version of

Treasure Hunter does. Here's the code from the setup function that

creates the exit, player and treasure sprites.

//The exit door

exit = g.rectangle(48, 48, "green");

exit.x = 8;

exit.y = 8;

gameScene.addChild(exit);

//The player sprite

player = g.rectangle(32, 32, "blue");

player.x = 68;

player.y = g.canvas.height / 2 - player.halfHeight;

gameScene.addChild(player);

//Create the treasure

treasure = g.rectangle(16, 16, "gold");

//Position it next to the left edge of the canvas

treasure.x = g.canvas.width - treasure.width - 10;

treasure.y = g.canvas.height / 2 - treasure.halfHeight;

//Alternatively, you could use Ga's built in convience method

//called `putCenter` to postion the sprite like this:

//g.stage.putCenter(treasure, 208, 0);

//Create a `pickedUp` property on the treasure to help us Figure

//out whether or not the treasure has been picked up by the player

treasure.pickedUp = false;

//Add the treasure to the `gameScene`

gameScene.addChild(treasure);Notice that after each sprite is created, it's added to the

gameScene using addChild. Here's what the above code produces:

Let's find out a little more about how these sprites are positioned on the canvas.

All sprites have x and y properties that you can use to precisely

position sprites on the canvas. The x and y values refer to the sprites' pixel

coordinates relative to the canvas's top left corner. The top

left corner has x and y values of 0. That means any

positive x and y values you assign to sprites will position them left (x) and down

(y) relative to that corner point. For example, Here's the

code that positions the exit door (the green square).

exit.x = 8;

exit.y = 8;You can see that this code places the door 8 pixel to the right and 8 pixels below the

canvas's top left corner. Positive x values position sprites to the

right of the canvas's left edge. Positive y values position them

below the canvas's top edge.

Sprites also have width and height

properties that tell you their width and height in pixels. If you need

to find out what half the width or half the height of a sprite is, use

halfWidth and halfHeight.

Hexi also has a some convenience methods that help you quickly position

sprites relative to other sprites: putTop, putRight, putBottom, putLeft and putCenter.

For example, here are the lines from the code above that

position the treasure sprite (the gold box). The code places the

treasure 26 pixels to the left of the

canvas's right edge, and centers it vertically.

treasure.x = g.canvas.width - treasure.width - 10;

treasure.y = g.canvas.height / 2 - treasure.halfHeight;That's a lot of complicated positioning code to write. Instead, you

could use Hexi's built-in putCenter method to achieve the same effect

like this:

g.stage.putCenter(treasure, 220, 0);What is the stage? It's the root container for all the sprites, and

has exactly the same dimensions as the canvas. You can think of the

stage as a big, invisible sprite, the same size as the canvas, that contains

all the sprites in your game, as well as any containers those sprites

might be grouped in (Like the gameScene). putCenter works by

centering the treasure inside the stage, and then offsetting its

x position by 220 pixels. Here's the format for using putCenter:

anySprite.putCenter(anyOtherSprite, xOffset, yOffset);You can use the other put methods in the same way. For example, if

you wanted to position a sprite directly to the left of another

sprite, without any offset, you could use putLeft, like this:

spriteOne.putLeft(spriteTwo);This would place spriteTwo directly to the left of spriteOne, and

align it vertically .You'll see many examples of how to use these put methods throughout

these tutorials.

Before we continue, there's one small detail you need to notice. The

code that creates the sprites also adds a pickedUp property to the

treasure sprite:

treasure.pickedUp = false;You'll see how we're going to use treasure.pickedUp later in the game logic to help us determine the

progress of the game. You can dynamically assign any custom properties or methods to sprites like this, if you need to.

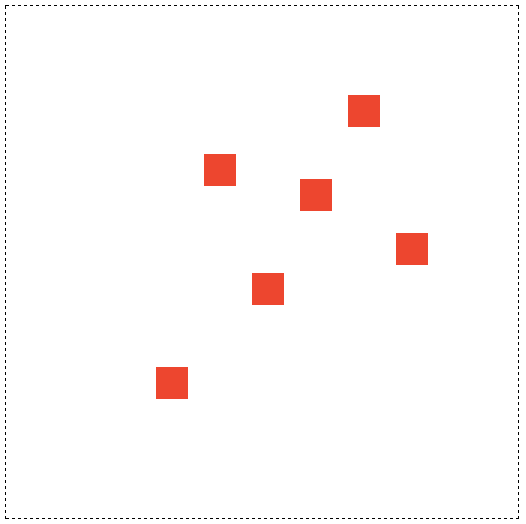

There are 6 enemies sprites (red squares) in Treasure Hunter. They're

spaced evenly horizontally but but have random initial vertical

positions. All the enemies sprites are created in a for loop using

this code in the setup function:

//Make the enemies

let numberOfEnemies = 6,

spacing = 48,

xOffset = 150,

speed = 2,

direction = 1;

//An array to store all the enemies

enemies = [];

//Make as many enemies as there are `numberOfEnemies`

for (let i = 0; i < numberOfEnemies; i++) {

//Each enemy is a red rectangle

let enemy = g.rectangle(32, 32, "red");

//Space each enemey horizontally according to the `spacing` value.

//`xOffset` determines the point from the left of the screen

//at which the first enemy should be added.

let x = spacing * i + xOffset;

//Give the enemy a random y position

let y = g.randomInt(0, g.canvas.height - enemy.height);

//Set the enemy's direction

enemy.x = x;

enemy.y = y;

//Set the enemy's vertical velocity. `direction` will be either `1` or

//`-1`. `1` means the enemy will move down and `-1` means the enemy will

//move up. Multiplying `direction` by `speed` determines the enemy's

//vertical direction

enemy.vy = speed * direction;

//Reverse the direction for the next enemy

direction *= -1;

//Push the enemy into the `enemies` array

enemies.push(enemy);

//Add the enemy to the `gameScene`

gameScene.addChild(enemy);

}Here's what this code produces:

The code gives each of the enemies a random y position with the help

of Hexi's randomInt method:

let y = g.randomInt(0, g.canvas.height - enemy.height);randomInt will give you a random number between any two integers that you

provide in the arguments. (If you need a random decimal number, use

randomFloat instead).

All sprites have properties called vx and vy. They determine the

speed and direction that the sprite will move in the horizontal

direction (vx) and vertical direction (vy). The enemies in

Treasure Hunter only move up and down, so they just need a vy value.

Their vy is speed (2) multiplied by direction (which will be

either 1 or -1).

enemy.vy = speed * direction;If direction is 1, the enemy's vy will be 2. That means the

enemy will move down the screen at a rate of 2 pixels per frame. If

direction is -1, the enemy's speed will be -2. That means the

enemy will move up the screen at 2 pixels per frame.

After the enemy's vy is set, direction is reversed so that the next

enemy will move in the opposite direction.

direction *= -1;You can see that each enemy that's created is pushed into an array

called enemies.

enemies.push(enemy);Later in the code you'll see how we'll access all the enemies in this array to figure out if they're touching the player.

You'll notice that when the player touches one of the enemies, the width of the health bar at the top right corner of the screen decreases.

How was this health bar made? It's just two rectangle sprites at the same

position: a black rectangle behind, and a green rectangle in front. They're grouped

together to make a single compound sprite called healthBar. The

healthBar is then added to the gameScene.

//Create the health bar

let outerBar = g.rectangle(128, 16, "black"),

innerBar = g.rectangle(128, 16, "yellowGreen");

//Group the inner and outer bars

healthBar = g.group(outerBar, innerBar);

//Set the `innerBar` as a property of the `healthBar`

healthBar.inner = innerBar;

//Position the health bar

healthBar.x = g.canvas.width - 148;

healthBar.y = 16;

//Add the health bar to the `gameScene`

gameScene.addChild(healthBar);You can see that a property called inner has been added to the

healthBar. It just references the innerBar (the green rectangle) so that

it will be convenient to access later.

healthBar.inner = innerBar;You don't have to do this; but, hey why not! It means that if you

want to control the width of the innerBar, you can write some smooth code

that looks like this:

healthBar.inner.width = 30;That's pretty neat and readable, so we'll keep it!

If the player's health drops to zero, or the player manages to carry the treasure to the exit, the game ends and the game over screen is displayed. The game over scene is just some text that displays "You won!" or "You lost!" depending on the outcome.

How was this made? The text is made with a text sprite.

let anyText = g.text(

"Hello!", "CSS font properties", "fillColor", xPosition, yPosition

);The first argument, "Hello!" in the above example, is the text content

you want to display. Use the content property to change the text

sprite's content later.

anyText.content = "Some new content";Here's how the game over message text is created in the setup

function.

//Add some text for the game over message

message = g.text("Game Over!", "64px Futura", "black", 20, 20);

message.x = 120;

message.y = g.canvas.height / 2 - 64;Next, a new group is created called gameOverScene. The message text

is added to it. The gameOverScene's visible property is set to

false so that it's not visible when the game first starts.

//Create a `gameOverScene` group and add the message sprite to it

gameOverScene = g.group(message);

//Make the `gameOverScene` invisible for now

gameOverScene.visible = false;At the end of the game we'll set the gameOverScene's visible

property to true to display the text message. We'll also set the

gameScene's visible property to false so that all the game

sprites are hidden.

You control the player (the blue square) with the keyboard arrow keys.

Hexi has a built-in arrowControl method that lets you quickly add

arrow key interactivity to games. Supply the sprite you want to move as

the first argument, and the number of pixels per frame that it

should move as the second argument. Here's how the arrowControl

method is used to help make the player character move 5 pixels per

frame when the arrow keys are pressed.

g.arrowControl(player, 5);Using arrowControl is an easy and fast way to implement keyboard

interactivity, but usually need finer control over what happens when

keys are pressed. Hexi has a built-in keyboard method that lets you define custom keys.

let customKey = g.keyboard(asciiCode);Supply the ascii key code number for key you want to to use as the first argument.

All these keys have press and

release methods that you can define. Here's how you could optionally create and use these keyboard objects to help move the player character in

Treasure Hunter. (You would define this code in the setup function.):

//Create some keyboard objects using Hexi's `keyboard` method.

//You would usually use this code in the `setup` function.

//Supply the ASCII key code value as the single argument

let leftArrow = g.keyboard(37),

upArrow = g.keyboard(38),

rightArrow = g.keyboard(39),

downArrow = g.keyboard(40);

//Left arrow key `press` method

leftArrow.press = () => {

//Change the player's velocity when the key is pressed

player.vx = -5;

player.vy = 0;

};

//Left arrow key `release` method

leftArrow.release = () => {

//If the left arrow has been released, and the right arrow isn't down,

//and the player isn't moving vertically:

//Stop the player

if (!rightArrow.isDown && player.vy === 0) {

player.vx = 0;

}

};

//The up arrow

upArrow.press = () => {

player.vy = -5;

player.vx = 0;

};

upArrow.release = () => {

if (!downArrow.isDown && player.vx === 0) {

player.vy = 0;

}

};

//The right arrow

rightArrow.press = () => {

player.vx = 5;

player.vy = 0;

};

rightArrow.release = () => {

if (!leftArrow.isDown && player.vy === 0) {

player.vx = 0;

}

};

//The down arrow

downArrow.press = () => {

player.vy = 5;

player.vx = 0;

};

downArrow.release = () => {

if (!upArrow.isDown && player.vx === 0) {

player.vy = 0;

}

};You can see that the value of the player's vx and vy properties is

changed depending on which keys are being pressed or released.

A positive vx value will make the player move right, a negative

value will make it move left. A positive vy value will make the

player move down, a negative value will make it move up.

The first argument is the sprite you want to control: player. The

second argument is the number of pixels that the sprite should move each frame: 5.

The last four arguments are the ascii key code numbers for the top,

right, bottom and left keys. (You can remember this because their

order is listed clockwise, starting from the top.)

The game state is the function that Hexi is currently running. When

Hexi first starts, it runs the setup function (or whatever other

function you specify in Hexi's constructor function arguments.) If you

want to change the game state, assign a new function to Hexi's state

property. Here's how:

g.state = anyFunction;In Treasure Hunter, when the setup function is finished, the game

state is set to play:

g.state = play;This makes Hexi look for and run a function called play. By default,

any function assigned to the game state will run in a continuous loop, at

60 frames per second. (You can change the frame rate at any time by setting Hexi's

fps property). Game logic usually runs in a continuous loop, which

is known as the game loop. Hexi handles the loop management for you,

so you don't need to worry about how it works.

(In case you're curious, Hexi uses

a requestAnimationFrame loop with a fixed logic time step and variable rendering time. It

also does sprite position interpolation to smoothe out any inconsistent

spikes in the frame rate. It runs Smoothie

under-the-hood to do all this, so you can use any of Smoothie's properties to

fine-tune your Hexi application game loops for the best possible effect.)

If you ever need to pause the loop, just use Hexi's pausemethod, like

this:

g.pause();You can start the game loop again with the resume method, like this:

g.resume();Now let's find out how Treasure Hunter's play function works.

As you've just learned, everything in the play function runs in a

continuous loop.

function play() {

//This code loops from top to bottom 60 times per second

}This is where all the game logic happens. It's the fun part,

so let's find out what the code inside the play function does.

Treasure Hunter uses Hexi's move method inside the play function to move the sprites in the

game.

g.move(player);This is the equivalent of writing code like this:

player.x += player.vx;

player.y += player.vy;It just updates the player's x and y position by adding its vx

and vy velocity values. (Remember, those values were

set by the key press and release methods.) Using move just saves

you from having to type-in and look-at this very standard boilerplate

code.

You can also move a whole array of sprites with one line of code by supplying the array as the argument.

g.move(arrayOfSprites);So now you can easily move the player, but what happens when the player reaches the edges of the screen?

Use Hexi's contain method to keep sprites inside the boundaries of

the screen.

g.contain(player, g.stage);The first argument is the sprite you want to contain, and the second

argument is any JavaScript object with an x, y, width, and

height property.

As you learnt earlier, stage is the root container object for all Hexi's sprites, and it has

the same width and height as the canvas.

But you can alternatively supply the contain method with a custom

object to do the same thing. Here's how:

g.contain(

player,

{

x: 0,

y: 0,

width: 512,

height: 512

}

);This will contain the player sprite to an area defined by the

dimensions of the object. This is really convenient if you want to

precisely fine-tune the area in which the object should be contained.

contain has an extra useful feature. If the sprite reaches one of

the containment edges, contain will return a JavaScript Set that tells you

which edge it reached: "top", "right", "bottom", or "left". Here's how

you could use this feature to find out which edge of the canvas the

sprite is touching:

let playerHitsEdges = g.contain(player, g.stage);

if(playerHitsEdges) {

//Find out on which side the collision happened

let collisionSide;

if (playerHitsEdges.has("left")) collisionSide = "left";

if (playerHitsEdges.has("right")) collisionSide = "right";

if (playerHitsEdges.has("top")) collisionSide = "top";

if (playerHitsEdges.has("bottom")) collisionSide = "bottom";

//Display the result in a text sprite

message.content = `The player hit the ${collisionSide} of the canvas`;

} When the player hits any of the enemies, the width of the health bar decreases and the player becomes semi-transparent.

How does this work?

Hexi has a full suite of useful 2D geometric and tile-based collision detection methods. Hexi implements the Bump collision module so all of Bump's collision methods work with Hexi.

Treasure Hunter only uses one of these collision methods:

hitTestRectangle. It takes two rectangular sprites and tells you

whether they're overlapping. It will return true if they are, and

false if they aren't.

g.hitTestRectangle(spriteOne, spriteTwo);Here's how the code in the play function uses hitTestRectangle to

check for a collision between any of the enemies and the player.

//Set `playerHit` to `false` before checking for a collision

let playerHit = false;

//Loop through all the sprites in the `enemies` array

enemies.forEach(enemy => {

//Move the enemy

g.move(enemy);

//Check the enemy's screen boundaries

let enemyHitsEdges = g.contain(enemy, g.stage);

//If the enemy hits the top or bottom of the stage, reverse

//its direction

if (enemyHitsEdges) {

if (enemyHitsEdges.has("top") || enemyHitsEdges.has("bottom")) {

enemy.vy *= -1;

}

}

//Test for a collision. If any of the enemies are touching

//the player, set `playerHit` to `true`

if (g.hitTestRectangle(player, enemy)) {

playerHit = true;

}

});

//If the player is hit...

if (playerHit) {

//Make the player semi-transparent

player.alpha = 0.5;

//Reduce the width of the health bar's inner rectangle by 1 pixel

healthBar.inner.width -= 1;

} else {

//Make the player fully opaque (non-transparent) if it hasn't been hit

player.alpha = 1;

}This bit of code creates a variable called playerHit, which is

initialized to false just before the forEach loop checks all the

enemies for a collision.

let playerHit = false;(Because the play function runs 60 times per second, playerHit

will be reinitialized to false on every new frame.)

If hitTestRectangle returns true, the forEach loop sets

playerHit to true.

if(g.hitTestRectangle(player, enemy)) {

playerHit = true;

}If the player has been hit, the code makes the player semi-transparent by

setting its alpha value to 0.5. It also reduces the width of the

healthBar's inner sprite by 1 pixel.

if(playerHit) {

//Make the player semi-transparent

player.alpha = 0.5;

//Reduce the width of the health bar's inner rectangle by 1 pixel

healthBar.inner.width -= 1;

} else {

//Make the player fully opaque (non-transparent) if it hasn't been hit

player.alpha = 1;

}You can set the alpha property of sprites to any value between 0

(fully transparent) to 1 (fully opaque). A value of 0.5 makes it

semi-transparent.b (Alpha is a

well-worn graphic design term that just means transparency.)

This bit of code also uses the move method to move the enemies, and

contain to keep them contained inside the canvas. The code also uses

the return value of contain to find out if the enemy is hitting the

top or bottom of the canvas. If it hits the top or bottom, the enemy's direction is

reversed with the help of this code:

//Check the enemy's screen boundaries

let enemyHitsEdges = g.contain(enemy, g.stage);

//If the enemy hits the top or bottom of the stage, reverse

//its direction

if (enemyHitsEdges) {

if (enemyHitsEdges.has("top") || enemyHitsEdges.has("bottom")) {

enemy.vy *= -1;

}

}Multiplying the enemy's vy (vertical velocity) value by negative 1

makes it go in the opposite direction. It's a really simple bounce

effect.

If the player touches the treasure (the yellow square), the chimes

sound plays. The player can then

carry the treasure to the exit. The treasure is centered over the player and

moves along with it.

Here's the code from the play function that achieves these effects.

//Check for a collision between the player and the treasure

if (g.hitTestRectangle(player, treasure)) {

//If the treasure is touching the player, center it over the player

treasure.x = player.x + 8;

treasure.y = player.y + 8;

if(!treasure.pickedUp) {

//If the treasure hasn't already been picked up,

//play the `chimes` sound

chimes.play();

treasure.pickedUp = true;

};

}You can see that the code uses hitTestRectangle inside an if

statement to test for a collision between the player and the treasure.

if (g.hitTestRectangle(player, treasure)) {If it's true, the treasure is centered over the player.

treasure.x = player.x + 8;

treasure.y = player.y + 8;If treasure.pickedUp is false, then you know that the treasure hasn't already been

picked up, and you can play the chimes sound:

chimes.play();In addition to play Hexi's sound objects also have a few more methods that you can use to control them:

pause, restart and playFrom. (Use playFrom to start playing

the sound from a specific second in the sound file, like this:

soundObject.playFrom(5). This will make the sound start playing from

the 5 second mark.)

You can also set the sound object's volume by assigning

a value between 0 and 1. Here's how to set the volume to mid-level

(50%).

soundObject.volume = 0.5;You can set the sound object's pan by assigning a value between -1 (left speaker)

to 1 (right speaker). A pan value of 0 makes the sound equal volume in

both speakers. Here's how you could set the pan to be slightly more

prominent in the left speaker.

soundObject.pan = -0.2;If you want to make a sound repeat continuously, set its loop property to true.

soundObject.loop = true;Hexi implements the Sound.js module to control sounds, so you can use any of Sound.js's properties and methods in your Hexi applications.

Because you don't want to play the chimes sound more than once after

the treasure has been picked up, the code sets treasure.pickedUp to

true just after the sound plays.

treasure.pickedUp = true;Now that the player has picked up the treasure, how can you check for the end of the game?

There are two ways the game can end. The player's health can run out,

in which case the game is lost. Or, the player can successfully carry

the treasure to the exit, in which case the game is won. If either of

these two conditions are met, the game's state is set to end and

the message text's content displays the outcome. Here's the last

bit of code in the play function that does this:

//Does the player have enough health? If the width of the `innerBar`

//is less than zero, end the game and display "You lost!"

if (healthBar.inner.width < 0) {

g.state = end;

message.content = "You lost!";

}

//If the player has brought the treasure to the exit,

//end the game and display "You won!"

if (g.hitTestRectangle(treasure, exit)) {

g.state = end;

message.content = "You won!";

}The end function is really simple. It just hides the gameScene and

displays the gameOverScene.

function end() {

gameScene.visible = false;

gameOverScene.visible = true;

}And that's it for Treasure Hunter! Before you continue, try making your own game from scratch using some of these same techniques. When you're ready, read on!

There are three main ways you can use images in your Hexi games.

- Use individual image files for each sprite.

- Use a texture atlas. This is a single image file that includes sub-images for each sprite in your game. The image file is accompanied by a matching JSON data file that describes the name, size and location of each sub-image.

- Use a tileset (also known as a spritesheet). This is also a single image file that includes sub-images for each sprite. However, unlike a texture atlas, it doesn't come with a JSON file describing the sprite data. Instead, you need to specify the size and location of each sprite in your game code with JavaScript. This can have some advantages over a texture atlas in certain circumstances.

All three ways of making image sprites use Hexi's sprite method.

Here's the simplest way of using it to make an image sprite.

let imageSprite = g.sprite("images/theSpriteImage.png");In this next section we'll update Treasure Hunter with image sprites, and you'll learn all three ways of adding images to your games.

(All the images in this section were created by Lanea Zimmerman. You can find more of her artwork here. Thanks, Lanea!)

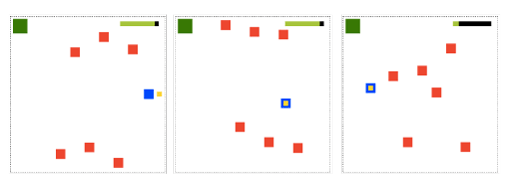

Open and play the next version of Treasure Hunter:

02_treasureHunterImages.html (you'll find it in the tutorials

folder.) It plays exactly the same as the first version, but all the

colored squares have been replaced by images.

(Click the image and follow the link to play the game.) Take a look at the source code, and you'll notice that the game logic and structure is exactly the same as the first version of the game. The only thing that's changed is the appearance of the sprites. How was this done?

Each sprite in the game uses an individual PNG image file. You'll find

all the images in the tutorials' images sub-folder.

Before you can use them to make sprites, you need to pre-load them into

Hexi's assets. The easiest way to do this is to list the image names,

with their full file paths, in Hexi's assets array when you first

initialize the engine. Create an array called thingsToLoad, list the

file names, as strings, that you want to load. Then supply that array

as the hexi method's fourth argument. Here's how:

//An array that contains all the files you want to load

let thingsToLoad = [

"images/explorer.png",

"images/dungeon.png",

"images/blob.png",

"images/treasure.png",

"images/door.png",

"sounds/chimes.wav"

];

//Create a new Hexi instance, and start it

let g = hexi(512, 512, setup, thingsToLoad);

//Start Hexi

g.start();(If you open up the JavaScript console in the web browser, you can monitor the loading progress of these assets.)

Now you can access any of these images in your game code like this:

g.image("images/blob.png")Although pre-loading the images and other assets is the simplest way

to get them into your game, you can also load assets at any other time

using the loader object and its methods. As I mentioned earlier,

the loader is just an alias for Pixi's loader that's running

under-the-hood, and you can learn more about how to use it here.

Now that you've loaded the images into the game, let's find out how to use them to make sprites.

Create an image sprite using the sprite method using the same format you learnt

earlier. Here's how to create a sprite using the dungeon.png image.

(dungeon.png is a 512 by 512 pixel background image.)

dungeon = g.sprite("images/dungeon.png");That's all! Now instead of displaying as a simple colored rectangle,

the sprite will be displayed as a 512 by 512 image. There's no need

to specify the width or height, because Hexi figures that our for you

automatically based on the size of the image. You can use all the other

sprite properties, like x, y, width, and height, just as you

would with ordinary rectangle sprites.

Here's the code from the setup function that creates the dungeon

background, exit door, player and treasure, and adds them all to the

gameScene group.

//The dungeon background

dungeon = g.sprite("images/dungeon.png");

//The exit door

exit = g.sprite("images/door.png");

exit.x = 32;

//The player sprite

player = g.sprite("images/explorer.png");

player.x = 68;

player.y = g.canvas.height / 2 - player.halfWidth;

//Create the treasure

treasure = g.sprite("images/treasure.png");

//Position it next to the left edge of the canvas

//g.stage.putCenter(treasure, 208, 0);

//Create a `pickedUp` property on the treasure to help us Figure

//out whether or not the treasure has been picked up by the player

treasure.pickedUp = false;

//Create the `gameScene` group and add the sprites

gameScene = g.group(dungeon, exit, player, treasure);(As a slightly more efficient improvement to the

original version of this code, group creates the gameScene and groups

the sprites in a single step.)

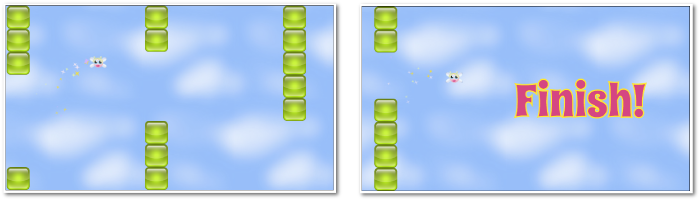

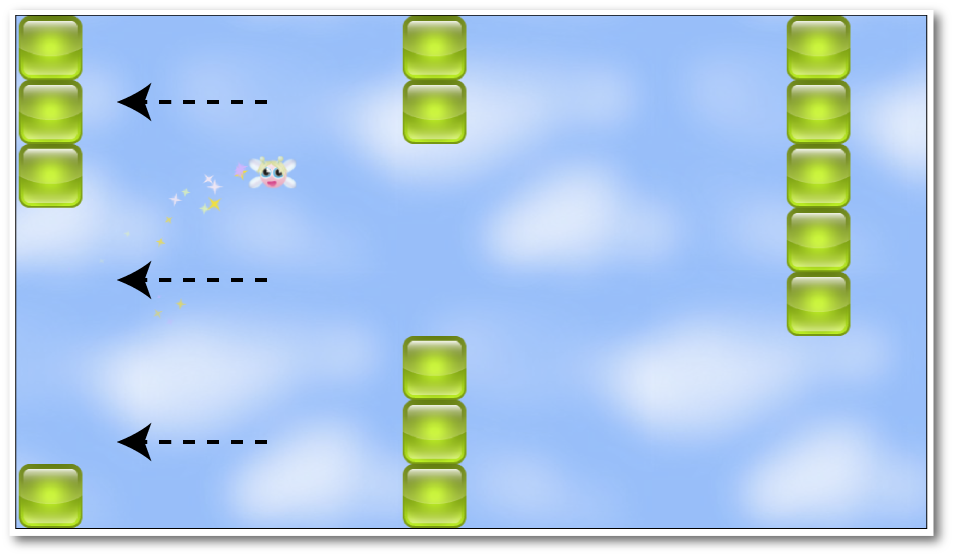

Look familiar? That's right, the only code that has changed are the lines that create the sprites. This modularity is a feature of Hexi that lets you create quick game prototypes using simple shapes that you can easily swap out for detailed images as your game ideas develops. The rest of the code in the game can remain as-is.

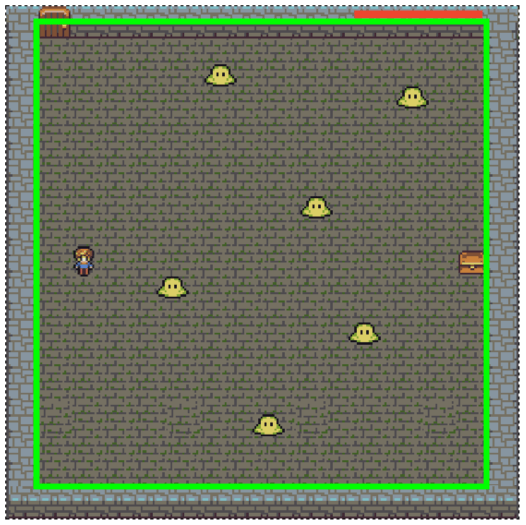

One small improvement that was made to this new version Treasure Hunter is the new way that the sprites are contained inside the walls of the dungeon. They're contained in such a way that naturally matches the 2.5D perspective of the artwork, as shown by the green square in this screen shot:

This is a very easy modification to make. All you need to do is supply

the contain method with a custom object that defines the size and

position of the containing rectangle. Here's how:

g.contain(

player,

{

x: 32, y: 16,

width: g.canvas.width - 32,

height: g.canvas.height - 32

}

);Just tweak the x, y, width and height values so that the

containing area looks natural for the game you're making.

If you’re working on a big, complex game, you’ll want a fast and efficient way to work with images. A texture atlas can help you do this. A texture atlas is actually two separate files that are closely related:

- A single PNG tileset image file that contains all the images you want to use in your game. (A tileset image is sometimes called a spritesheet.)

- A JSON file that describes the size and position of those sub-images in the tileset.

Using a texture atlas is a big time saver. You can arrange the tileset’s sub-images in any order and the JSON file will keep track of their sizes and positions for you. This is really convenient because it means the sizes and positions of the sub-images aren’t hard-coded into your game program. If you make changes to the tileset, like adding images, resizing them, or removing them, just re-publish the JSON file and your game will use that updated data to display the images correctly. If you’re going to be making anything bigger than a very small game, you’ll definitely want to use a texture atlas.

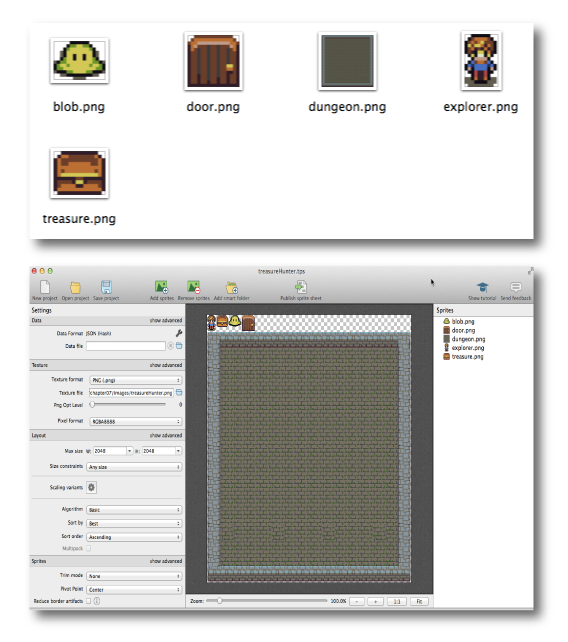

The de-facto standard for tileset JSON data is the format that is output by a popular software tool called Texture Packer (Texture Packer's "Essential" license is free ). Even if you don’t use Texture Packer, similar tools like Shoebox output JSON files in the same format. Let’s find out how to use it to make a texture atlas with Texture Packer, and how to load it into a game.

You first need individual PNG images for each image in your game. You've already got them for Treasure Hunter, so you're all set. Open Texture Packer and choose the {JS} configuration option. Drag your game images into its workspace. You can also point Texture Packer to any folder that contains your images. Texture Packer will automatically arrange the images on a single tileset image, and give them names that match their original image file names. It will give them a 2 pixel padding by default.

Each of the sub-images in the atlas is called a frame. Although it's just one big image, the texture atlas has 5 frames. The name of each frame is the same its original PNG file name: "dungeon.png", "blob.png", "explorer.png", "treasure.png" and "door.png". These frames names are used to help the atlas reference each sub-image.

When you’re done, make sure the Data Format is set to JSON (Hash) and

click the Publish button. Choose the file name and location, and save the

published files. You’ll end up with a PNG file and a JSON file. In

this example my file names are treasureHunter.json and

treasureHunter.png. To make

your life easier, just keep both files in your project’s images

folder. (Think of the JSON file as extra metadata for the image file.)

Texture Packer can often be a pain to use, because you need to get all these settings just right for it to publish properly without telling you there are errors. And, it will try to trick you into upgrading to the paid version by using default settings not supported by the free version. So you need to explicitly turn these off (as I've described above) for it to work without errors. Still, it's worth the effort in the end - so keep trying and post an issue in this repository if you get impossibly stuck!

To load the texture atlas into your game, just include the JSON file in Hexi's assets array when you initialize the game.

let thingsToLoad = [

"images/treasureHunter.json",

"sounds/chimes.wav"

];

let g = hexi(512, 512, setup, thingsToLoad);

g.scaleToWindow();

g.start();That's all! You don't have to load the PNG file - Hexi does that automatically in the background. The JSON file is all you need to tell Hexi which tileset frame (sub-image) to display.

Now if you want to use a frame from the texture atlas to make a sprite, you can do it like this:

anySprite = g.sprite("frameName.png");Ga will create the sprite and display the correct image from the texture atlas's tileset.

Here's how to you could create the sprites in Treasure Hunter using texture atlas frames:

//The dungeon background

dungeon = g.sprite("dungeon.png");

//The exit door

exit = g.sprite("door.png");

exit.x = 32;

//The player sprite

player = g.sprite("explorer.png");

player.x = 68;

player.y = g.canvas.height / 2 - player.halfWidth;

//Create the treasure

treasure = g.sprite("treasure.png");Hexi knows that those are texture atlas frame names, not individual images, and it displays them directly from the tileset.

If you ever need to access the texture atlas's JSON file in your game, you can get it like this:

jsonFile = g.json("jsonFileName.json");Take a look at treasureHunterAtlas.js file in the tutorials folder

to see a working example of how to load a texture atlas and use it to

make sprites.

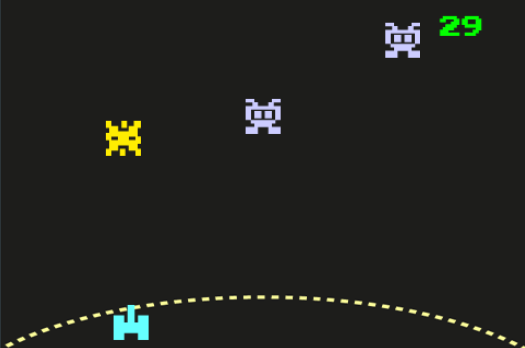

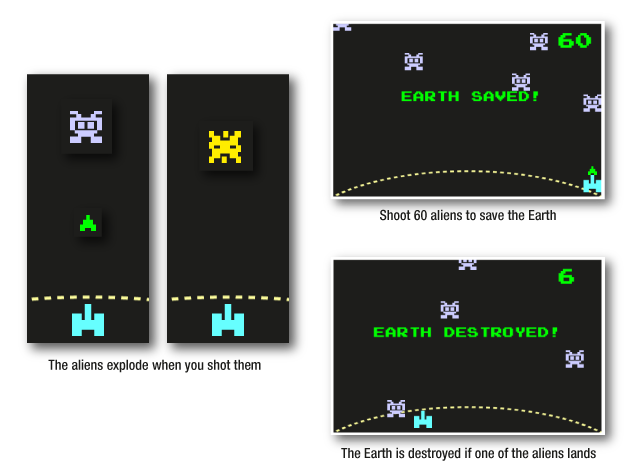

The next example game in this series of tutorials is Alien Armada. Can you destroy 60 aliens before one of them lands and destroys the Earth? Click the image link below to play the game:

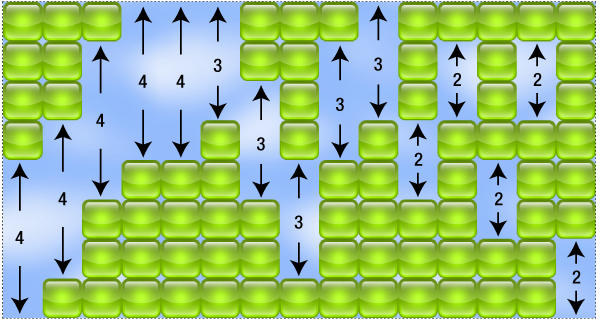

Use the arrow keys to move and press the space bar to shoot. The aliens descend from the top of the screen with increasing frequency as the game progresses. Here's how the game is played:

Alien Armada illustrates some new techniques that you'll definitely want to use in your games:

- Load and use custom fonts.

- Display a loading progress bar while the game assets load.

- Shoot bullets.

- Create sprites with multiple image states.

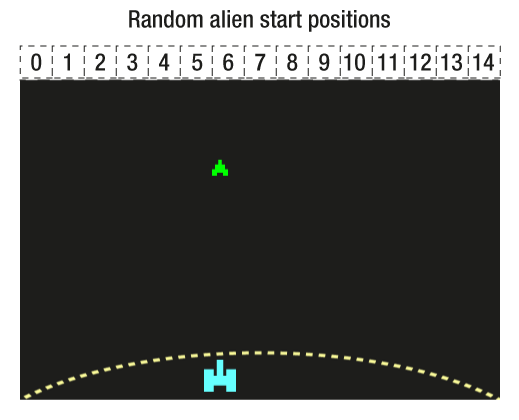

- Generate random enemies.

- Remove sprites from a game.

- Display a game score.

- Reset and restart a game.

You'll find the fully commented Alien Armada source code in the

tutorials folder. Make sure to take a look at it so that you can see

all of this code in its proper context. Its general structure is identical

to Treasure Hunter, with the addition of these new techniques. Let's

find out how they were implemented.

Alien Armada uses a custom font called emulogic.ttf to display the

score at the top right corner of the screen. The font file is

preloaded with the rest of the asset files (sounds and images) in the assets array that

initializes the game.

let thingsToLoad = [

"images/alienArmada.json",

"sounds/explosion.mp3",

"sounds/music.mp3",

"sounds/shoot.mp3",

"fonts/emulogic.ttf" //<- The custom font

];

let g = hexi(480, 320, setup, thingsToLoad, load);

g.scaleToWindow();

g.start();To use the font, create a text sprite in the game's setup

function. The text method's second argument is a

string that describes the font's point size and name: "20px emulogic".

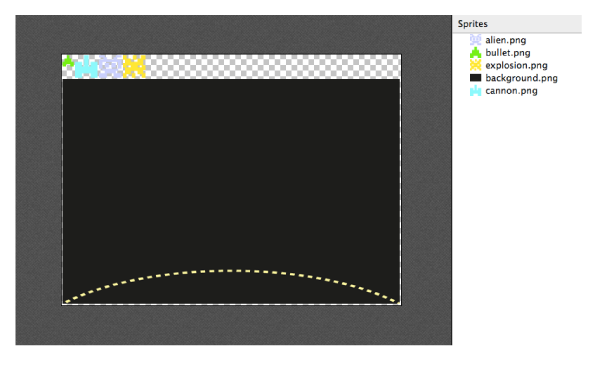

scoreDisplay = g.text("0", "20px emulogic", "#00FF00", 400, 10);You can and load and use any fonts in TTF, OTF, TTC or WOFF format.