- We try to simplify Dung-Style Argumentation Frameworks (AFs) by partitioning arguments into clusters

- We implement conflict-free, admissible and stable semantics for clustered arguments

- We implement a method to identify spurious partitions which do not preserve the semantics of the original AF

- We implement methods to automatically compute non-spurious partitions

- All implementations are done in Answer Set Programming (ASP) and Python 3

The below code was developed in Python 3.10.8 and Clingo 5.5.1 . Please consult to the installation documents for setup:

- Python 3 https://www.python.org/downloads/

- Clingo CLI & Python library https://potassco.org/clingo/

Below is an overview of the features provided in this repository and how to use them. This is meant as a quick reference. Everything is explained in more detail below.

Computing classical extensions

clingo <example>.lp <semantic>.lp 0

Computing clustered extensions

clingo <example>.lp <example-map>.lp to-clustered-af.lp <clustered-semantic>.lp

Checking whether an extension is spurious

clingo <example>.lp <example-map>.lp <example-clustered-extension>.lp to-clustered-af.lp <classical-semantics>.lp <clustered-semantic>.lp spurious.lp 0

Finding spurious extensions for an abstraction mapping

python find_spurious.py cf|admissible|stable <example>.lp <example-mapping>.lp

Abstraction refinement based on spurious clustered extensions

python refine-spurious-guided.py cf|admissible|stable <example>.lp <example-mapping-initial>.lp

Abstraction refinement based on exhaustive search

python refine-exhaustive.py cf|admissible|stable <example>.lp <example-mapping-initial>.lp

... to see all options

python refine-exhaustive.py -h

In this chapter we recite the central definitions from 1.

Given a finite set of arguments

We consider conflict-free, admissible and stable extensions

(respectively

$cf(F) = \{ S \subseteq A \mid \forall a,b \in S : (a,b) \not \in R \}$ $adm(F) = \{ S \in cf(F) \mid S \subseteq \mathcal F _F (S) \}$ $stb(F) = \{ S \in cf(F) \mid \forall a \in A \setminus S : \exists (b,a) \in R : b \in S \}$

We will refer to these definition as the "classical" or "concrete" ones, as opposed to the "clustered" ones defined next.

Based on a classical

For convenience we extend

$m(S) = \{ m(a) \mid a \in A \}$ $m(F) = \hat F = (\hat A, \hat R)$

The mapping

We define conflict-free, admissible and stable extensions for the clustered AF

(respectively

$\hat {cf} ( \hat F) = \{ \hat E \subseteq \hat A \mid \forall \hat a, \hat b \in single(\hat E): (\hat a, \hat b) \not \in \hat R \} $ $\hat {adm} ( \hat F) = \{ \hat E \in \hat {cf} ( \hat F) \mid \forall \hat a \in single(\hat E) : (\hat b, \hat a) \in \hat R \rightarrow \exists \hat c \in \hat E : (\hat c, \hat b) \in \hat R \} $ $\hat {stb} ( \hat F) = \{ \hat E \in \hat {cf} ( \hat F) \mid ( \hat b \not \in \hat E \rightarrow \exists \hat a \in \hat E : (\hat a, \hat b) \in \hat R) \land (\forall \hat a \in \hat E : (\not \exists \hat x \in \hat E : (\hat x, \hat a) \in \hat R) \land (\hat a, \hat b) \in \hat R \land \hat b \in single(\hat A) ) \rightarrow \hat b \not \in \hat E \}$

Finally, for some

-

$\hat E \in \hat \sigma (m(F))$ is spurious w.r.t.$F$ under$\sigma$ if$\not \exists E \in \sigma (F) : m(E) = \hat E$ -

$m(F)$ under$\hat \sigma$ is faithful w.r.t.$F$ under$\sigma$ if there is no spurious$\hat E \in \hat \sigma ( \hat m(F) )$ w.r.t$F$ under$\sigma$ .

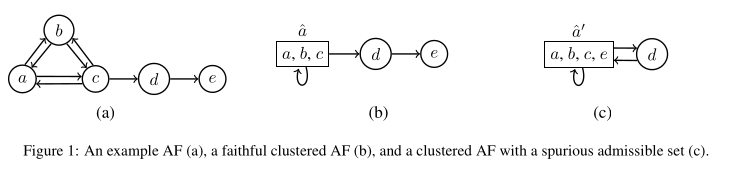

We use several examples from Saribatur and Wallner 20211.

-

Figure 1 in the paper can be found as

examples/e1...in the code. The meaning of the different.lpfiles are explained below.

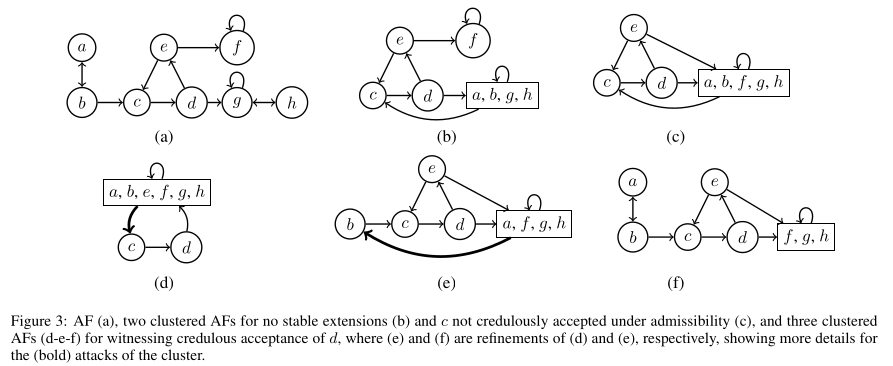

-

Figure 3 in the paper can be found as

examples/e3...in the code. The meaning of the different.lpfiles are explained below.

-

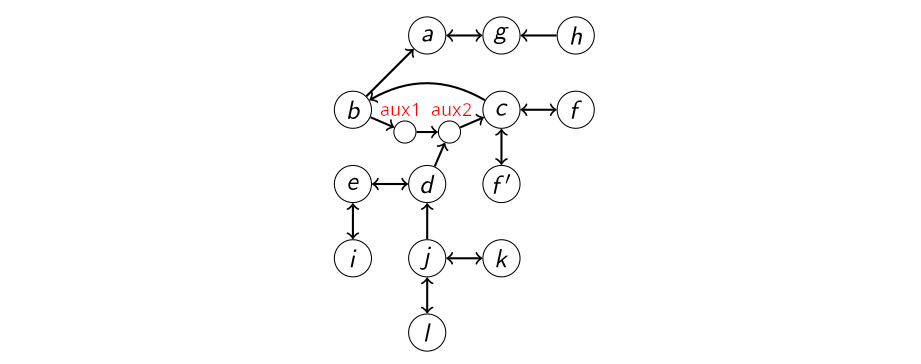

The Simonshaven case from Prakken 20192 serves as a practical application of the abstraction techniques. It was converted into a classical-AF format by Saribatur and Wallner in their lecture notes (no public reference).

The semantics were implemented in Answer Set Programming (ASP).

The ASP encodings for

-

$\pi_F = \{ \textbf{arg} (a). \mid a \in A \} \cup \{ \textbf{att} (a,b). \mid (a,b) \in R \}$ . $\pi_m = \{ \textbf{abs\_map} (a, \hat a). \mid a \in A, m(a) = \hat a \}$

Programs of this type can be found in the /examples and /tests directories.

The induced

abs_arg(X) :- abs_map(_,X).

singleton(X) :- 1 = #count { Y : abs_map(Y,X) }, abs_arg(X).

abs_att(X',Y') :- att(X,Y), abs_map(X,X'), abs_map(Y,Y').

The above program can be found in to-clustered-af.lp.

In the text we refer to it also as

The classical semantics are defined as usual3,

where

We will refer to the ASP encodings of the

classical semantics as

/semantics.

The extensions are computed as follows:

$\sigma (F) \cong \mathcal{AS} ( \pi_F \cup \pi_{\sigma} )$ $\hat \sigma (m(F)) \cong \mathcal{AS} ( \pi_F \cup \pi_m \cup \pi_{m(F)} \cup \pi_{\hat \sigma} )$

The ASP implementation of these semantics are described in Saribatur and Wallner 20211. For the Clustered Conflict-Free case we have:

{ abs_in(X) : abs_arg(X) }.

:- abs_in(X), abs_in(Y), abs_att(X,Y), singleton(X), singleton(Y).

For the Clustered Admissible semantics we extend the above by:

abs_defeated(X) :- abs_in(Y), abs_att(Y,X), singleton(Y).

{ abs_defeated(X) } :- abs_in(Y), abs_att(Y,X), not singleton(Y).

:- abs_in(X), abs_att(Y,X), not abs_defeated(Y), singleton(X).

These semantics were the first implementation task for this project. It was implemented as follows:

{ abs_in(X) : abs_arg(X) }.

:- abs_in(X), abs_in(Y), abs_att(X,Y), singleton(X), singleton(Y).

abs_in(Y) :- abs_arg(Y), not abs_in(X) : abs_att(X,Y).

abs_defeated(Y) :- abs_in(X), abs_att(X,Y).

not abs_in(B) :- abs_in(A), not abs_defeated(A), abs_att(A,B), singleton(B).

The third line was inspired by the ASPARTIX-Implementation of the classical stable semantics3.

To ensure correctness, we tested the stable semantics with several instances:

tests/cstable-1ensures the clustered semantics reduce to the classical ones when every clustered argument is singleton/tests/cstable-2ensures that not-attacked clusters are always accepted, always-attacked singletons are never accepted and always-attacked clusteres can be both accepted or not./tests/cstable-3and/tests/cstable-4have different concrete AF's but their mapping induces the same clustered AF. Thus, their clustered semantics should yield the same extensions.

To run the tests, execute in a terminal:

. 1-clustered-stable-semantics-examples.sh

Given some

Recall the ASP encodings defined above:

-

$\pi_F = \{ \textbf{arg} (a). \mid a \in A \} \cup \{ \textbf{att} (a,b). \mid (a,b) \in R \}$ . $\pi_m = \{ \textbf{abs\_map} (a, \hat a). \mid a \in A, m(a) = \hat a \}$ -

$\pi_{m(F)}$ to deduce$\textbf{abs\_arg}/1$ ,$\textbf{singleton}/1$ and$\textbf{abs\_att}/2$ . -

$\pi_{\sigma}$ to deduce$\textbf{in}/1$ -

$\pi_{\hat \sigma}$ to deduce$\textbf{abs\_in}/1$

First consider the program

Second, we need to eliminate combinations of

:- abs_in(X'), 0 = #count{ X: in(X), abs_map(X,X')}.

:- in(X), abs_map(X,X'), not abs_in(X').

Let's refer to these two constraints as

Finally, we need to constrain the search to clustered extensions that map to

If there are no answer sets, then no

To see examples of this, investigate and run 2-is-extension-spurious.sh.

Given some

The above procedure can be extended to achieve this by looping though the clustered extensions:

for

$\hat E \in \mathcal {AS} ( \pi_F \cup \pi_m \cup \pi_{m(F)} \cup \pi_{\hat \sigma} )$ :

$Q \leftarrow \mathcal {AS} ( \pi_F \cup \pi_m \cup \pi_{m(F)} \cup \pi_\sigma \cup \pi_{\hat \sigma} \cup \pi_{m(X) = \hat X} \cup \pi_{\hat E} )$ if

$Q = \emptyset$ return "spurious!"return "not spurious!"

This was implemented as a python program using clingo as answer set solver.

The code can be found in find_spurious.py.

Note that the procedure requires two nested calls to the clingo solver.

The outer call is for computing the clustered extensions,

the inner call to check whether that extension is spurious or not.

Note that besides

To see examples of this, investigate and run 3-find-spurious.sh

Given some

For the purposes of this project,

we settle for finding nonspurious abstraction mappings that induce a partition with minimal size

All of the following procedures start with an initial abstraction mapping

For example, in the Simonshaven AF, we may be interested in the acceptance of the argument

{a}, {b,c,d,e,f,f',g,h,i,j,k,l,aux1,aux2}

The search might yield the following partitions.

All are nonspurious and whitness the sceptical but not credulous acceptance of

{a}, {aux1}, {aux2}, {b}, {c}, {d}, {e}, {f}, {f'}, {g}, {h}, {i}, {j}, {k}, {l}

{a}, {aux1}, {aux2}, {b}, {c}, {d}, {e}, {f}, {f'}, {g,h}, {i}, {j}, {k}, {l}

{a}, {aux1,aux2,f',g}, {b,f,h}, {c,d,e,k,l}, {i,j}

{a}, {aux1,aux2,c,d,f',g,i}, {b,e,f,h}, {j,k,l}

{a}, {aux1,c,d,e,f,f',g,j,k}, {aux2,b,h,i,l}

The first procedure is inspired by the counterexample-guided abstraction refinement (CEGAR) procedure which enjoys much success in the field of model checking.

The procedure starts with

But how can we derive information from the spurious clustered extension

Finding the most similar

abs_false_positive(X') :- abs_in(X'), 0 = #count{ X: in(X), abs_map(X,X')}.

abs_false_negative(X') :- in(X), abs_map(X,X'), not abs_in(X').

:~ abs_false_negative(C). [1@2,C]

:~ abs_false_positive(C). [1@2,C]

Note that if

The clustered arguments previously identified as false positives or false negatives are prime suspects for the

occurence of

refinement_candidate(C) :- abs_false_positive(C).

refinement_candidate(C) :- abs_false_negative(C).

refinement_candidate(C) :- refinement_candidate(S), singleton(S), abs_att(C,S).

refinement_candidate(C) :- refinement_candidate(S), singleton(S), abs_att(S,C).

To refine the candidates, we generate all possible ways of splitting them into subsets. Given some clustered argument

abs_arg_size(C,S) :- abs_arg(C), S = #count{ A : abs_map(A, C) }.

1 = { abs_split(A, (C, 1..S)) } :- abs_map(A,C), refinement_candidate(C), not singleton(C), abs_arg_size(C,S).

We then constrain mappings based on the spurious extension and the found nearest classical extension.

:- abs_split(A1, C), abs_split(A2, C), in(A1), not in(A2).

:- abs_split(A1, C), abs_split(A2, C), att(A1, S), not att(A2, S), refinement_candidate(S).

:- abs_split(A1, C), abs_split(A2, C), att(S, A1), not att(S, A2), singleton(S), refinement_candidate(S).

The goal is to perform as little splitting as possible while still respecting above constraints. This preference is implemented as another weak constraint:

splits(C,M) :- M=#count { N : abs_split(_, (C,N)) }, refinement_candidate(C), not singleton(C).

:~ abs_split(A, (C,N)). [1@1,C,N]

To guarantee that at least one split happens for every refinement candidate, the following constraint can be added. So, if the above constraints do not help, we simply guess splits.

:- splits(_, M), M<=1.

Finally, we define a new mapping based on the performed splits.

abs_map_refined(A,(C,I)) :- abs_split(A,(C,I)).

abs_map_refined(A,C) :- abs_map(A,C), not abs_split(A,(C,_)).

All the above code is found in spurious-guided-refinement.lp.

In the following we refer to it as

Additionally recall the ASP encodings defined above:

-

$\pi_F = \{ \textbf{arg} (a). \mid a \in A \} \cup \{ \textbf{att} (a,b). \mid (a,b) \in R \}$ . $\pi_m = \{ \textbf{abs\_map} (a, \hat a). \mid a \in A, m(a) = \hat a \}$ -

$\pi_{m(F)}$ to deduce$\textbf{abs\_arg}/1$ ,$\textbf{singleton}/1$ and$\textbf{abs\_att}/2$ . -

$\pi_{\sigma}$ to deduce$\textbf{in}/1$ -

$\pi_{\hat \sigma}$ to deduce$\textbf{abs\_in}/1$ $\pi_{\hat E} = \{ \textbf{abs\_in}(\hat a). \mid \hat a \in \hat E \} \cup \{ \textbf{-abs\_in}(\hat a). \mid \hat a \in \hat A \setminus \hat E \}$

With this we construct the following procedure:

$m \leftarrow \text{coarse initial mapping}$ while

$\textbf{True}$ :

$refine \leftarrow \textbf{False}$ for

$\hat E \in \mathcal {AS} ( \pi_F \cup \pi_m \cup \pi_{m(F)} \cup \pi_{\hat \sigma} )$ :

$I \leftarrow$ an optimal answer set from$\mathcal {AS} ( \pi_F \cup \pi_m \cup \pi_{m(F)} \cup \pi_\sigma \cup \pi_{\hat \sigma} \cup \pi_{m(X) \sim \hat X} \cup \pi_{\hat E} )$ if

$cost(I) > 0$ :

$m \leftarrow$ extract refined mapping from$\textbf{abs\_map\_refined}/2$ predicates in$I$

$refine \leftarrow \textbf{True}$ break

if

$refine = \textbf{False}$ :break

return

$m$

Note that if the classical AF has no extensions under some semantics (e.g. Figure 3 in Saribatur and Wallner 20211), this procedure will fail. This is because abstraction depends on finding similar classical extensions. If there are none, then there are no answer sets and the refinement step is ill-defined.

The procedure is implemented in refine-spurious-guided.py.

To examples of the procedure,

run and investigate 4-refine-spurious-guided.sh as well as

4-refine-spurious-guided-tests.sh.

It was hard to assess the performance of the previous procedure without some baseline. Thus, the next step in the project was to consider an exhaustive search technique that guarantees optimality and yields ideal results for comparison.

As before, we start with an initial mapping

{ congruent(A,B) : abs_map(A,C), abs_map(B, C) }.

congruent(A,A) :- arg(A).

congruent(A,B) :- congruent(B,A).

congruent(A,C) :- congruent(A,B), congruent(B,C).

From the congruences, we can derive an abstraction mapping as follows:

1 = { abs_split(A, (C,B)) : congruent(A, B) } :- abs_map(A,C).

:- abs_split(A, (X,B)), abs_map(A,X), congruent(A,C), C<B.

To optimize for the smallest partition, every split is associated with a cost of 1.

:~ abs_split(_, (C,N)). [1,C,N]

The following procedure performs the exhaustive search.

The ASP encoding above is referred to as

$\pi \leftarrow \pi_{\text{Exhaustive}} \cup \pi_{m_0}$

$\epsilon \leftarrow \infty$ while

$\textbf{True}$ :

$I \leftarrow$ an answer set from$\mathcal {AS} (\pi)$ with optimization cost$cost(I) \leq \epsilon - 1$ if no

$I$ was found:break

$m \leftarrow$ extract the current mapping from$I$ spurious

$\leftarrow$ check whether$m$ is spurious based on previously described proceduresif spurious:

Add a constraint to

$\pi$ such that$m$ cannot occur again in the searchelse:

report

$m$ as admisible mapping

$\epsilon \leftarrow cost(I)$

In words, the procedure tries to find some admissible mapping strictly smaller than the current best admissible mapping. Already visited mappings will be marked as visited by adding them as constraints to the ASP search procedure. The procedure is done when ASP can no longer yield answer sets. Then, the current best admissible mapping is the optimal one.

The procedure is implemented in refine-exhaustive.py.

To see examples of this procedure,

investigate and run 5-refine-exhaustive.sh.

Experimental variants of the procedure were implemented as well.

- By removing the cost restriction in line 4, it is possible to enumerate all nonspurious mappings, not just the ones that are better than the current best one.

- In line 4, instead of simply finding some model of cost below the current best cost, we can enforce that the smallest unvisited mapping should always be considered next. Thus, a strict oder on enumerating mappings is enforced, from smallest to largest. This has no effect on the optimality of the procedure, but may affect performance significantly.

To see examples of these modifications, investigate and run 5-refine-exhaustive-experimental.sh.

To see a full list of command line options, run python refine-exhaustive.py -h.

One of the problems of the search guided by spurious abstraction mappings is that there is little control over the order of occurences of counterexamples and how they affect the splitting process. This makes it hard to see whether splitting process works well or not at all.

The exhaustive search technqiue works well, but searches the entire space of possible partitions, one by one. This does not scale to larter frameworks.

In this next attempt, we try to use the exhaustive search procedure as a framework, but still try to learn from spurious counterexampes and try to add learned information as nogoods. Ideally, this lets us:

- Check the quality of nogoods learned from counterexamples in an exhaustive search context.

- Significantly reduce the number of partitions to check (due to the nogoods), making the procedure viable for larger AF's.

Learning nogoods from spurious counterexamples works just as before.

The only difference is that no splitting of refinement candidates is performed.

Instead, "noncongruents" of the form

abs_false_positive(X') :- abs_in(X'), 0 = #count{ X: in(X), abs_map(X,X')}.

abs_false_negative(X') :- in(X), abs_map(X,X'), not abs_in(X').

:~ abs_false_negative(C). [1@1,C]

:~ abs_false_positive(C). [1@1,C]

refinement_candidate(C) :- abs_false_positive(C).

refinement_candidate(C) :- abs_false_negative(C).

refinement_candidate(C) :- refinement_candidate(S), singleton(S), abs_att(C,S).

refinement_candidate(C) :- refinement_candidate(S), singleton(S), abs_att(S,C).

refine(A,C) :- refinement_candidate(C), abs_map(A,C).

-congruent(A1, A2) :- refine(A1,C), refine(A2,C), in(A1), not in(A2).

-congruent(A1,A2) :- refine(A1,C), refine(A2,C), att(A1,S), not att(A2,S), refinement_candidate(S).

-congruent(A1,A2) :- refine(A1, C), refine(A2, C), att(S, A1), not att(S, A2), singleton(S), refinement_candidate(S).

Above encoding can be found in spurious-refinement-noncongruence.lp

These "noncongruents" can be added as facts to the ASP encoding that exhaustively generates new partitions, as indicated in the modified procedure below.

$\pi \leftarrow \pi_{\text{Exhaustive}} \cup \pi_{m_0}$

$\epsilon \leftarrow \infty$ while

$\textbf{True}$ :

$I \leftarrow$ an answer set from$\mathcal {AS} (\pi)$ with optimization cost$cost(I) \leq \epsilon - 1$ if no

$I$ was found:break

$m \leftarrow$ extract the current mapping from$I$ spurious, noncongruents

$\leftarrow$ check whether$m$ is spurious. If not, try to derive noncongruents based on the previously described procedure.if spurious:

Add a constraint to

$\pi$ such that$m$ cannot occur again in the searchAdd noncongruents as facts to

$\pi$ else:

report

$m$ as admisible mapping

$\epsilon \leftarrow cost(I)$

For an example of this procedure, investigate and run 5-refine-exhaustive-experimental.sh.

We test the following examples

- Fig1c: Figure 1c 1 with admissible semantics

- Fig3: Figure 3 1 with everything mapped to one and the same cluster, stable semantics

- Simonshaven: The simonshaven example from above with

$a$ singleton, everything else mapped to one and the same cluster. Admissible and stable semantics.

We test the following procedures

- Spurious-guided: Search guided by spurious abstraction mappings

- Exhaustive : Exhaustive search for the smallest abstraction

- Hybrid: The exhaustive search variant that also tries to learn nogoods

The following table shows all the run tests.

For the raw results see 4-refine-spurious-guided.sh.out, 5-refine-exhaustive.sh.out and 5-refine-exhaustive-experimental.sh.out.

Repeat the experiments for yourself by running 4-refine-spurious-guided.sh, 5-refine-exhaustive.sh and 5-refine-exhaustive-experimental.sh.

| Example | Method | Time | Best size | Best partition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fig1c, |

Spurious-guided | 5 | {a}, {b}, {c}, {d}, {e} |

|

| Fig1c, |

Exhaustive | 3 |

{a,b,c}, {d}, {e} ( = Figure 1b) |

|

| Fig3, |

Spurious-guided | NA | NA | NA |

| Fig3, |

Exhaustive | 5 |

{a,b,g,h}, {c}, {d}, {e}, {f} ( = Figure 3b) |

|

| Simonshaven, |

Spurious-guided | 9 | {a}, {aux1}, {aux2}, {b}, {c}, {d}, {e,f,f',g,h,i,k}, {j} |

|

| Simonshaven, |

Exhaustive | 3 | {a}, {aux1,c,d,e,f,f',g,j,k}, {aux2,b,h,i,l} |

|

| Simonshaven, |

Hybrid | 13 | {a}, {aux1}, {aux2}, {b}, {c}, {d}, {e,i,k}, {f}, {f'}, {g}, {h}, {j}, {l} |

|

| Simonshaven, |

Spurious-guided | 15 | {a}, {aux1}, {aux2}, {b}, {c}, {d}, {e}, {f}, {f'}, {g}, |

|

| Simonshaven, |

Exhaustive | 4 | {a}, {aux1,aux2,b,c,d,e,f,f',i,j,k,l}, {g}, {h} |

The spurious-guided approach is very fast but in general does not yield desirable results. The exhaustive search yields good results in reasonable time, at least for the small examples considered here. The hybrid approach for the Simonshaven example under admissible semantics took longer than the exhaustive search and delivered a nondesirable result.

The search guided by spurious abstraction mappings worked in principle but did not deliver satisfactory abstractions. The first issue is that there is little control over which spurious clustered extensions and which clostest-matching classical extensions are chosen by clingo. This needs to be considered when aiming for any sort of optimality. Second, the theoretical properties of the procedure need to be considered more closely. The procedure terminated for every tested input, but formal termination remains to be shown. The constraints involved in the splitting of refinement candidates need serious reconsideration. One open question here is whether different semantics would require different constraints.

The exhaustive search technqiue worked well for the given examples but will not scale to large AFs. One possible way to solve the scaleability issue is to prune the space of abstraction mappings as shown in the hybrid methods. Also here, the method of generating nogoods needs to be reconsidered.

Also, the exhaustive search method may be improved in future work by optimizing not for the size of

Footnotes

-

Saribatur, Z. G., & Wallner, J. P. (2021, September). Existential Abstraction on Argumentation Frameworks via Clustering. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Principles of Knowledge Representation and Reasoning (Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 549-559). https://proceedings.kr.org/2021/52/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9

-

Prakken, H. (2020). An argumentation‐based analysis of the Simonshaven case. Topics in cognitive science, 12(4), 1068-1091. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tops.12418 ↩

-

Dvořák, W., König, M., Rapberger, A., Wallner, J. P., & Woltran, S. (2021). ASPARTIX-V - A Solver for Argumentation Tasks Using ASP. https://www.dbai.tuwien.ac.at/research/argumentation/aspartix/papers/ASPOCP_2021.pdf ↩ ↩2