-

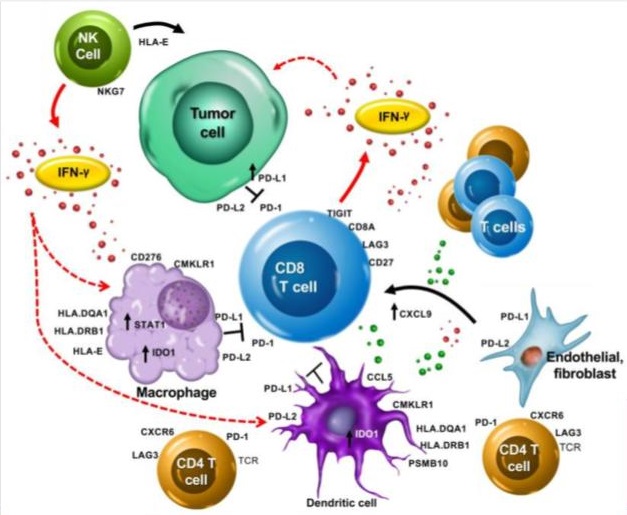

Checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy is a form of cancer treatment that blocks specific proteins on immune cells or cancer cells, known as immune checkpoints. These checkpoints act as brakes to dampen the immune system's response to cancer. By using antibodies or other agents to inhibit these checkpoint proteins, these drugs release the brakes on the immune system, enhancing its ability to recognize and attack cancer cells. Key checkpoint proteins targeted by these drugs include PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4. Blocking these pathways augments anti-tumor immunity, leading to durable clinical responses in some patients. Checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and ipilimumab have demonstrated efficacy against melanoma, lung cancer, and other malignancies. However, only a subset of patients respond, highlighting the need for biomarkers to guide patient selection.Ongoing research aims to expand the utility of checkpoint blockade across cancer types and improve patient outcomes through combination therapies.

-

Despite promising results, only a small proportion of patients with advanced cancer respond favorably to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. The majority of patients undergo unnecessary exposure to expensive yet ineffective drugs with potentially toxic side effects. The medical community is actively investigating biomarkers that can reliably predict patient responsiveness to these biological therapies. To date, the only FDA-approved predictor is PD-L1 expression measured by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Another emerging IHC-based test is ImmunoScore, which quantifies immune cell densities within the tumor microenvironment. Additional biomarkers under investigation include mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency, microsatellite instability (MSI), and tumor mutational burden (TMB). Though these tests show early promise, larger validation studies are needed to confirm their utility for response prediction and guide more personalized, precise use of checkpoint blockade therapy.

-

In this project, my partner and I researched a biomarker called TIS - Tumor Inflammation Signature.

- Developed by Ayers et. al. (2017) - IFN-Gamma-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. https://www.jci.org/articles/view/91190

- Formula made of RNA expression of 18 genes (Antigen presentation, chemokine expression, cytotoxic activity, adaptive immune resistance, interferon gamma activity)

- PSMB10, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DRB1, CMKLR1, HLA-E, NKG7, CD8A, CCL5, CXCL9, CD27, CXCR6, IDO1, STAT1, TIGIT, LAG3, CD274, PDCD1LG2, CD276

- High score should indicate success of using Pembrolizumab.

- TCGA was a landmark cancer genomic program led by the National Cancer Institute and National Human Genome Research Institute from 2006-2015.

- It systematically mapped the genomic changes in over 20,000 primary cancer samples across 33 tumor types.

- TCGA performed integrated multi-dimensional analysis including whole exome sequencing, copy number, methylation, expression analysis and proteomics on each sample.

- All TCGA data is freely available through the Genomic Data Commons portal and has led to many insights into cancer biology and precision medicine.

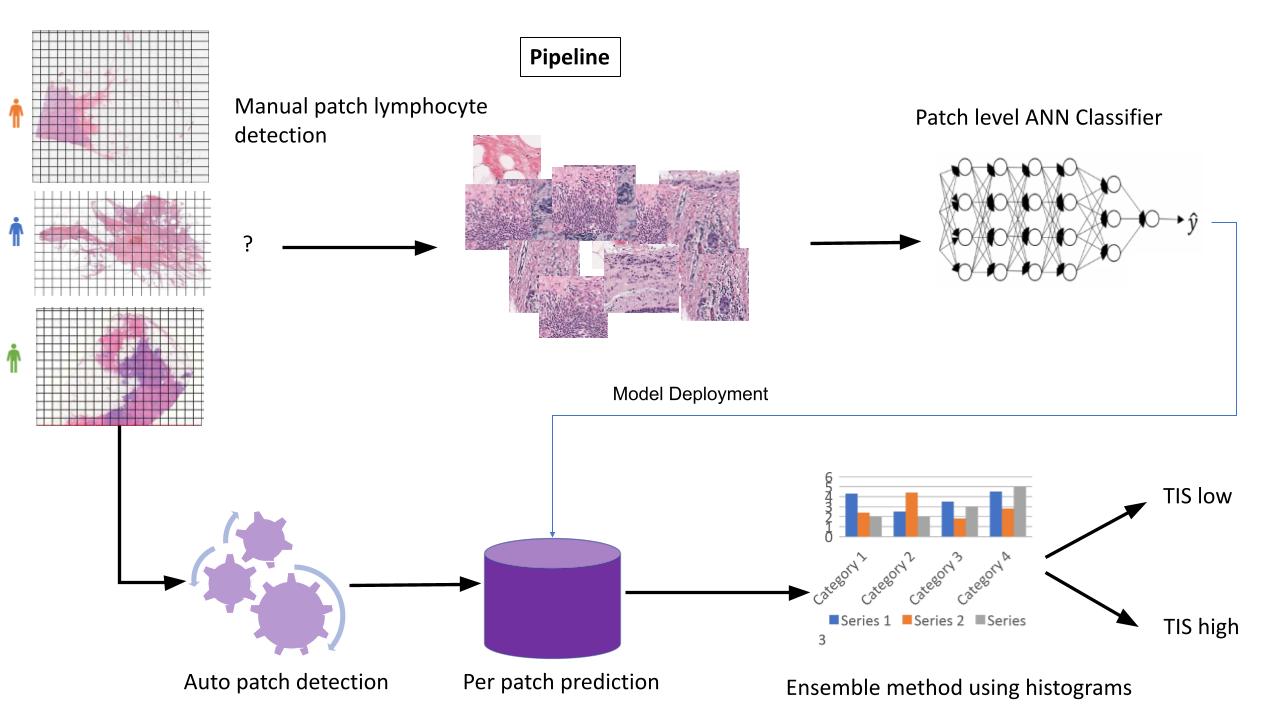

- Our idea is to use the TCGA high resolution SVS images of BRCA patients, together with their genomic data, and using deep neural network to try predicting their TIS values.

- The main problem when working with high resolution biopsies data of this kind, is how to handle the size of the image. SVS image can be as large as 3 Giga bytes, and it does not fit the current architectures of neural networks. What all researchers do is split the images to areas of interest (aoi) in the image, usually these are areas where there are lots of lymphocytes, or where the tumor is located, and train the neural net only on these areas, or patches. Finally, another model is trained in order to combine the results of all the different patches. Along the years various architectures have been developed around these two different models, the classifier and the combiner.

- The first step is downloading the SVS image files from TCGA. This cane be done using the gdc-client.exe tool and the manifest file (see the code folder).

- Next, our supervisor Professor Efroni connected us with one of his colleagues, a researcher from Ichilov Hospital, who was able to provide us access to a professional pathologist. With her guidance, we trained a group of students to mark and label regions of interest across the SVS slides in our breast cancer dataset. This allowed us to generate a large labeled training set to develop our deep learning model. The pathologist helped identify clinically relevant areas and key features for the students to focus on during the annotation process. By leveraging the pathologist's expertise, we ensured our training data had accurate, high-quality labels across numerous whole slide images. This critical preparation enabled us to apply deep learning to analyze the complex histology patterns in our unique biopsy dataset from breast cancer patients.

- After the labeling process, the next step was to split the large SVS files into smaller image patches based on the students' markings. We also performed some image preprocessing on the patches, including color correction, blurring, and other transformations. This was implemented in the image_processing.py script. Preprocessing the image patches was an important step to normalize the appearance of the histology slides and prepare the data for model training.

- The final component was training a model to aggregate the patch-level predictions into an overall slide-level output. For this combiner model, we used a tabular learner from the fastai library. The input to this model was the distribution of TIS scores predicted by the CNN for each patch across a whole slide image. The combiner model learned to analyze the shape of this score distribution to arrive at a final slide-level prediction. By training the tabular learner on top of the CNN patch classifier, we could effectively integrate the histological patterns detected across an entire SVS slide. This two-step process - first extracting features from image patches, then contextualizing the outputs for the whole slide - enabled robust computational pathology predictions from our breast cancer biopsy data. The combiner model tied together the patch classification results into a biologically coherent outcome for each patient sample.

- The best AUC we achieved was around 0.71.

- Resnet 34 with transfer learning (file tis-resnet34-histogram-tabular.py).

- Stain normalization: Implementation of a few common stain normalization techniques: (Reinhard, Macenko, Vahadane) in Python (3.5). See code\Stain_Normalization folder.

- Many PyTorch transformers (file tis-transformers.py).

- Plain PyTorch (file tis-torch.py).

- Keras (file tis-keras.py).

- Splitting model to head and body instead of trasnfer learning (file tis-split-model-to-head-and-body.py).

Our supervisor, Professor Efroni, suggested utilizing nuclear segmentation masks generated by Professor Le Hou's research group at Stony Brook University. These masks were produced as part of their study, "Dataset of Segmented Nuclei in Hematoxylin and Eosin Stained Histopathology Images of Ten Cancer Types," and are freely available on their GitHub repository (https://github.com/SBU-BMI/quip_cnn_segmentation). The masks delineate individual nuclei in histology images across several cancer types.

By overlaying these nuclear masks on our breast cancer biopsy slides, we could incorporate spatial lymphocyte distribution as an additional predictive feature for our TIS regression model. We hypothesized that the spatial patterns of immune infiltration may further improve performance over our previous model using patch-level histology features alone. After downloading the publicly available nuclear masks, we re-trained our regressor on this enhanced feature set. Preliminary results suggest integrating spatial context from cell segmentation masks can boost model accuracy, capturing meaningful immune geography patterns correlated with TIS scores. This approach exemplifies how integrating multi-modal datasets and domain knowledge, in this case about tumor immunology, can drive continued gains for computational pathology.